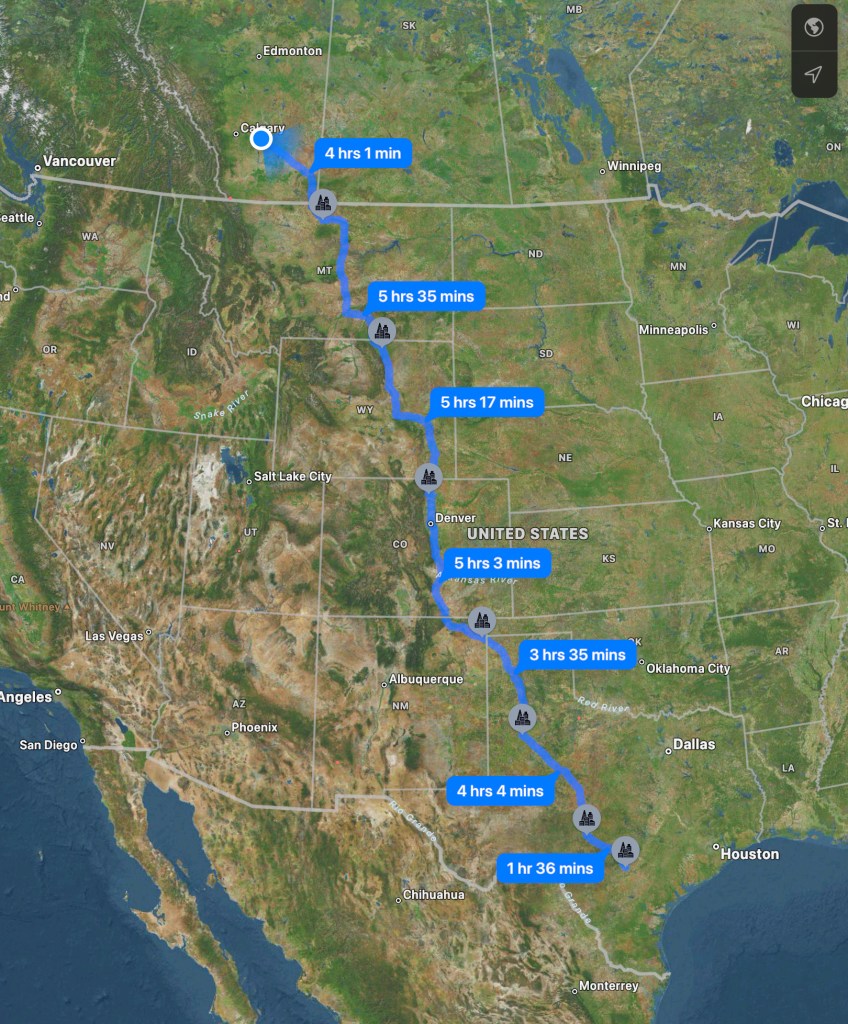

I had always planned to drive to the April 8, 2024 total eclipse of the Sun. But to where? I ended up on the other side of the continent than originally planned.

It is not often the path of the Moon’s shadow crosses your home country, let alone continent. Only once before in recent years, on August 21, 2017, did the narrow shadow path pass near enough to my home in Alberta to allow me to drive to a total eclipse. They almost always require flying.

Yes, while I could drive to the April 8, 2024 eclipse, it was going to demand a much longer drive than in 2017. But driving allowed me to take a carload of telescope and camera gear. So that was the plan.

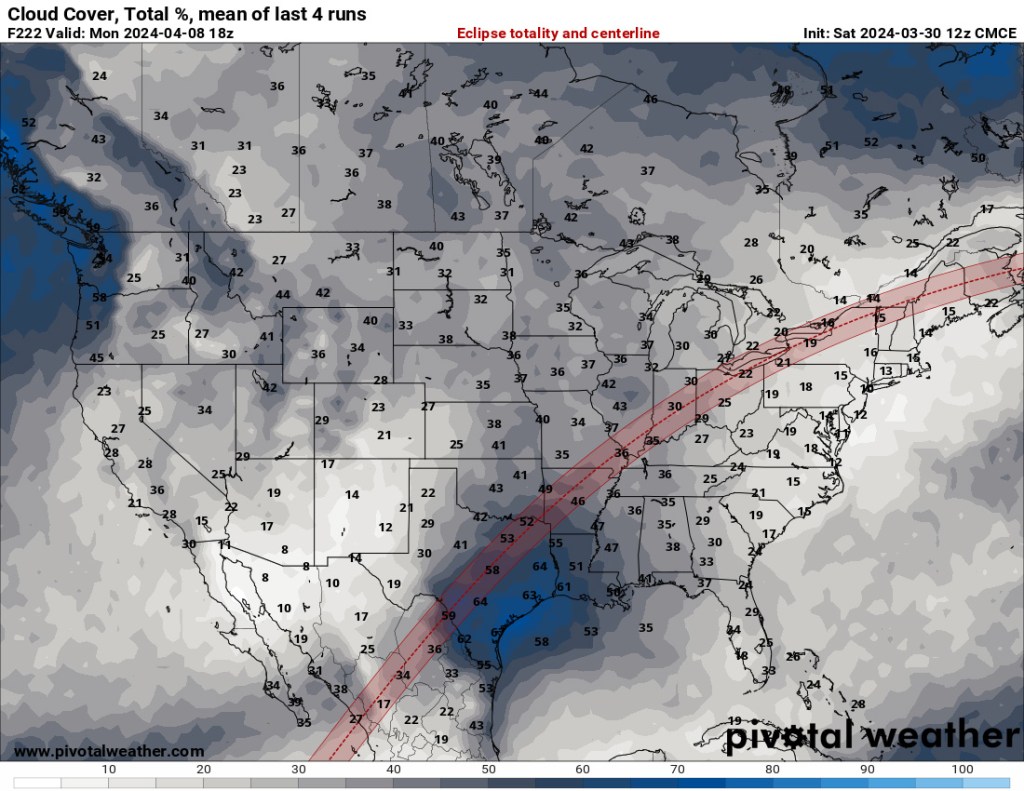

My destination was San Antonio, Texas. That’s where I had made a hotel booking more than a year earlier. The weather prospects in Texas were forecast to be best (at least according to the long-term averages) of any locations along the path in the U.S. or Canada. (I did not want to drive into Mexico.)

On March 30, with some trepidation, I set out down I-15 heading south. I got as far as Great Falls, Montana, my stop for night one. But it was to be a move in the wrong direction.

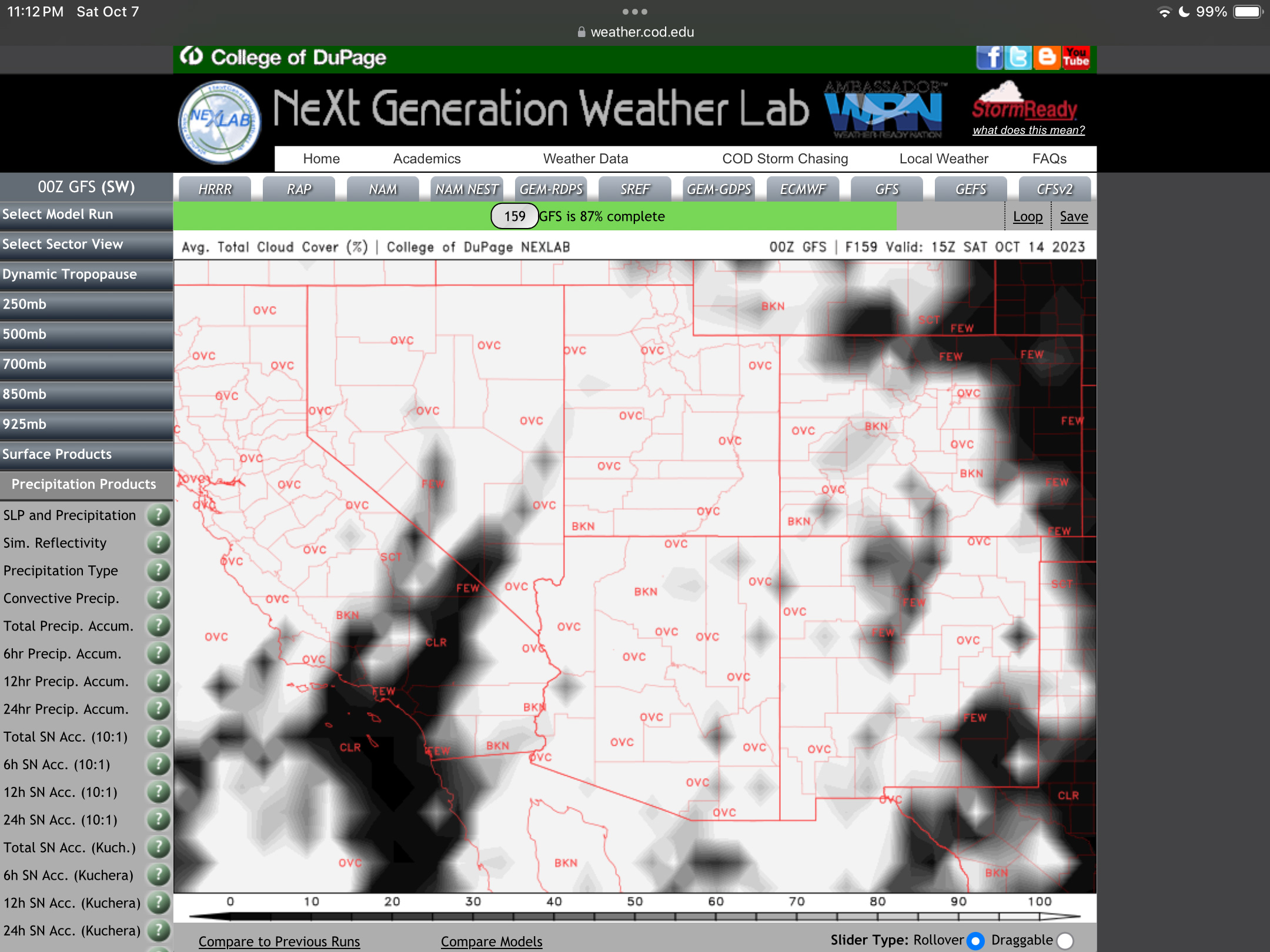

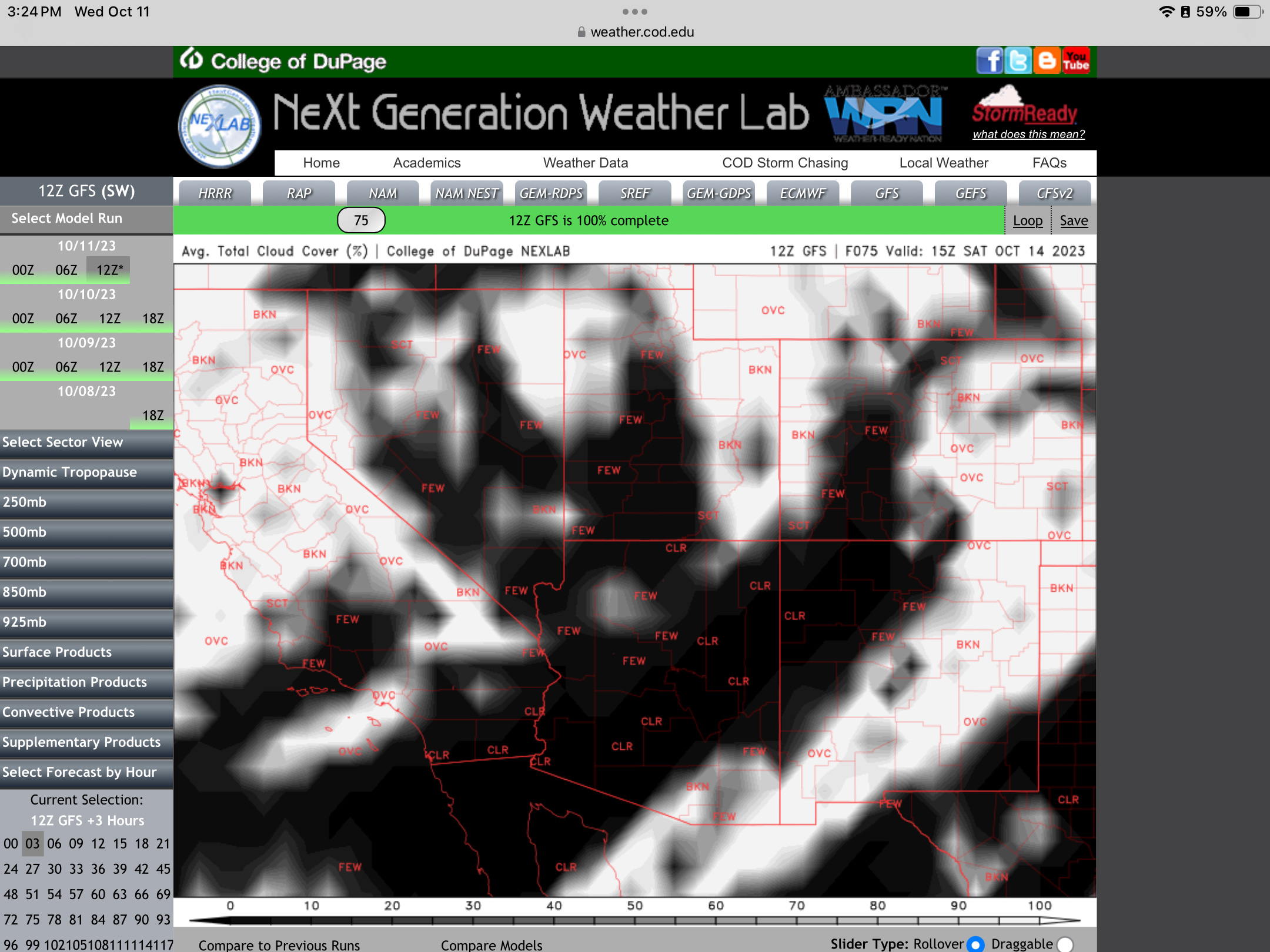

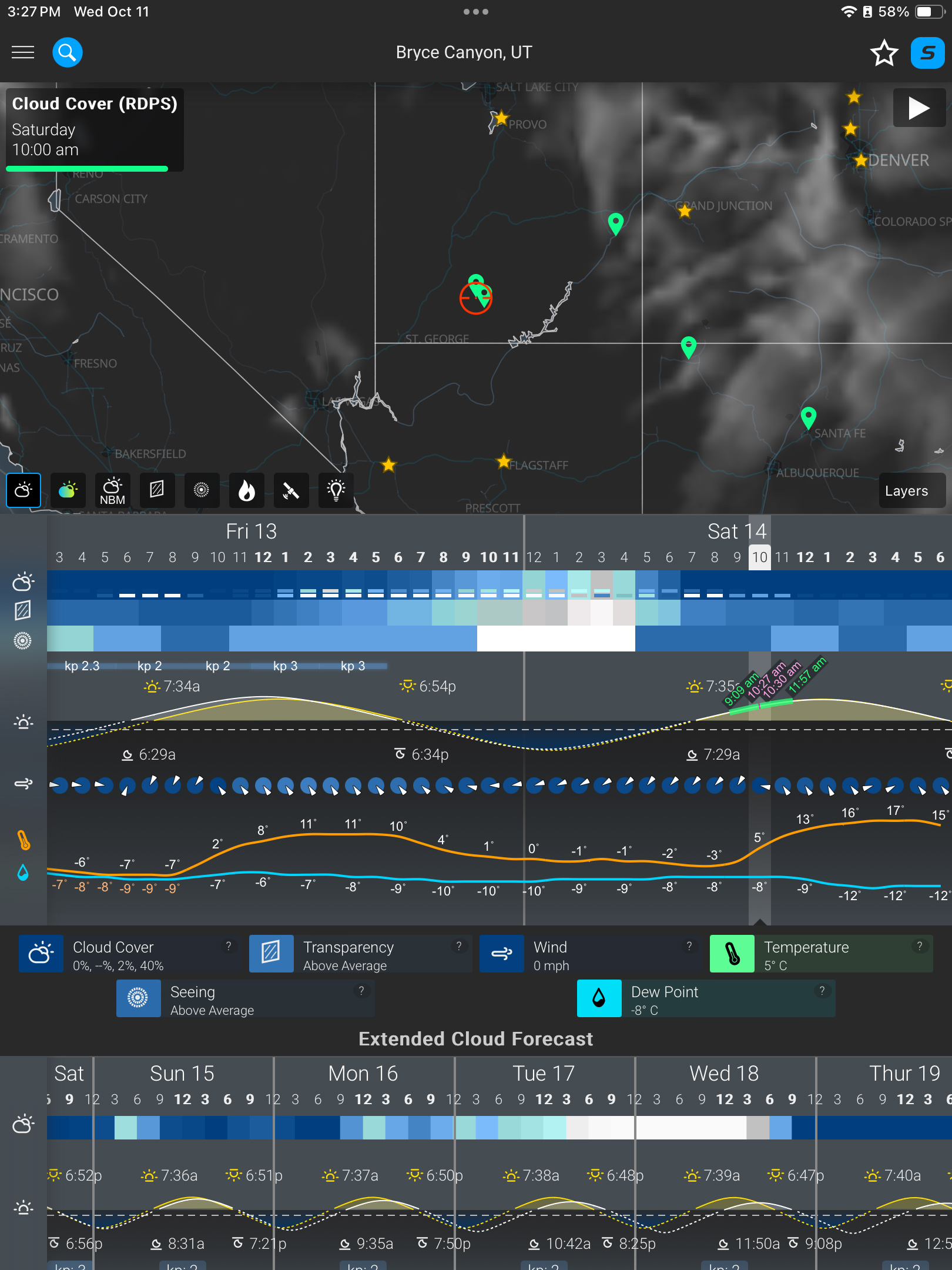

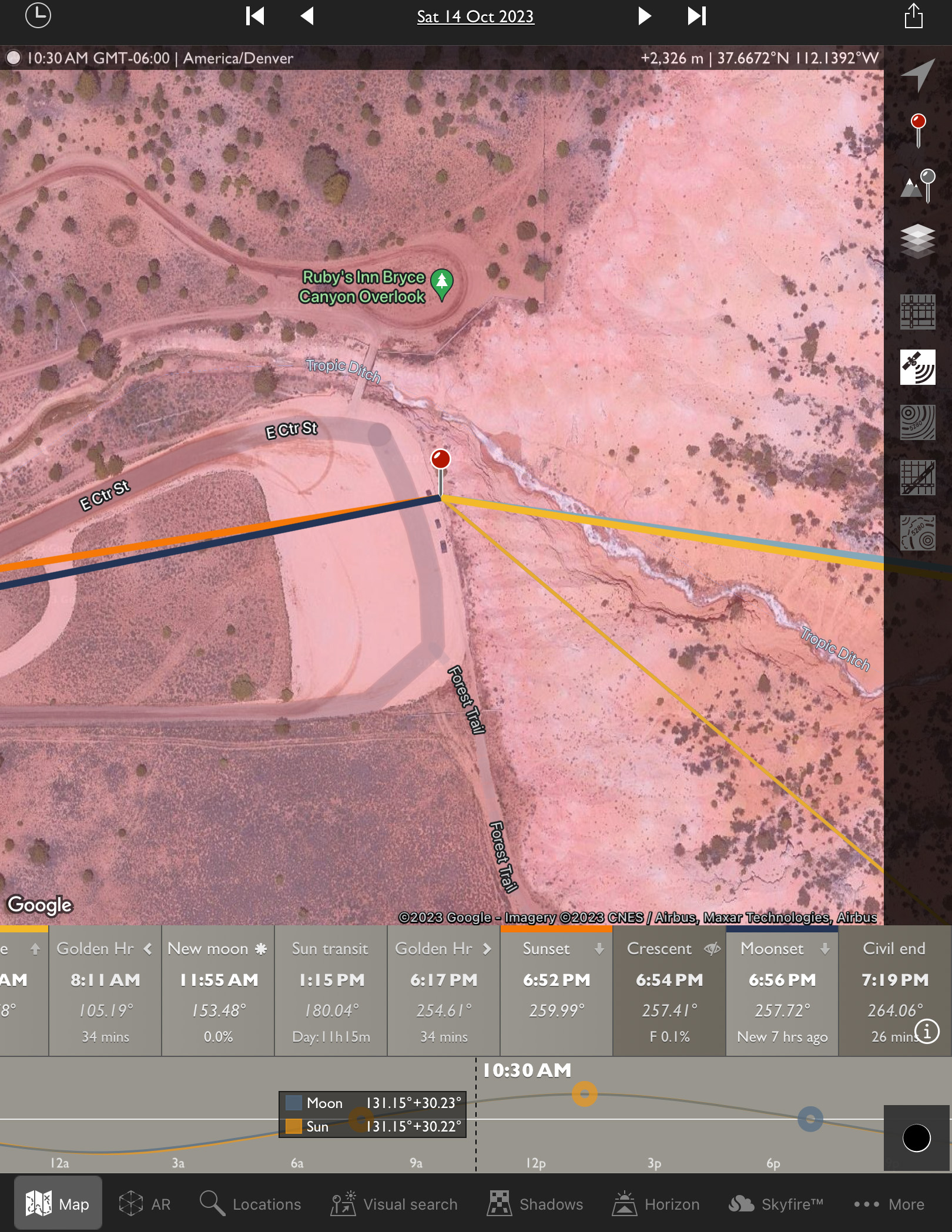

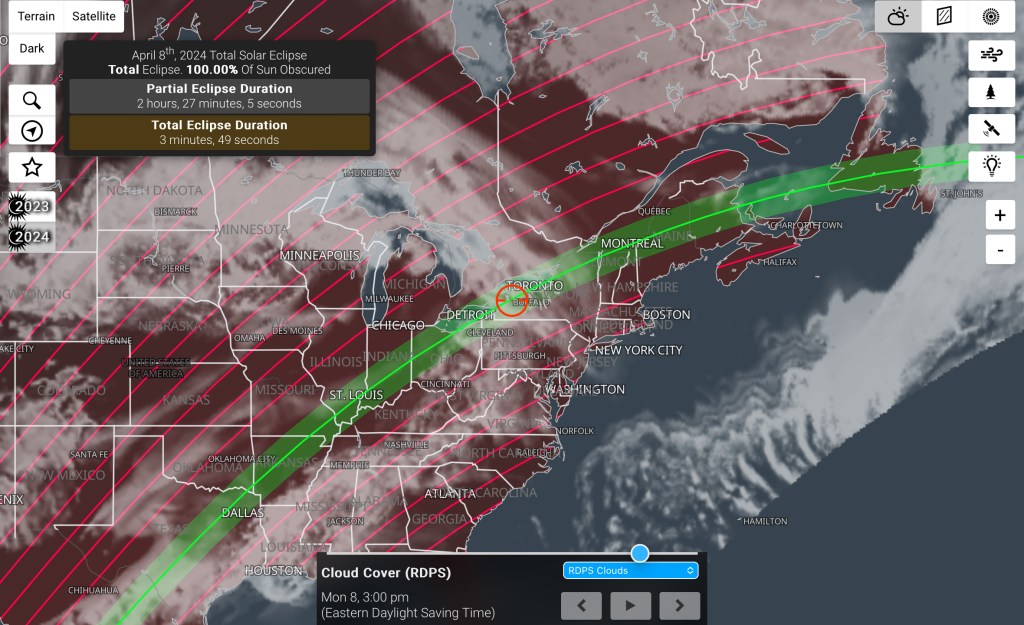

The various long-range weather models were all agreeing, even 10 days in advance, that Texas (covered in blue above) was looking poor for eclipse day. But eastern Canada looked good! That was the exact opposite of what had been expected.

So on Easter Sunday, I turned around and headed north, crossing back into Canada at a lonely border post in southwest Saskatchewan.

I proceeded east along the TransCanada, Highway 1. I decided against a route across the northern U.S. and around the southern end of Lake Michigan, to avoid severe weather forecast for the middle of the U.S.

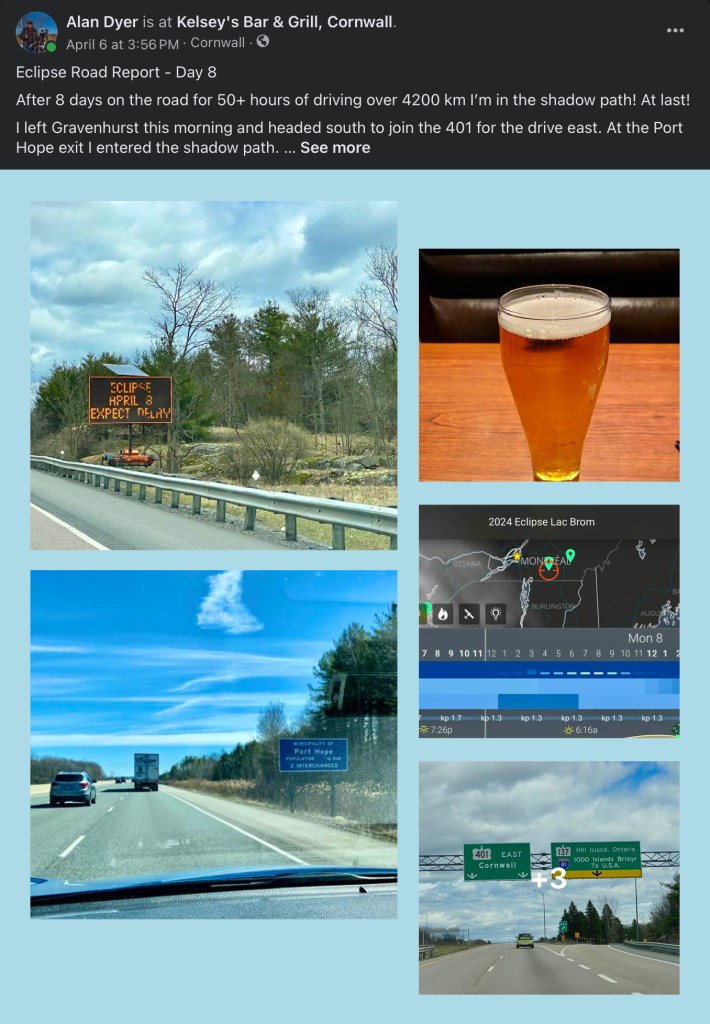

Along the way I posted my beer-du-jour travel reports, as above from Day 8, that day from within the shadow path at last!

I also stopped at the only total eclipse site, of the 16 I had seen previously, I have ever been able to re-visit. On February 26, 1979 I and a small band of friends from Edmonton viewed the mid-winter eclipse (the last one visible from southern Canada) from a median road (Firdale Road as it is now called) on the TransCanada Highway near Carberry, Manitoba. I found the spot again, where I saw (and shot with my Questar telescope) my first total eclipse of the Sun.

However, a day after entering Ontario, the bad weather caught up with me, forcing an extra night north of Lake Superior while the only highway across the region, Highway 17, was cleared of snow and re-opened at Wawa, the usual cross-Canada choke point.

My new destination (after abandoning the site in the Texas Hill Country) was to be southern Ontario.

However, as eclipse day approached and the weather predictions became more precise, it was apparent that Ontario would also be under some cloud. Southern Québec was looking better. So the Eastern Townships became my new Plan A site! I was running out of time!

I arrived on site in Québec with only a day to spare to check out the location I had found by exploring Google maps.

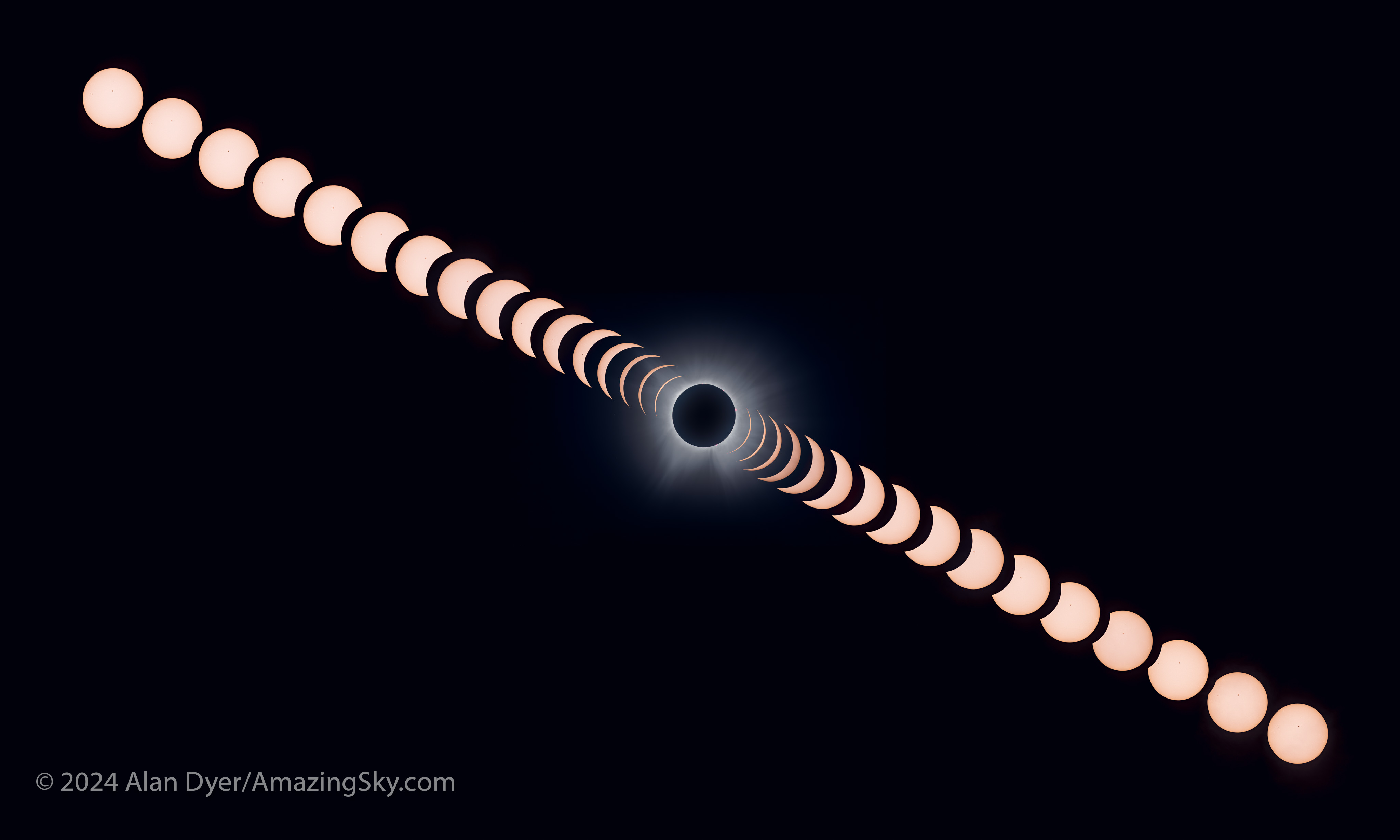

With the Sun lower in the mid-afternoon sky in Québec compared to the high-noon Sun in Texas, I decided to shoot a wide-angle scene of the eclipse over a lake, preferably with open water, not ice! That required a site with public parking on an eastern lakeshore.

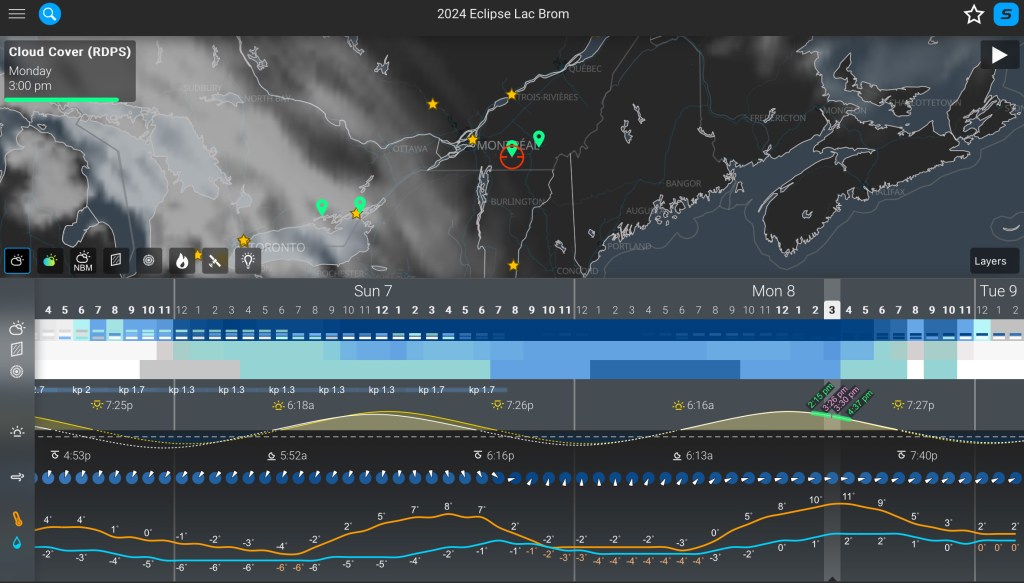

The site I found, then checked out on April 7, was on Lac Brome. It proved ideal — except for the thin cloud that was now predicted to drift through during the eclipse.

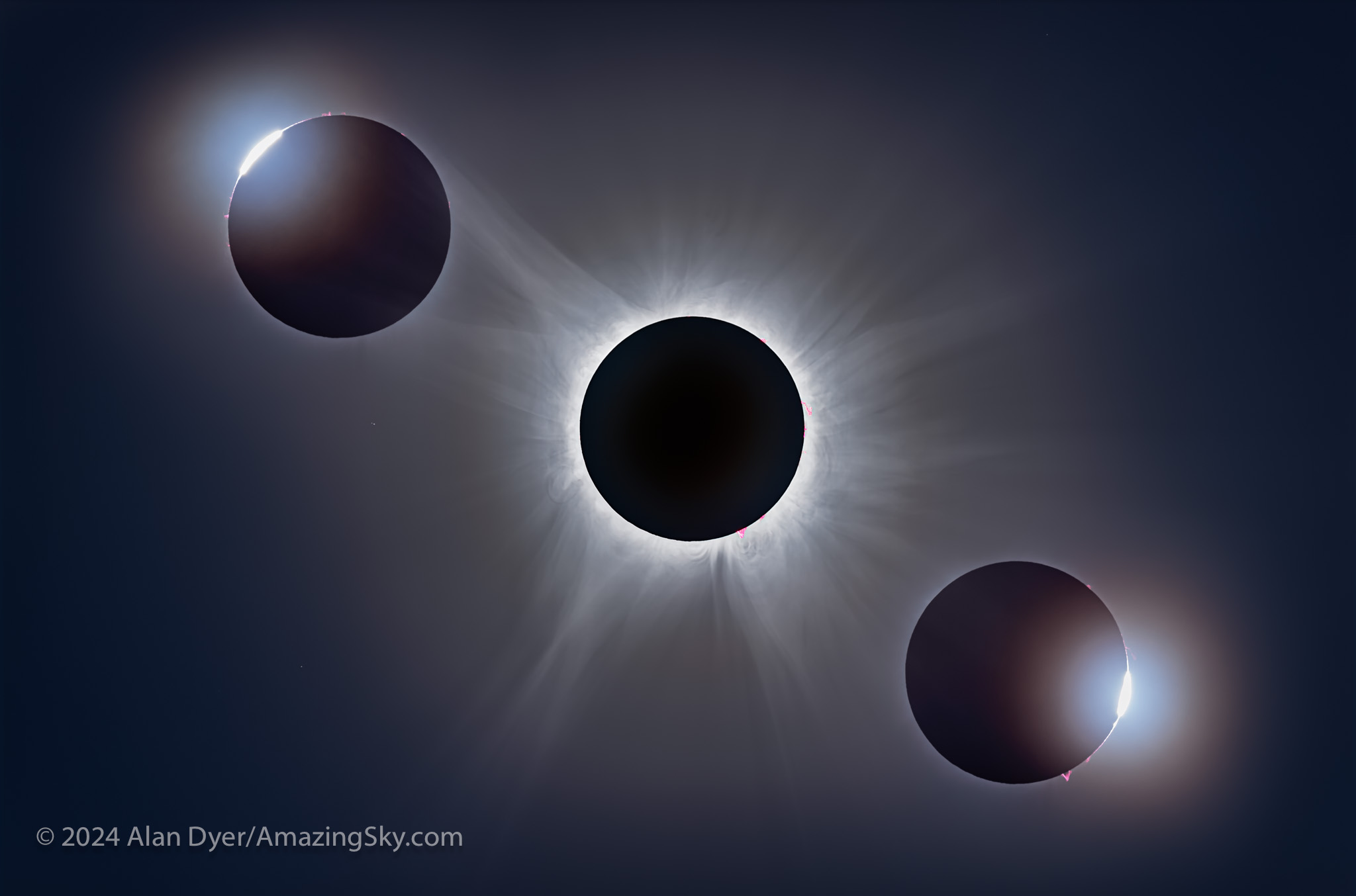

Sure enough, that’s just what happened. The cloud detracted from the eclipse only in preventing long-exposure images recording the outermost streamers in the Sun’s atmosphere.

I could have sought out clearer skies by going even farther east, but I was in a crunch for time and hotel rooms! As it was I was able to get rooms everywhere I wanted and at normal “non-eclipse” rates!

The Lac Brome site filled with cars during the day, with people from Québec and Ontario, but also from Alberta, and from Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Maine – at least those were the homes of the folks I enjoyed meeting on eclipse day.

Everyone had a great time and had a superb eclipse experience.

The lunar shadow arrived from the southwest, from the direction of the Sun, appearing as a dark cloud racing toward us. At the end of the eclipse the sky brightened first in that same direction, as the trailing edge of the shadow shot up across the sky. The clouds helped make the shadow edge more visible.

I shot with five cameras, just as I had done in 2017, possible only because I drove.

The main rig was my faithful Astro-Physics Traveler, a 105mm refractor telescope the company owner designed for his personal use at the 1991 eclipse in Mexico.

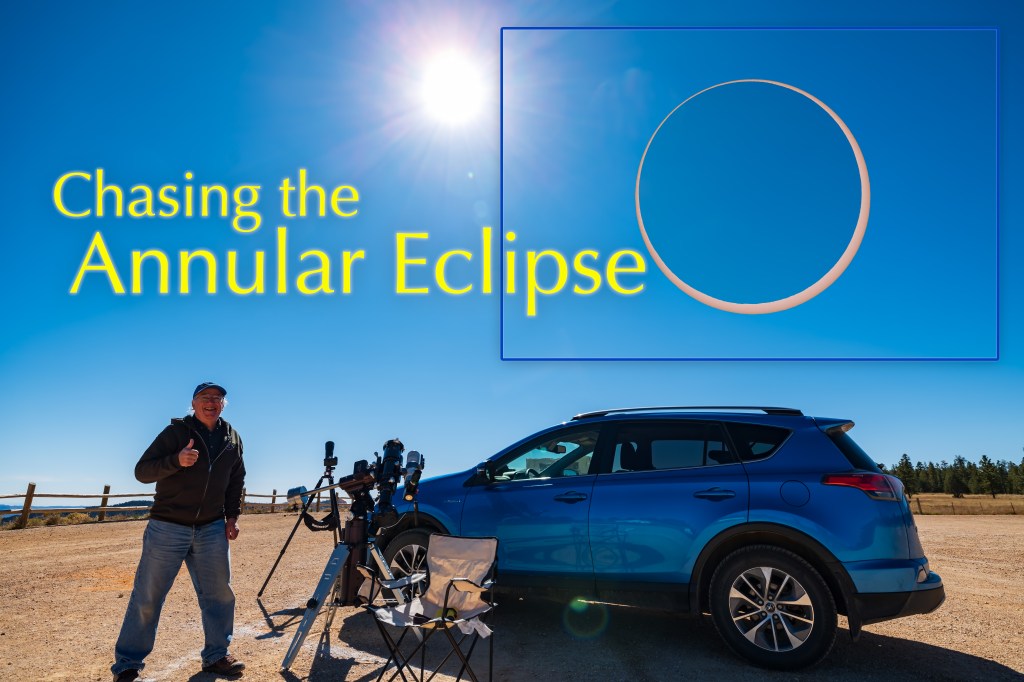

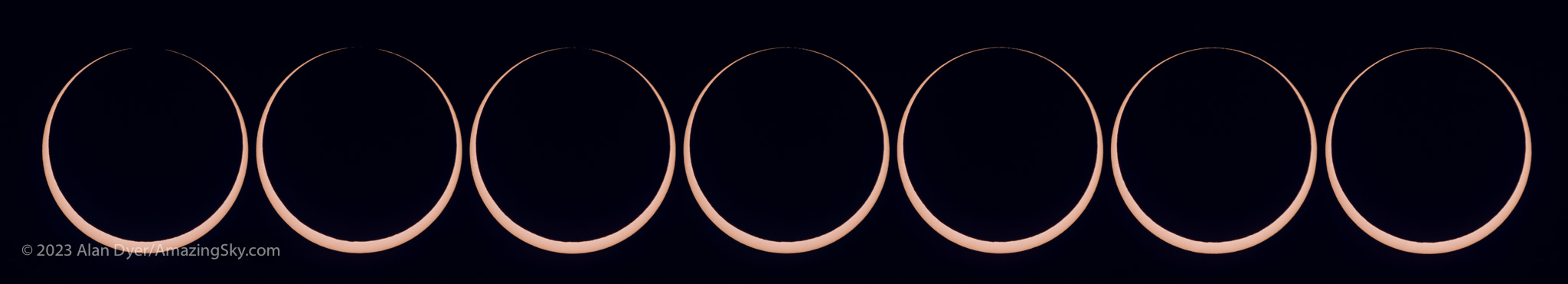

My Traveler, bought in 1992, has lived up to its name, having now been to six central solar eclipses: the annular eclipses of 1994 (Arizona) and 2023 (Utah), and the total eclipses of 1998 (Curaçao), 2012 (Queensland, Australia), 2017 (Idaho), and now 2024 in Québec, Canada. I paired it with the wonderful matching AP400 mount, which I had only just brought back with me the month before from Australia, where it had spent the last two decades.

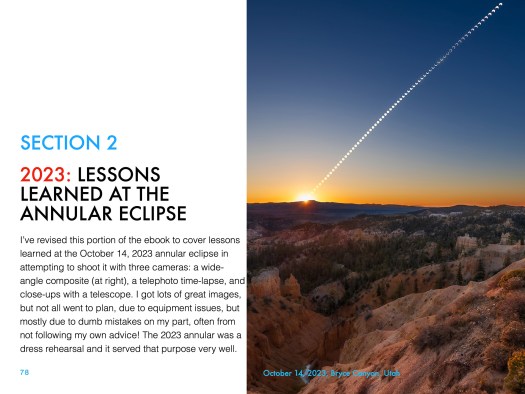

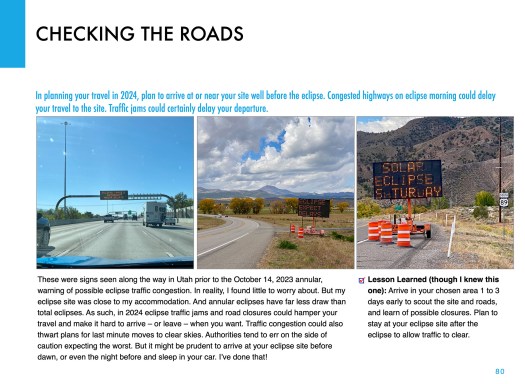

All the gear worked great. Unlike six months earlier for the October 14, 2023 annular eclipse in Utah, this time I remembered all the cables needed to have the telescope mount track the Sun.

I did mess up on a couple of settings (such as not framing the 4K movie camera as I should have – in pre-eclipse excitement I just forgot to check my chart). But none of the errors were serious.

Once started all my cameras, except for the one on the Traveler, ran unattended.

At this eclipse I was determined to get a good look at it through the small visual scope I had piggybacked onto the Traveler photo scope. While I had used a similar rig in 2017, I only thought to look through the visual scope 20 seconds before totality ended.

Not this year.

I got a great look at the eclipsed Sun, its corona structures, flaming pink prominences, and breakout of the red chromosphere layer just as totality ended. (You can’t easily see the chromosphere at the start of totality as it can be risky looking too soon through optics when the Sun’s blindingly bright photosphere is still in view.)

And yet, as at all eclipses, I found the naked eye view the most compelling. The “black hole” Sun looked huge and unearthly. While I had binoculars handy, the same 12×36 image-stabilized binoculars I bring to most eclipses, I completely forgot to look though them, just as I forget at most eclipses!

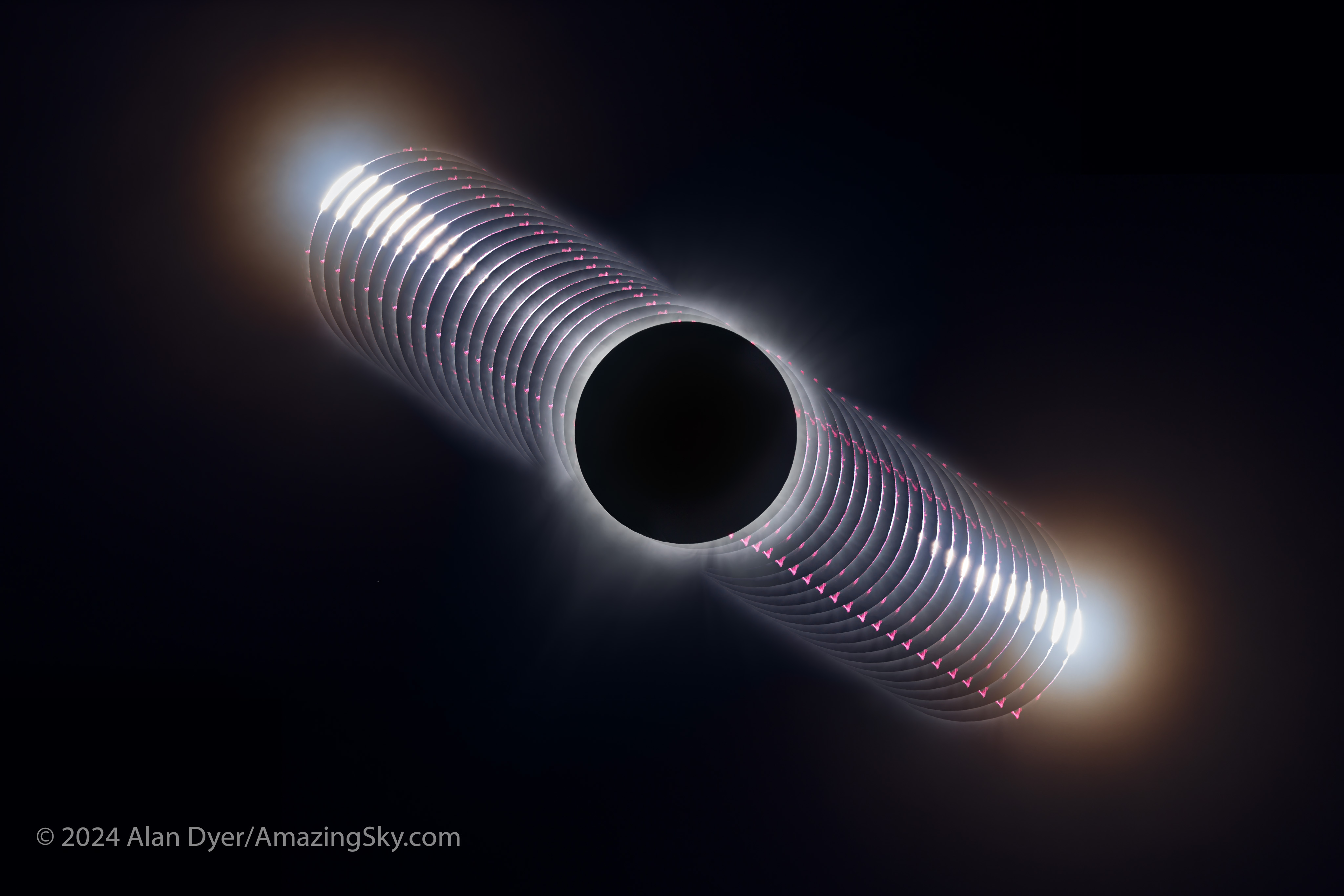

I shot all the images with the Astro-Physics Traveler 105mm refractor at 630mm focal length and f/6, with the Canon R5 at ISO 100. The partial phases are 1/800 or 1/400 second exposures through a Kendrick/Baader solar filter.

Wanting to record the full sequence, I shot the partial phases until the bitter end. But post-eclipse, people came over and had a look through my scope (I think mine was the only telescope on site). We had a great time exchanging impressions. The hand-held phone camera photos people showed me looked fabulous!

I looked for fleeting shadow bands just before and after totality (I laid out a white sheet on the ground for the purpose) but saw none, a negative observation confirmed by a fellow eclipse chaser at the site.

I did two live interviews for CBC Radio, for the Edmonton and Calgary stations, but not until after the eclipse ended. By the time I did those and finished packing away my carload of gear, it was 6:30 p.m., three hours after totality.

I was the last to leave the site, with fishermen now arriving for an evening’s catch.

I faced no traffic jams heading back to the hotel at Ste. Helen-de-Bagot. I processed and posted one eclipse image that night. And I revised the price (down to $2.99 U.S.) and description of my How to Photograph the Solar Eclipses ebook, as now only the big processing chapter is of any value, post-eclipse. It continues to sell.

On the long drive back to Alberta, with the pressure of having to make time now gone, I spent pleasant evenings stopping to see friends and family on the road home. So I didn’t start work on the complex blends and composite images I show here until I got home a week after the eclipse.

The 17-day-long drive was nearly 9,000 km over 100 hours behind the wheel. Was it worth it? Of course!

Would I do it again? It’s a moot question as none of the upcoming eclipses allows for a cross-continent drive. Except perhaps in July 2028 in Australia. But I suspect just heading inland a day or two over the Great Dividing Range will be enough to get away from winter coastal cloud in New South Wales. (Sydney is in the path, but so is a cottage I rented last month near Coonabarabran for my superb March stay under the southern skies!)

The next total eclipse of the Sun visible from anywhere in Canada will be August 22, 2044. I won’t have to drive anywhere, as it passes right over my house! But I will have to live that long to enjoy a eclipse from my own backyard.

I suspect this was my last chance to see – and drive to – a total eclipse in Canada.

— Alan, © 2024 amazingsky.com