2024 brought us a total eclipse of the Sun, superb auroras, and a naked-eye comet, three top highlights of a wonderful year of celestial attractions. Maybe the best!

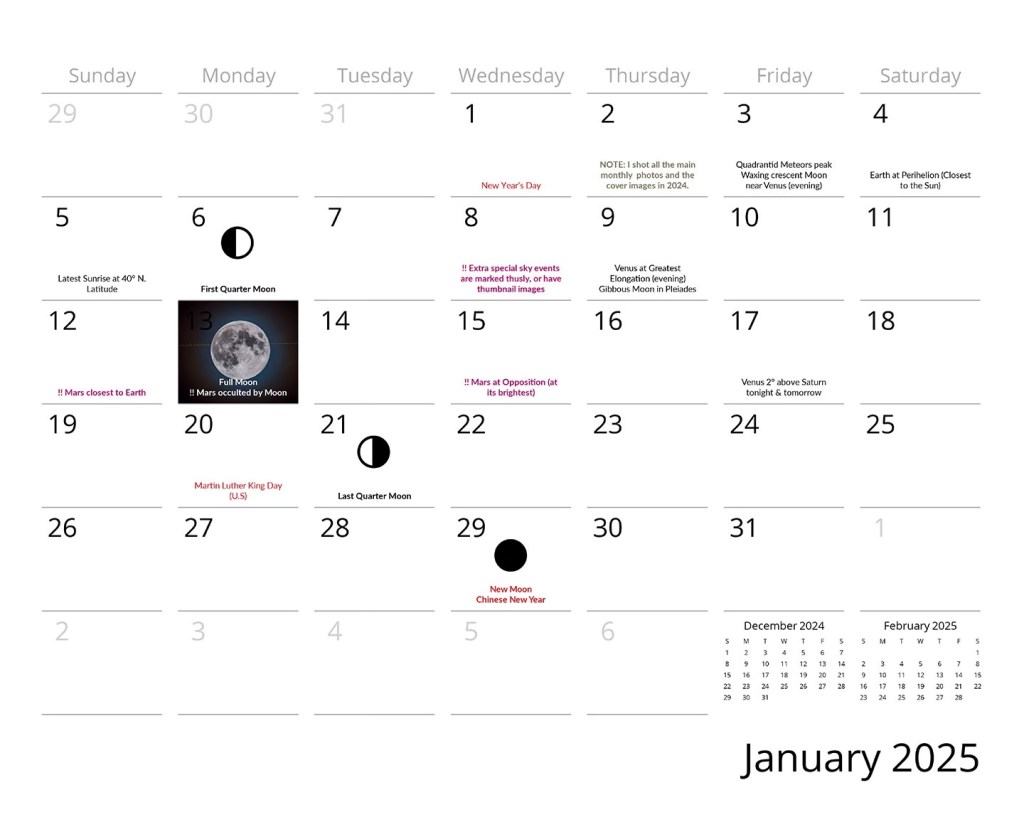

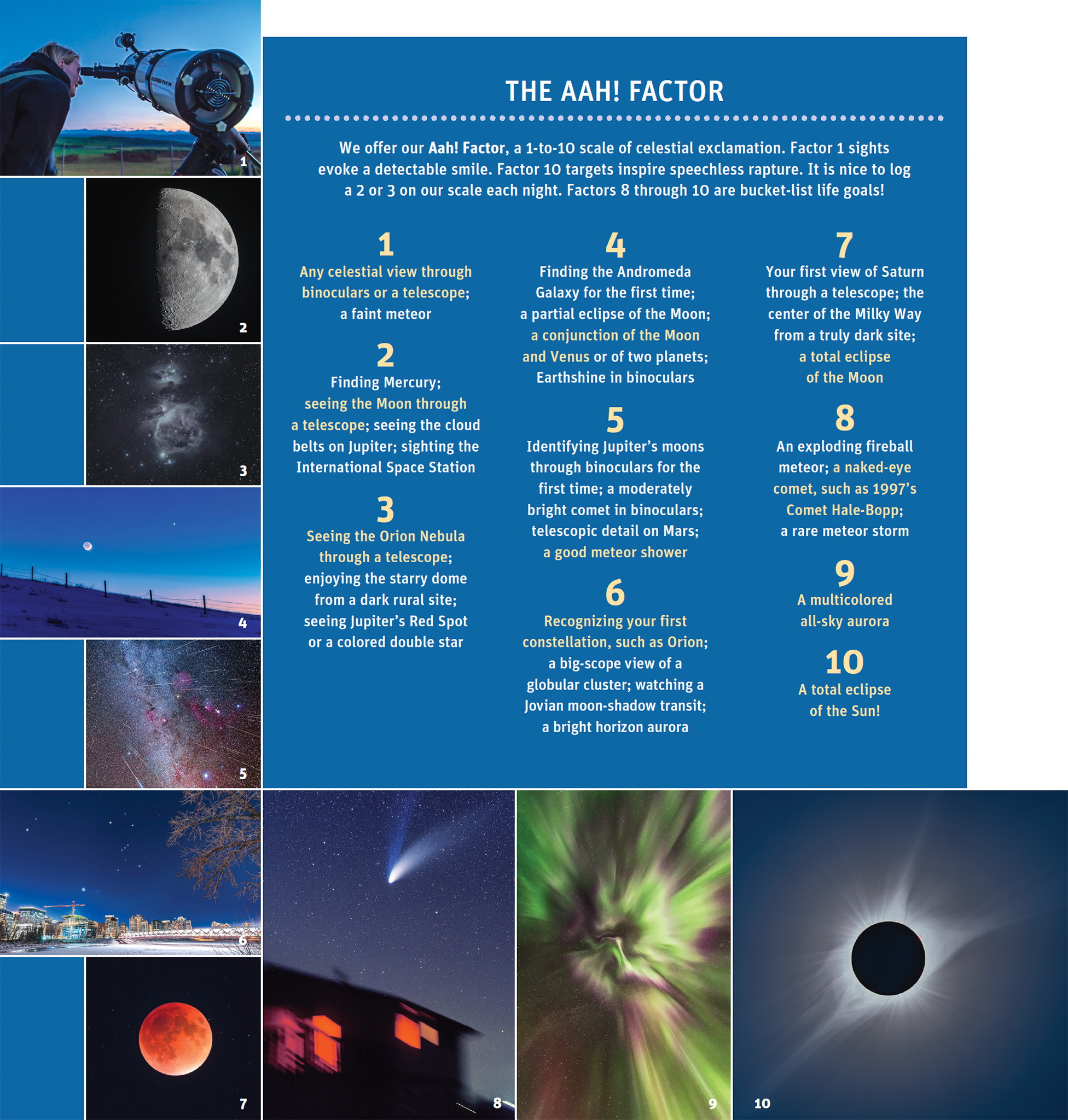

In our book The Backyard Astronomer’s Guide (which we revised this year), Terence Dickinson and I created an Aah! Factor scale with various celestial sights ranked from:

• 1, evoking just a smile, to …

• 10, a life-changing event!

Coming in at an 8 is a naked-eye comet. Deserving a 9 is an all-sky display of an aurora. The only sight to rate a top 10 is a total eclipse of the Sun.

2024 brought all three, and more!

Here’s my look back at what I think was one of the greatest years of stargazing.

NOTE: The images might take a while to all load. All can be enlarged to full screen. Just click or tap on them.

January

A Winter Moonrise to Begin the Year

Now, this was not any form of rare event. But seeing and shooting any sky sight in the middle of a Canadian winter is an accomplishment. This is the rising of the Full Moon of January, popularly called the Wolf Moon, over a frozen lake near home in Alberta, Canada 🇨🇦.

It serves to bookend the collection with a Full Moon I captured eleven months later in December.

February

Auroras from Churchill, Manitoba

Had this been my only chance to see the Northern Lights fill the sky this year, I would have been happy. As we often see in Churchill, the aurora covered the sky on several nights, a common sight when you are underneath the main band of aurora borealis that arcs across the northern part of the globe.

I attended to two aurora tour groups at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre who both got good displays to check “seeing the Northern Lights” off their bucket list. Join me in 2025!

March

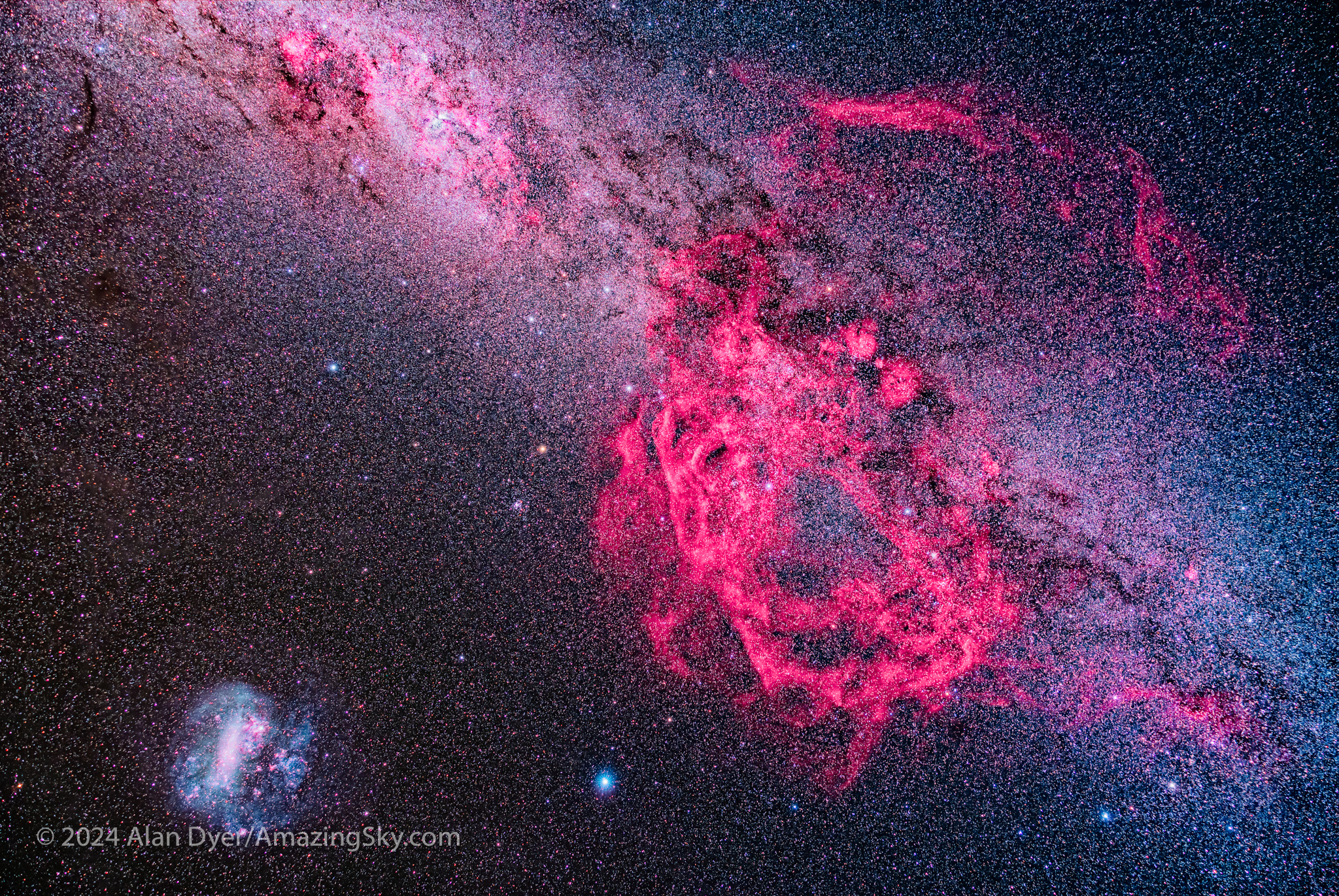

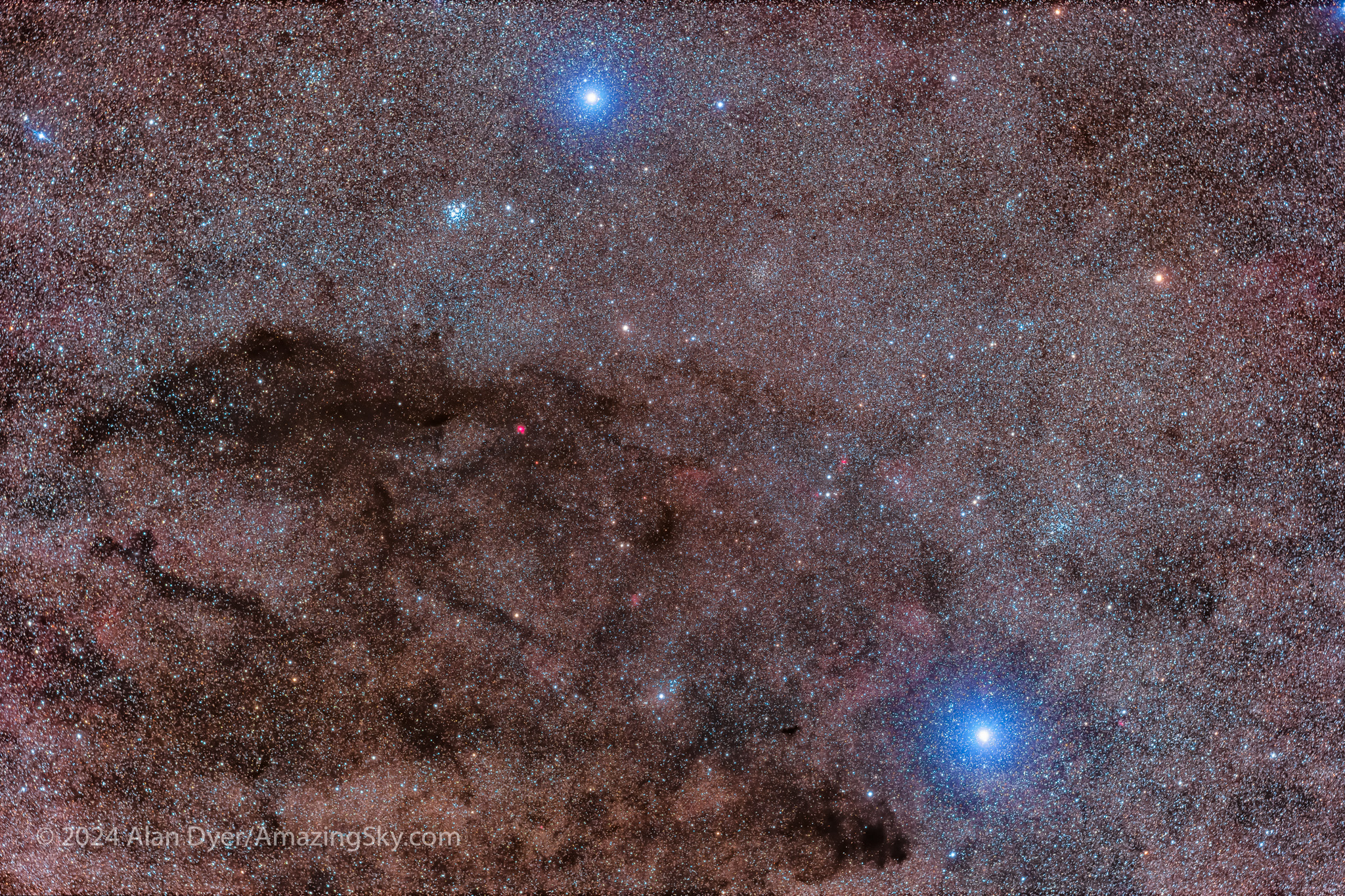

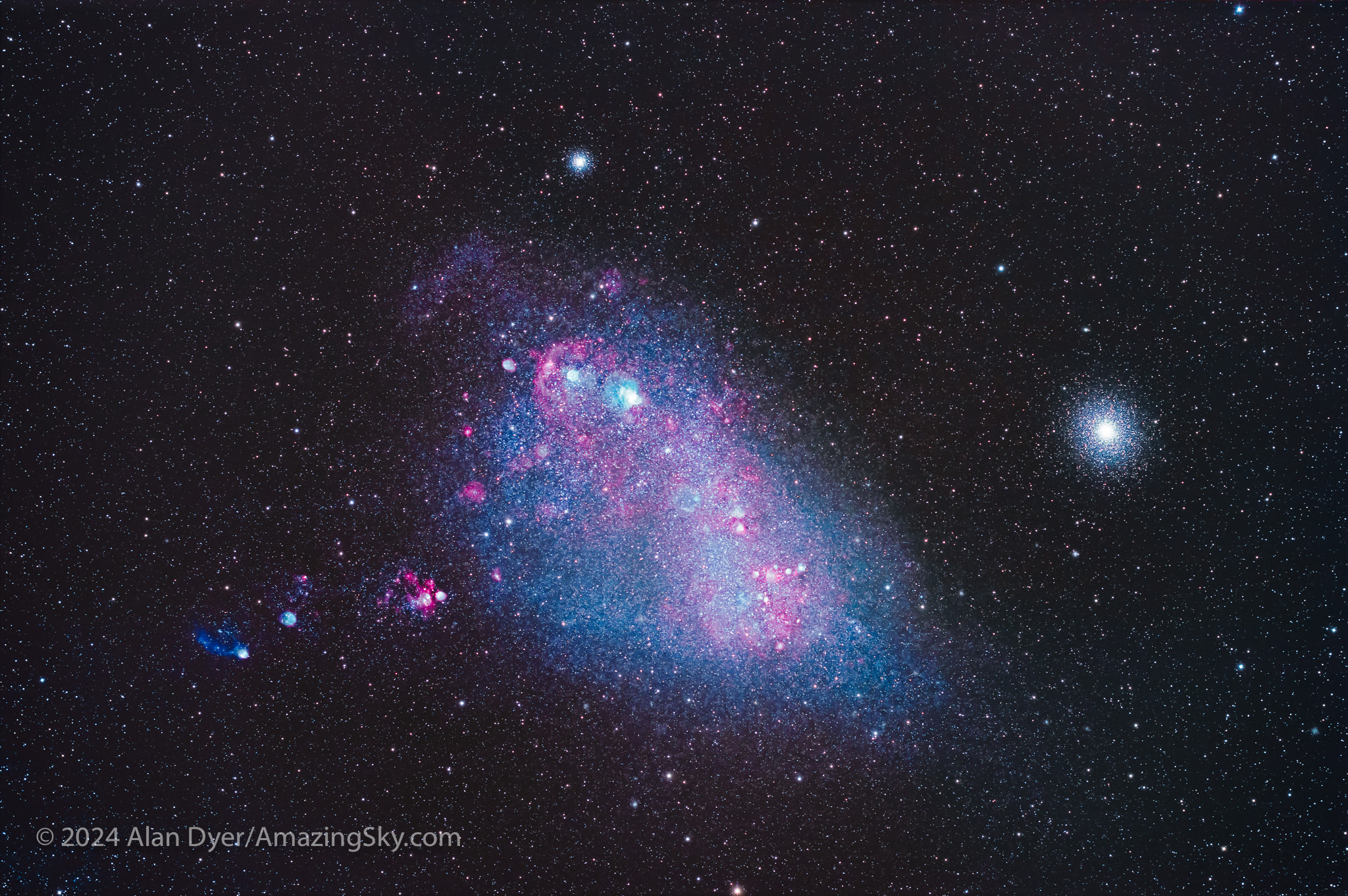

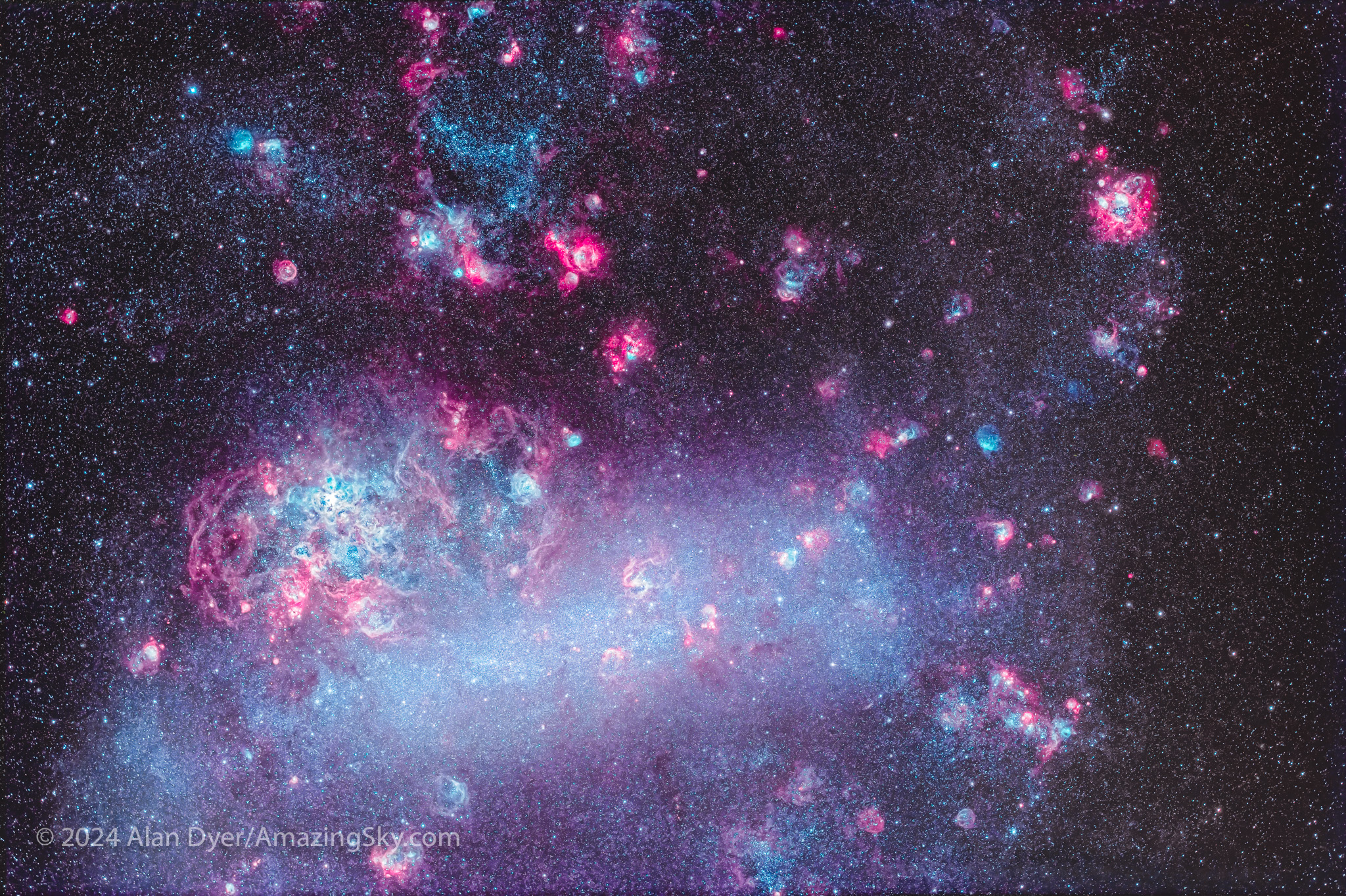

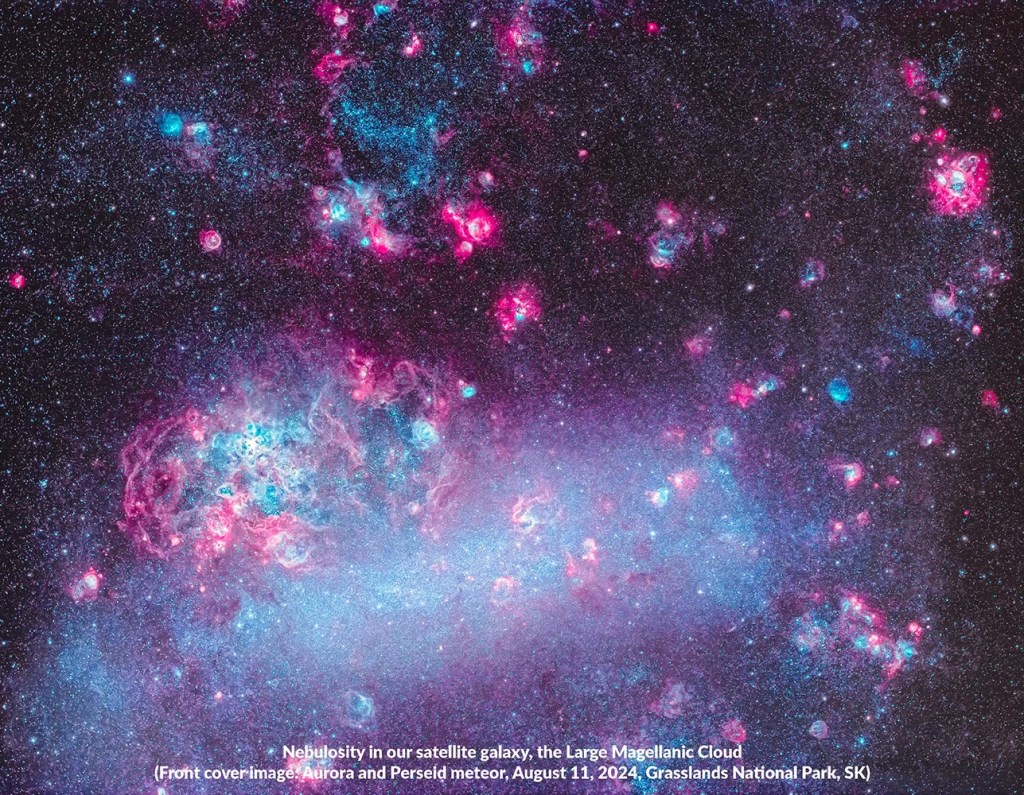

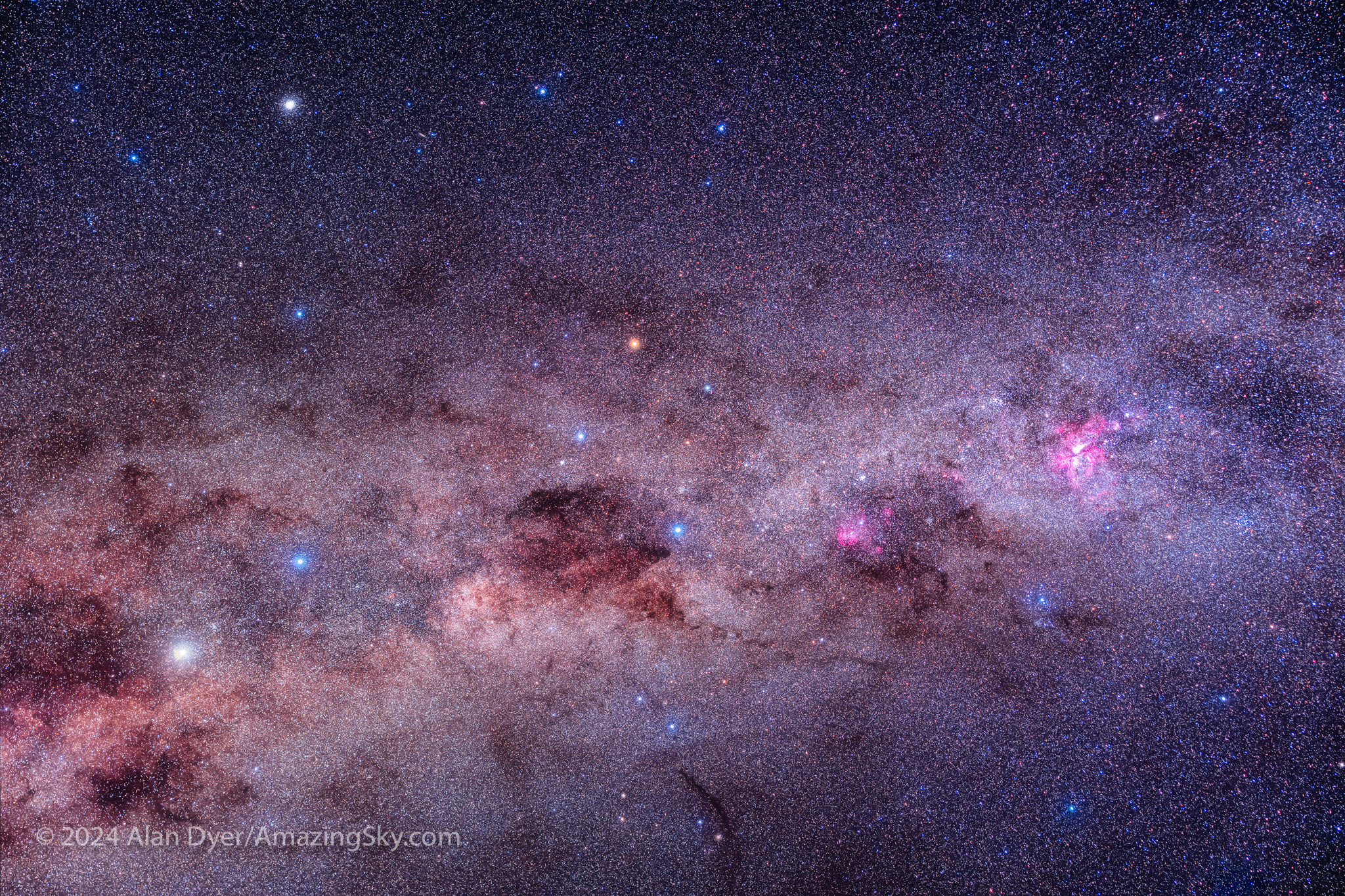

Under the Austral Sky

Ranking a respectable 7 on our Aah! Factor scale is the naked-eye sight of the galactic centre overhead, with the Milky Way arcing across the sky. That’s possible from a latitude of about 30° South. That’s where I went in March, back to Australia 🇦🇺 for the first time since 2017.

I wrote about it in my previous blog, where I present a tour along the southern Milky Way, and wide-angle views of the Milky Way (the images here are framings of choice regions).

It is a magical latitude that all northern astronomers should make a pilgrimage to, if only to just lie back and enjoy the view of our place in the outskirts of the Galaxy. I was glad to be back Down Under, to check this top sky sight off my bucket list for 2024.

April

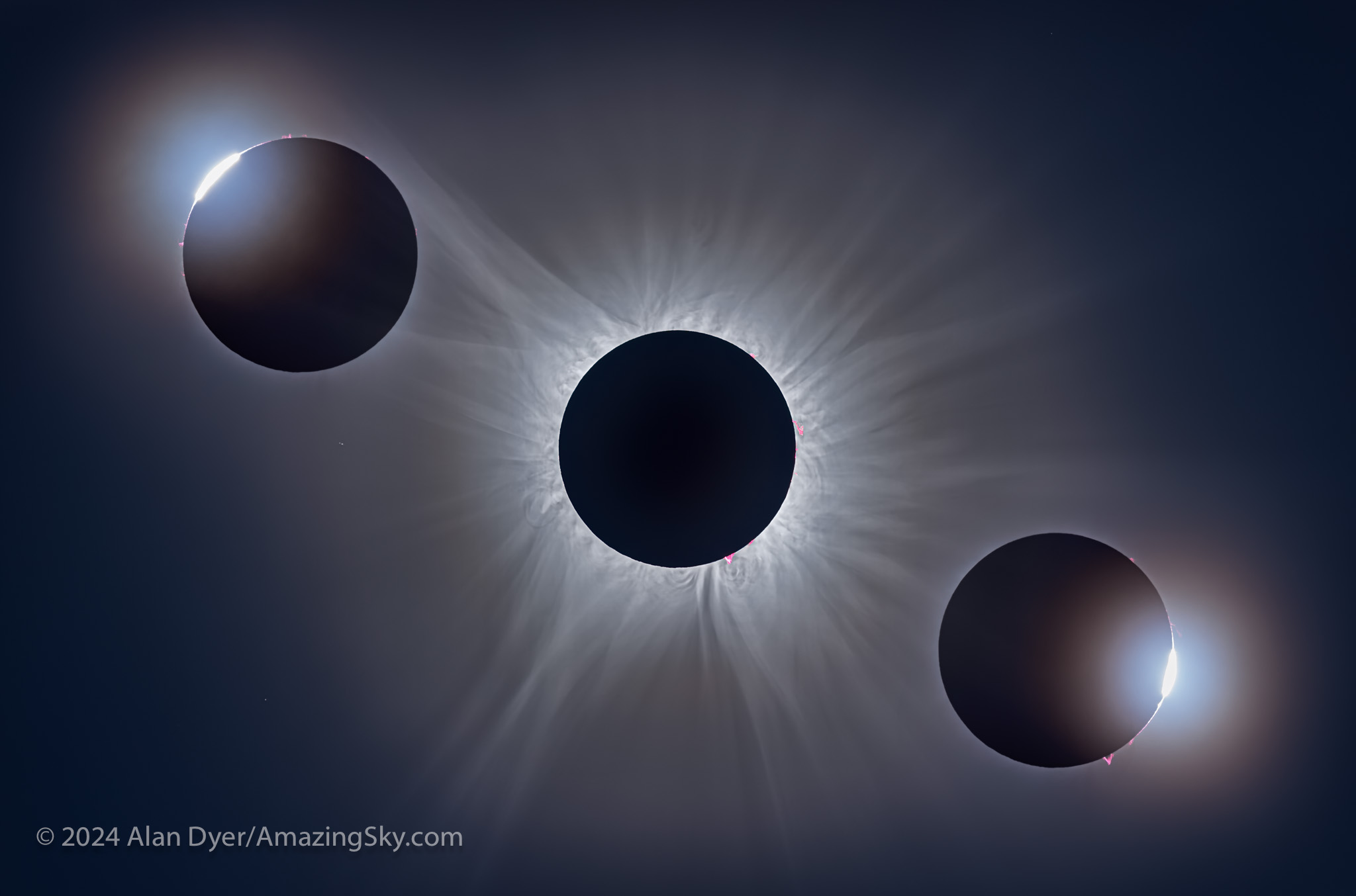

A Total Eclipse of the Sun

No sooner had I returned home from Oz, when it was time to load up the car with telescope gear and drive to the path of the April 8 total solar eclipse, the first “TSE” in North America since 2017, which was the last total eclipse I had seen, in a trip to Idaho.

But where? I started south to Texas, my Plan A. Poor weather forecasts there prompted a hasty return to Canada, to drive east across the country to … I ended up in Québec. My blog about my cross-continental chase is here. My final edited music video is linked to below.

It was gratifying to see a total eclipse from “home” in Canada, only the third time I’ve been able to do that (previously in 1979 – Manitoba, and 2008 – Nunavut). If the rest of the year had been cloudy except for this day I wouldn’t have complained. Much.

This definitely earned a 10 on the Aah! Factor scale. Total eclipses are overwhelming and addictive. I’ve made my bookings for 2026 in Spain 🇪🇸 and 2027 in Tunisia 🇹🇳.

May

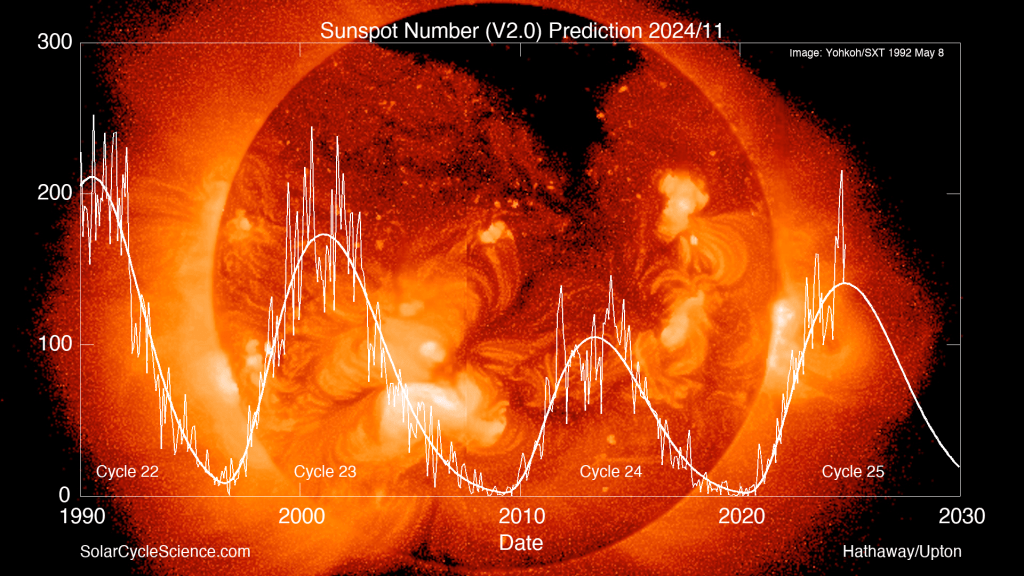

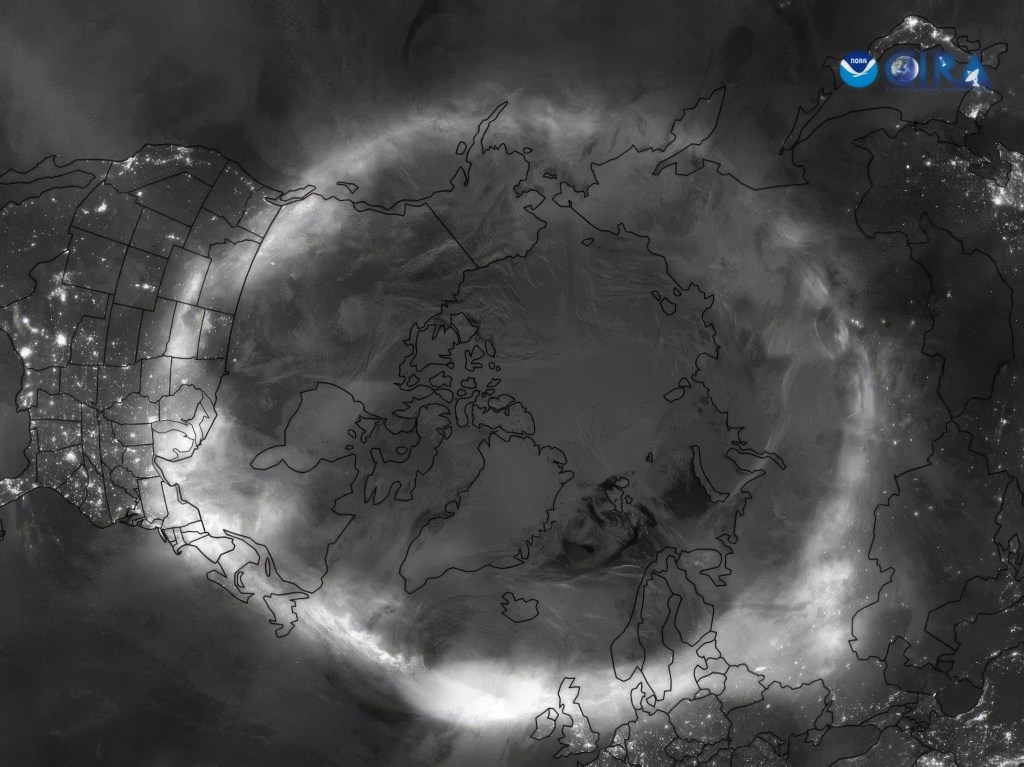

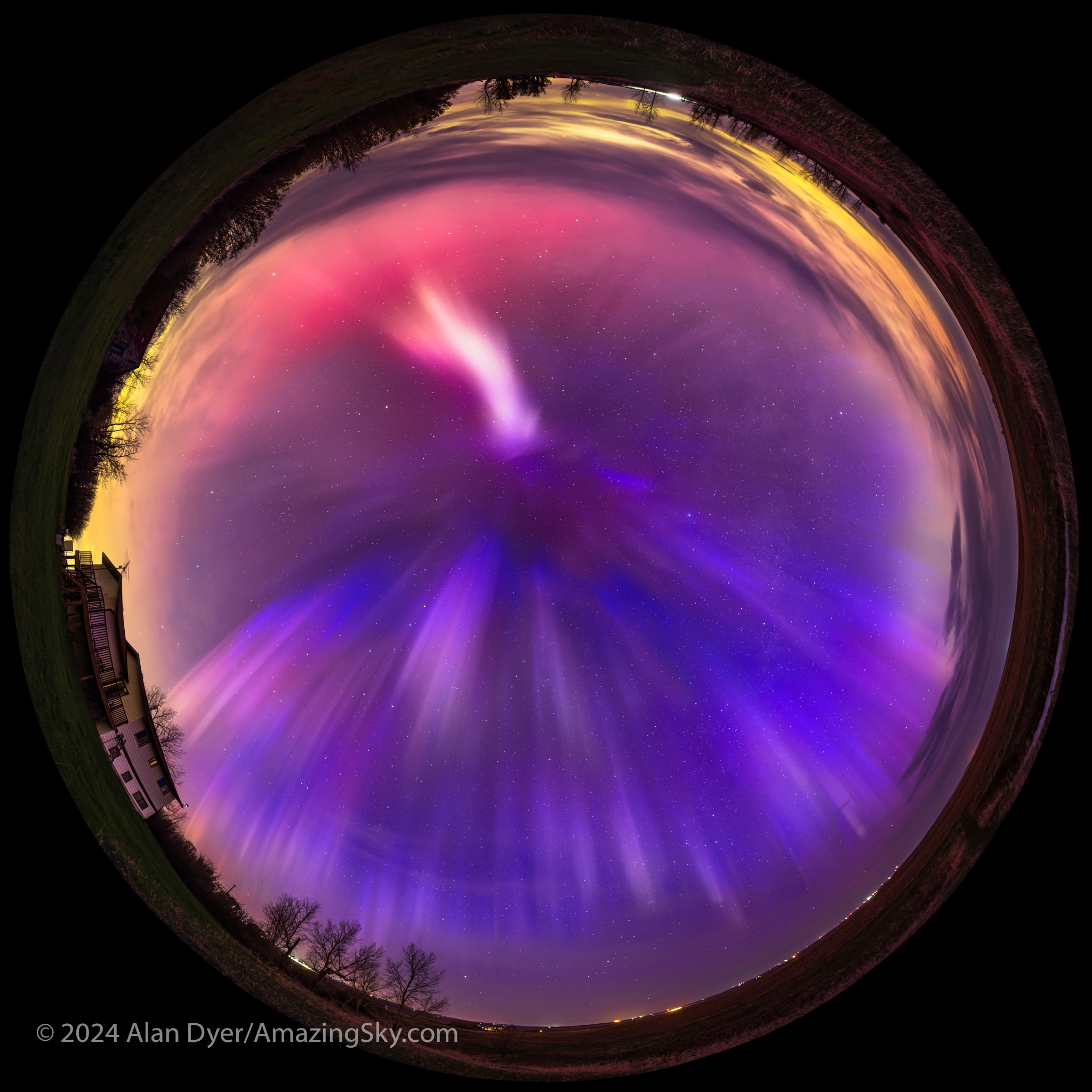

The Sky’s On Fire

It had been several years since I had seen an aurora from my backyard with colours as vivid and obvious as they were this night. But on May 10, the sky erupted with a fabulous display of aurora that much of the world saw, as aurora borealis in the north and aurora australis in the south.

This was the first of several all-sky shows this year. I blogged about the year’s great auroras here, where there are links to the movies I produced that capture the Northern Lights as only movies can, recording changes so rapid it can be hard to take it all in. Check off a 9 here!

So not even half way through the year, I had seen three of the top sky sights: the Milky Way core overhead (7), an all-sky aurora (9), and a total eclipse of the Sun (10).

But there was more to come! Including an Aah! Factor 8.

June

World Heritage Nightscape Treks

The sky took a break from presenting spectacles, allowing me to head off on short local trips, to favourite nightscape sites in southern Alberta, which we have in abundance. The Badlands of Dinosaur Provincial Park are just an hour away, the site for the scene above.

The rock formations of Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park are a bit farther, requiring a couple of days commitment to shoot. Clouds hid the main attraction, the Milky Way, this night, but did provide a fine sunset.

A little further west down the highway is Waterton Lakes National Park, another great spot I try to visit at least once each year.

All locations I hit this month are U.N. World Heritage Sites, thus the theme of my blog from June. People travel from all over the world to come here, to sites I can visit in a few hours drive.

July

Mountains by Starlight

In summer we now often contend with smoke from forest fires blanketing the sky, hiding not just the stars by night, but even the Sun by day.

But before the smoke rolled in this past summer I was able to visit a spot, Yoho National Park in British Columbia, that had been on my shot list for several years. The timing with clear nights at the right season and Moon phase has to work out. In July it did, for a shoot by starlight at Takakkaw Falls, among the tallest in Canada.

The following nights I was in Banff National Park, at familiar spots on the tourist trail, but uncrowded and quiet at night. It was a pleasure to enjoy the world-class Rocky Mountain scenery under the stars on perfect nights.

August

The All-Sky Auroras Return

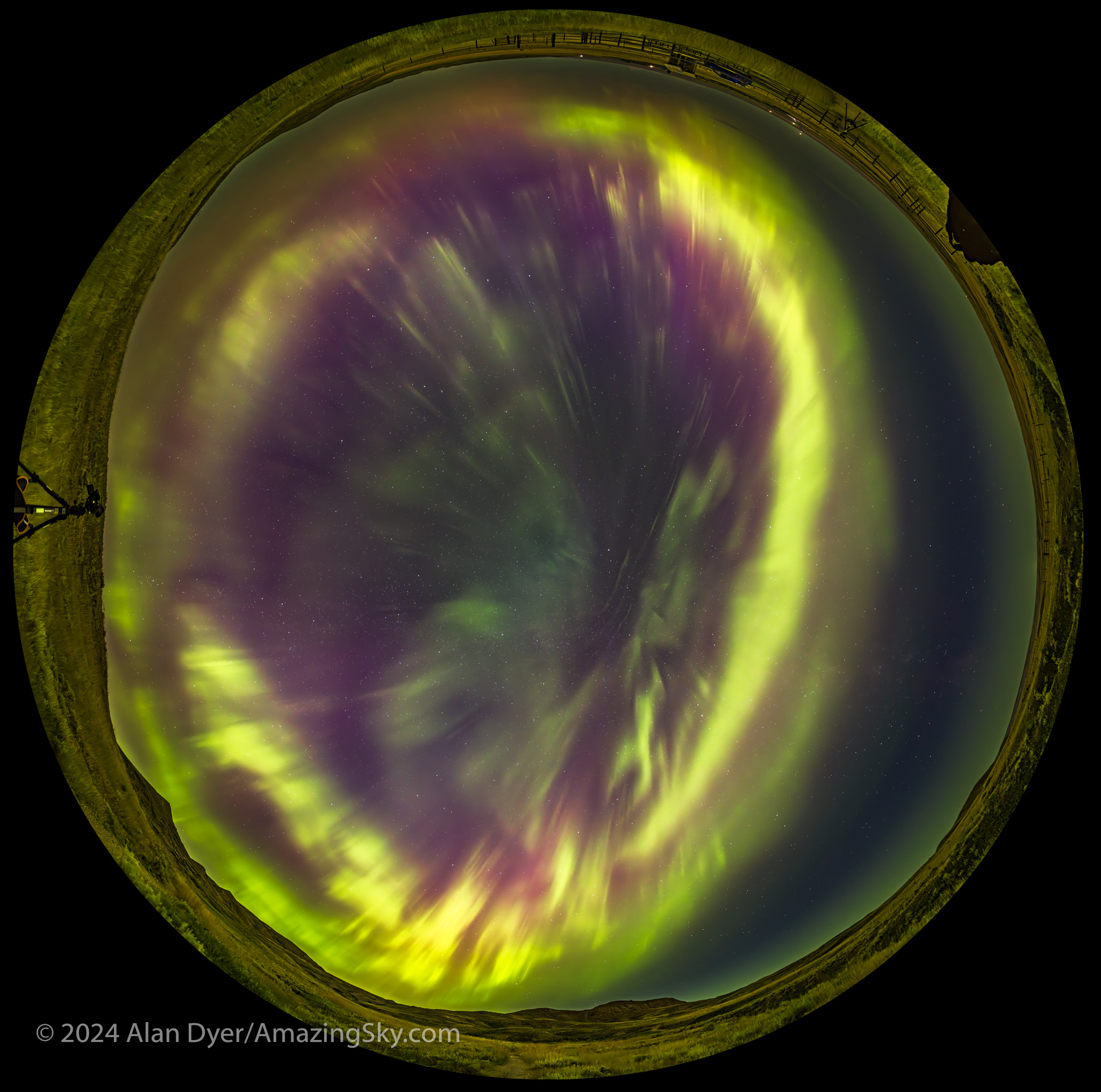

In August I headed east to Saskatchewan and the annual Summer Star Party staged by the astronomy clubs in Regina and Saskatoon. It is always a pleasure to attend the SSSP in the beautiful Cypress Hills. The sky remained clear post-party for a trip farther east to the little town of Val Marie, where I stayed at a former convent, and had a night to remember out in Grasslands National Park, one of Canada’s first, and finest, dark sky preserves.

The plan was to shoot the August 11 Perseid meteor shower, but the aurora let loose again for a stunning show over 70 Mile Butte. My earlier blog has more images and movies from this wonderful month of summertime Northern Lights.

We are fortunate in western Canada 🇨🇦 to be able to see auroras year-round, even in summer. Farther north at the usual Northern Lights destinations, the sky is too bright at night in summer.

September

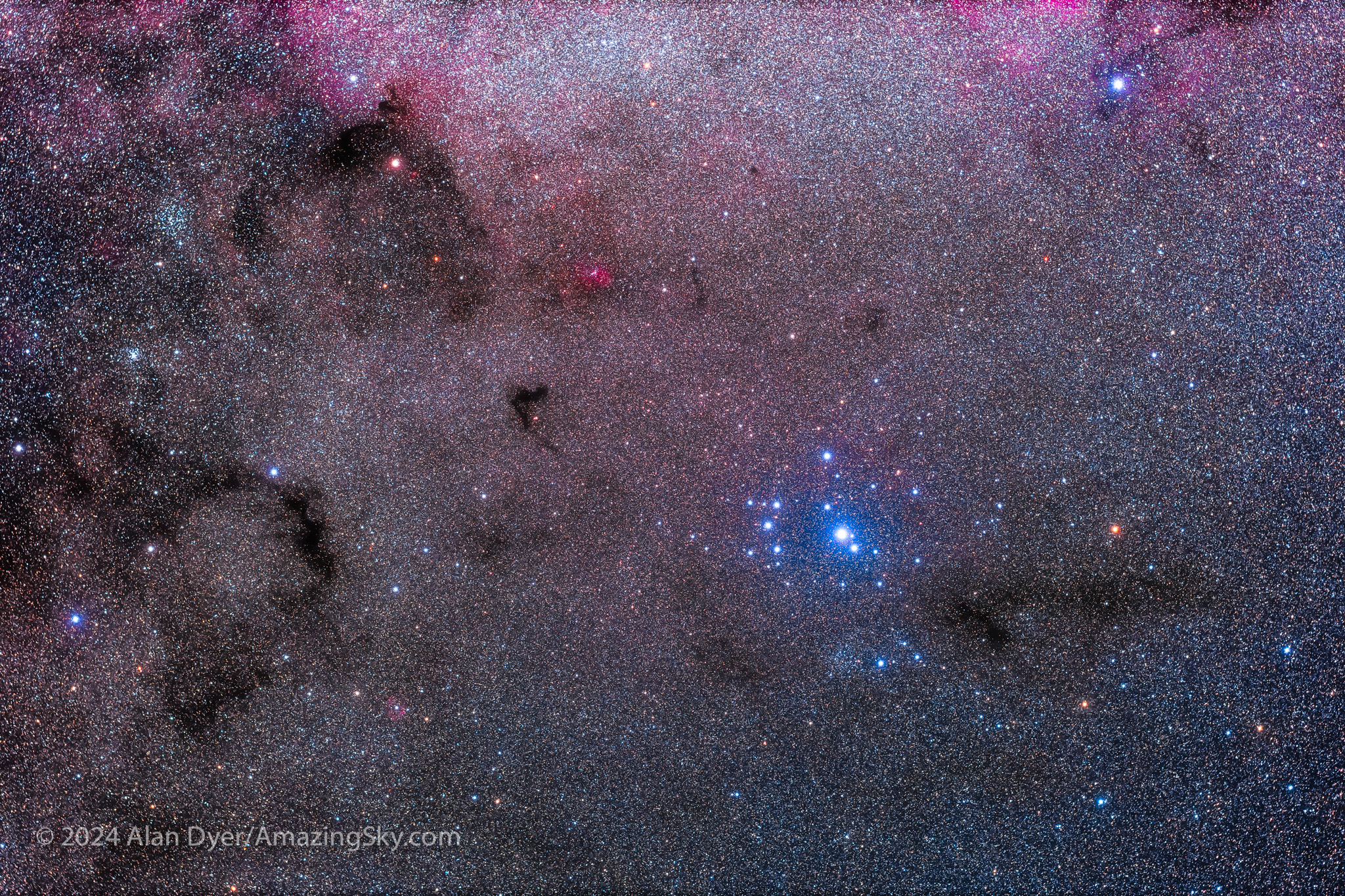

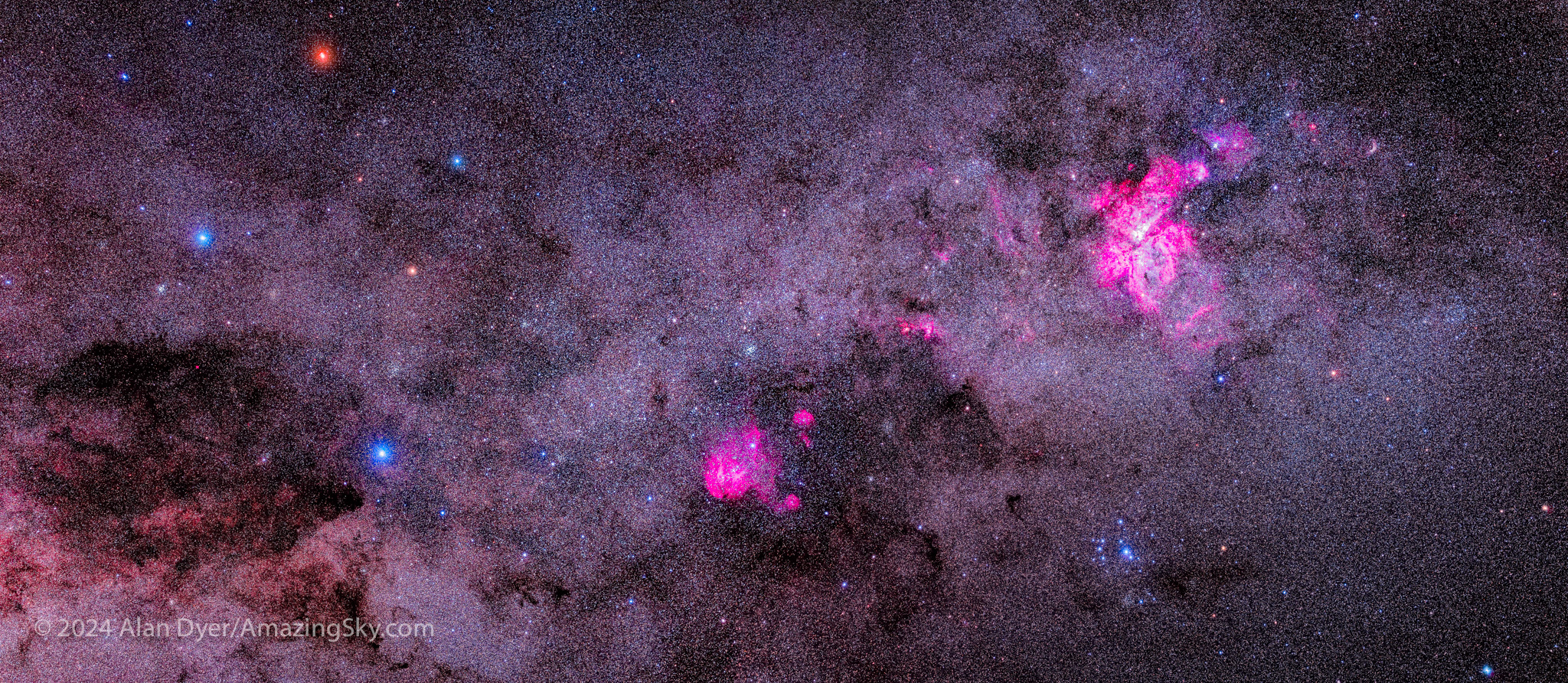

Back to Deep Sky Wonders …

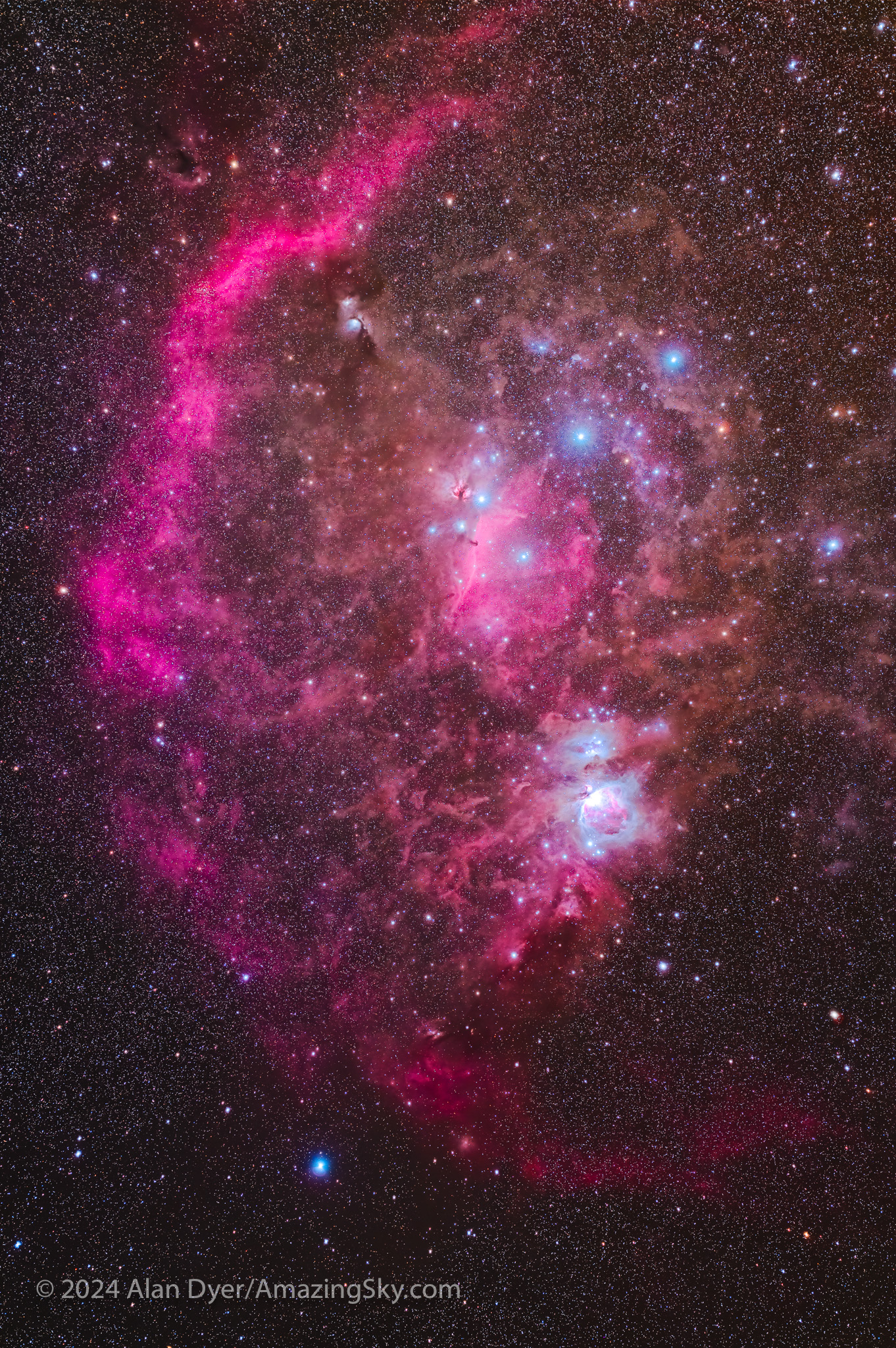

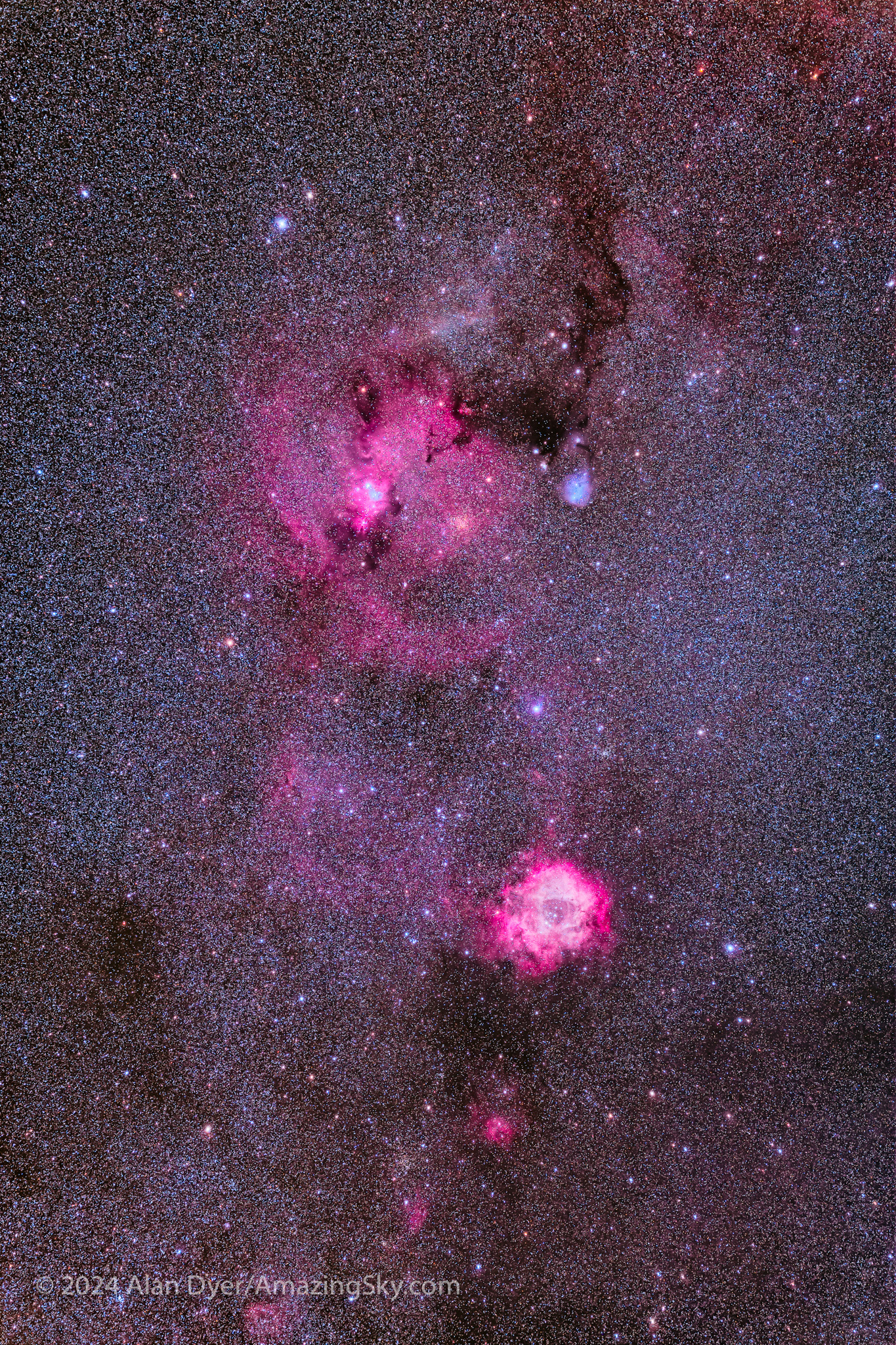

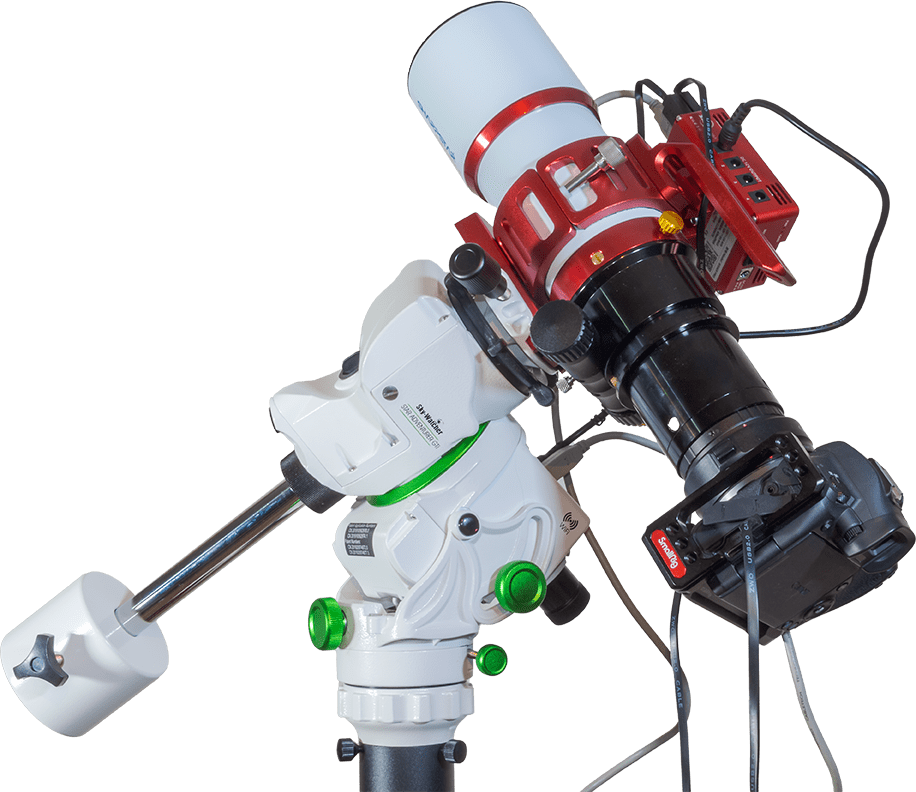

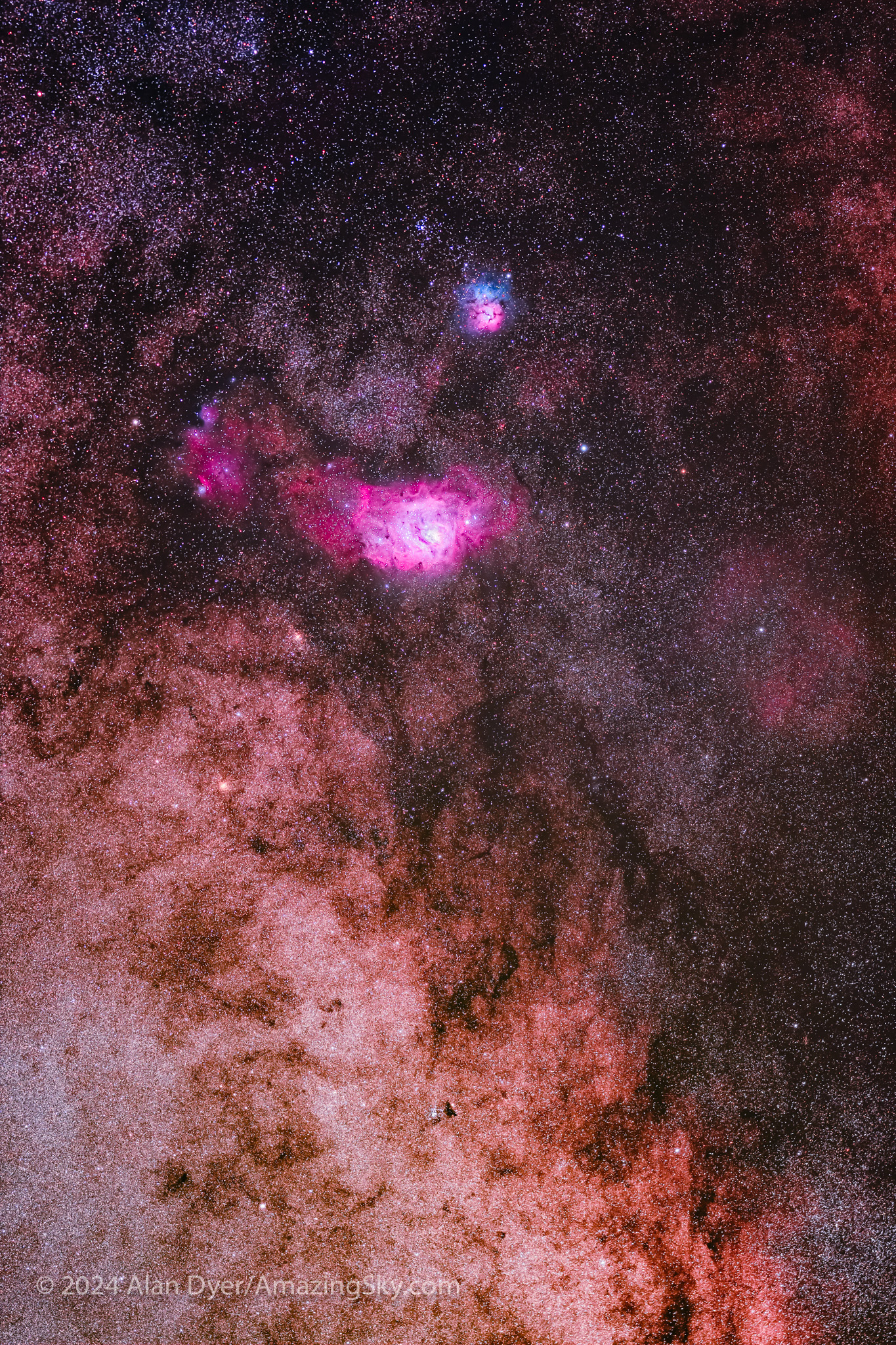

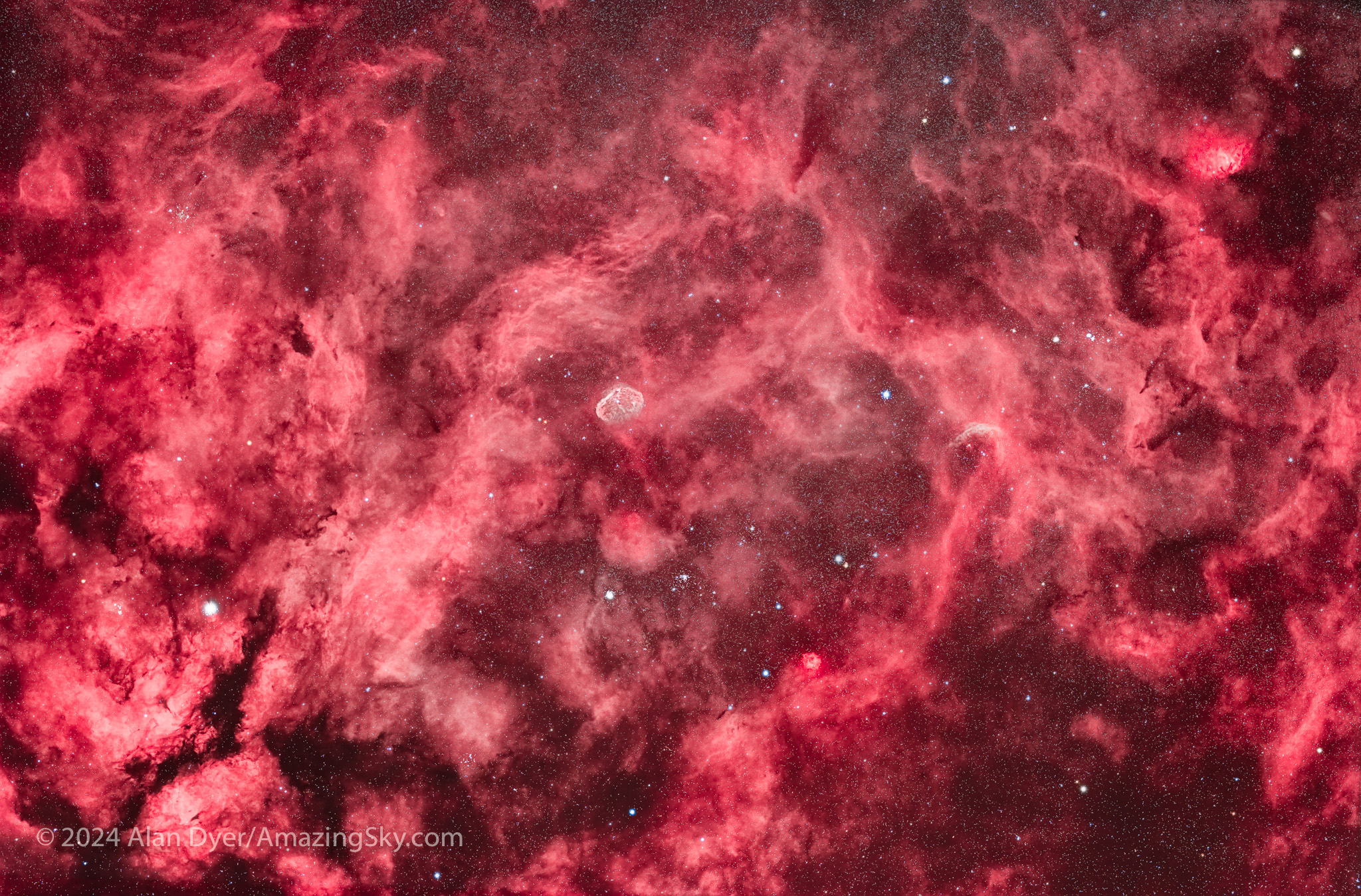

September is the month for another astronomical party in the Cypress Hills, but on the Alberta side. At the wonderful Southern Alberta Star Party under its very dark skies, I was able to shoot some favourite deep-sky fields along the Milky Way with new gear I was testing at the time.

And from home, September brought skies dark and clear enough (at least when there was no aurora!) for more captures of colourful nebulas (above and below) along the summer Milky Way.

We invest a lot of money into the kind of specialized gear needed to shoot these targets (and I’m not nearly as “committed” as some are, believe me!), only to find the nights when it all comes together can be few and far between.

… Plus, A Very Minor Eclipse of the Moon

I had to include this, if only for stark contrast with the spectacular solar eclipse six months earlier.

We had an example of the most minor of lunar eclipses on March 24, 2024, with a so-called “penumbral” eclipse of the Moon, an eclipse so slight it’s hard to tell anything unusual is happening. (So I’ve not even included an image here, though I was able to shoot it.)

On September 17, we had our second eclipse of the Moon in 2024. This time the Earth’s umbral shadow managed to take a tiny bite out of the Full Moon. Nothing spectacular to be sure. But at least this eclipse expedition was to no farther away than my rural backyard. A clear eclipse of any kind, even a partial eclipse, especially one seen from home, is reason to celebrate. I did!

Of course, a total eclipse of the Moon, when the Full Moon is completely engulfed in Earth’s umbra and turns red, is what we really want to see. They rate a 7 on our Aah! Factor scale. We haven’t had a “TLE” since November 8, 2022, blogged about here.

The next is March 14, 2025. (The link takes you to Fred Espenak’s authoritative web page.)

October

A Bright Comet At Last!

We knew early in 2024 that the then newly-discovered Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS had the potential to perform this month. I planned a trip south to favourite spots in Utah and Arizona to take advantage of what we hoped would be a fine autumn comet.

It blossomed nicely, especially as it entered into the evening sky in mid-October, as above. Despite the bright moonlight, it was easy to see with the unaided eye, a celestial rarity we get only once a decade, on average, if we are lucky. My blog of my comet chase is here.

A naked-eye comet ranks an 8 on our Aah! Factor scale. So now 2024 had delivered all four of our Top 4 sky sights.

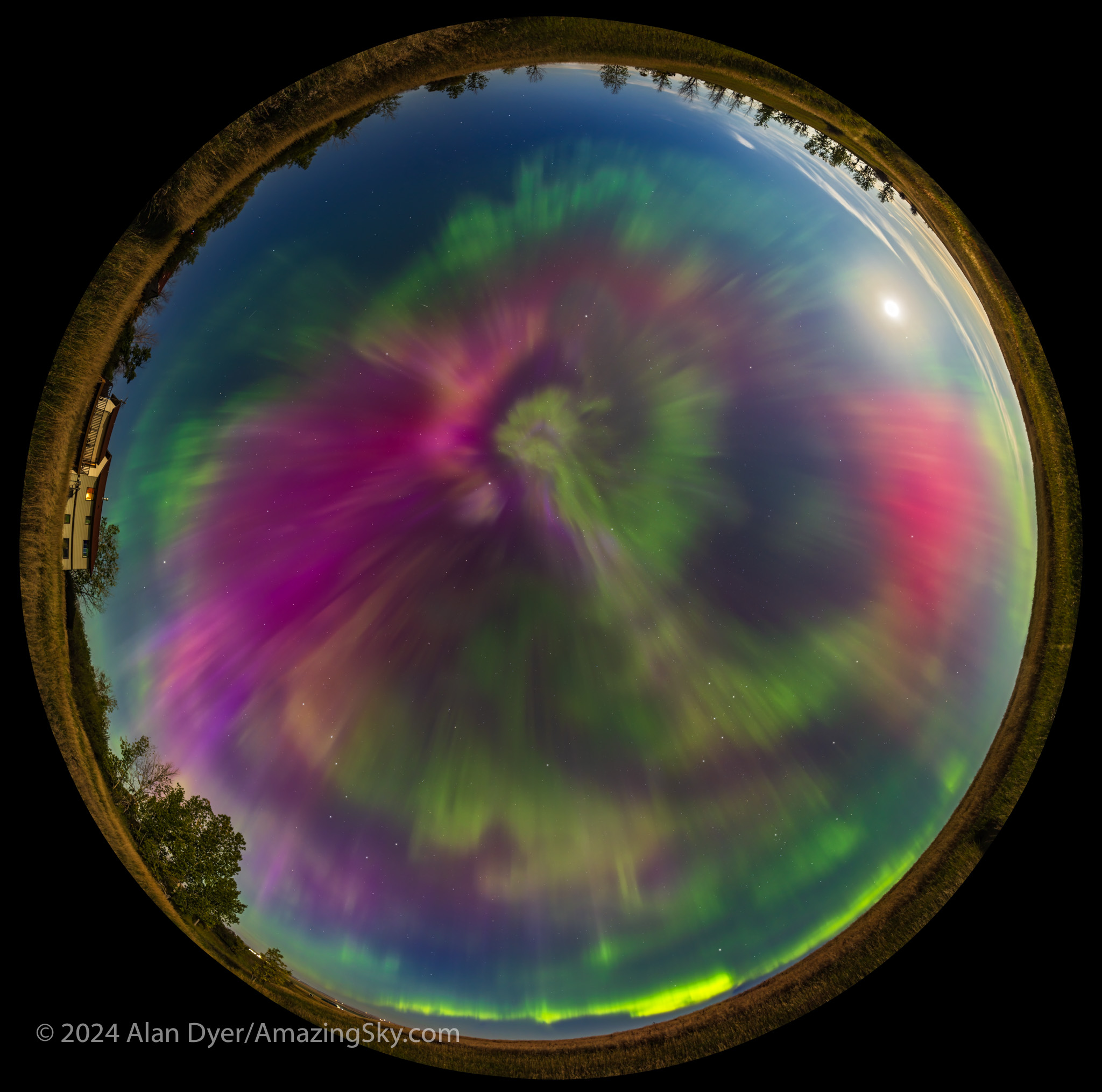

But … just as a bonus, there was another fabulous aurora on October 10, seen in my case from the unique perspective of southern Arizona, with an appearance of a bright “SAR” arc more prominent than I had ever seen before. So that view was a rarity, too, so unusual it doesn’t even make our Aah! list, as SARs are typically not visible to the eye.

November

Back to Norway for Northern Lights

2024 was notable for travel getting “back to normal,” at least for me, with two long-distance drives, and now my second overseas trip. This one took me north to Norway 🇳🇴, which I had been visiting twice a year as an enrichment lecturer during pre-pandemic years.

The auroras were excellent, though nothing like the great shows of May and October. But the location sailing along the scenic coast and fjords makes up for any shortfall in the Lights. It was good to be back. I plan to return in 2025 for two cruises in October. Join me there, too!

December

A Winter Moonrise to End the Year

As I write this, December has been nothing but cloud. Almost. A clear hour on Full Moon night allowed a capture of the “Cold Moon,” with the Moon near Jupiter, then at its brightest for the year. So that’s the other lunar bookend to the year, shot from the snowy backyard.

However, I did say after the clear total eclipse in April that if the rest of 2024 had been cloudy I wouldn’t complain. So I’m not.

And there’s no reason to, as 2024 did deliver the best year of stargazing I can remember. 2017 had a total solar eclipse. 2020 had a great comet. But we have to go back to 2003 for aurora shows as widespread and as a brilliant as we’ve seen this year. 2024 had them all. And more!

We might see more auroras in 2025. And we have a total eclipse of the Moon. Two in fact, if you’re willing to travel to the other hemisphere.

My 2025 Amazing Sky Calendar lists my picks for the best sky events of the coming year, with the emphasis on events viewable from North America. For a free PDF download of my Calendar, go to my website here.

Clear skies to all, in a Happy New Year!

— Alan, December 21, 2024 / amazingsky.com