After an absence of seven years it was great to be back under the fabulous sky of the Southern Hemisphere, home to the best deep-space splendours. Here’s my sky tour…

From 2000 to 2017, the year of my last previous trip Down Under, I had been travelling to the Southern Hemisphere, sometimes to Chile but most often to Australia, once a year or biennially. There’s just so much to see and photograph in the southern sky.

While the deep-south sky represents perhaps just 30 percent of the entire celestial sphere, it contains arguably the best of everything in the sky: the best nebulas, the best star clusters, the best galaxies, and certainly the best view of our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

No astronomical life is complete without a visit (or two or more!) to the lands south of the equator, ideally to a latitude of about 20° to 35° South. For the first time since 2017, I headed south this past March, in 2024. My belated blog takes you on a tour of the great southern sky.

NOTE: My blog is illustrated with lots of images, so it might take a while to load. Click or tap on an image to bring it up full screen. For the technically curious, I have included gear and exposure details in the captions.

Far Away in Australia

Yes, it’s long way to go — a 15-hour-flight from Canada. But Australia is my favourite destination down under. I can speak the language (sort of!), and have learned to drive on the left. Even after a seven year absence, my brain took only a few minutes to adjust once again to most of the car, and opposing traffic, being on the “wrong side” of me.

After a visit with the “relos” (Aussie for “relatives”) in Sydney and on the Central Coast of New South Wales, I loaded up all the telescope gear my folks had been kindly storing for me for two decades, and headed inland. Not really Outback. And not really “bush.”

My destination in March, as it usually has been on my many visits (this was my 12th time to Australia), was Coonabarabran in the Central West of NSW. It bills itself as the “Astronomy Capital of Australia.”

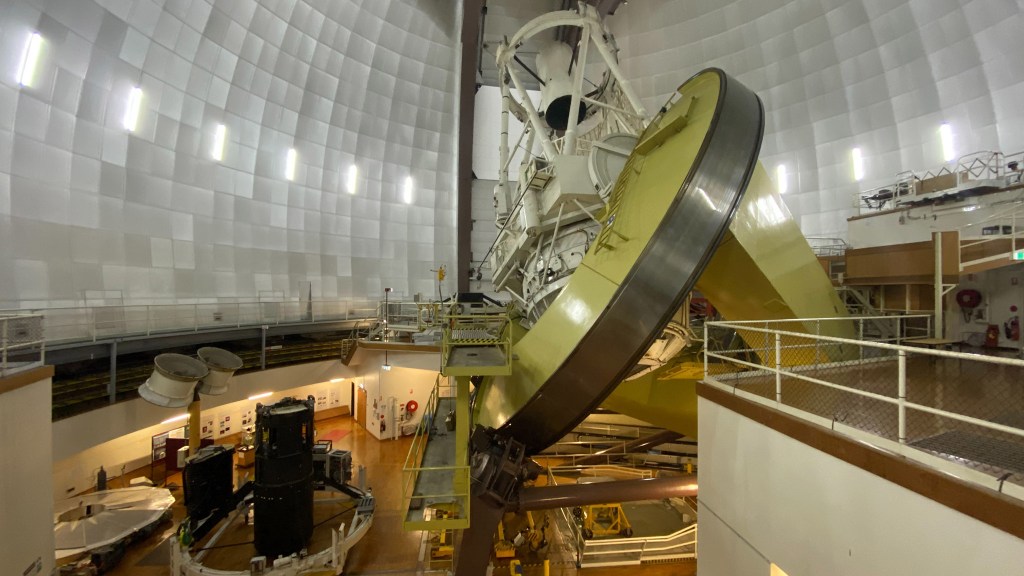

And rightly so, as nearby is the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia’s largest complex of optical telescopes (check the slide show above). I had a great tour again — thanks, Blake! — of the big 4-metre AAT that towers over the rest of the observatories on the mountain.

The Upside-Down Sky

My home for the first week in “Coona,” as the waning Moon got out of the way, was the Mirrabook Cottage off Timor Road, ideal as an astrophoto retreat. The view to the east and south (the view above) is partly obscured by gum trees, but not enough to prevent shooting targets around the South Celestial Pole, such as the Magellanic Clouds, as I show below.

The first order of the day upon arriving was to sort out my gear, to see if it was all working. My main Oz telescope, a legendary Astro-Physics Traveler refractor that I had stored in Australia since the early 2000s, came home with me in 2017, for use at the 2017, 2023, and 2024 solar eclipses in North America (the links take you to blogs for those eclipses) .

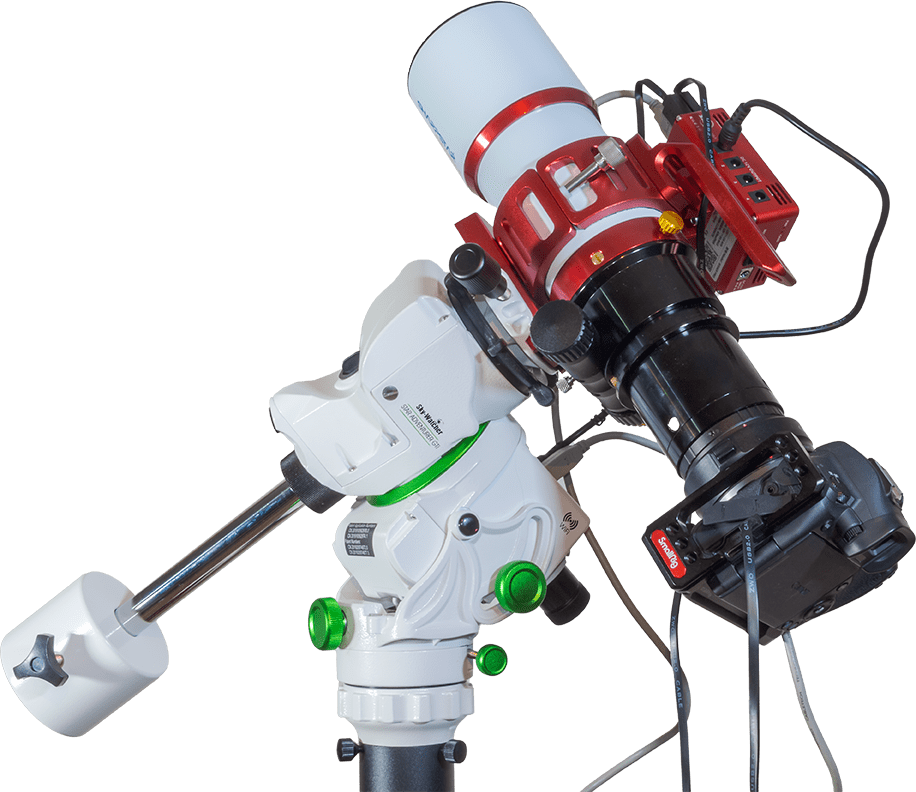

So this year I brought another little refractor with me, the diminutive Sharpstar 61mm EDPH III. Many of the images I present here I shot with the Sharpstar, on the veteran Astro-Physics AP400 mount I show above, which had lived in Australia for two decades. It came home with me this time, to use the very next month at the April total eclipse in Quebec. My blog with the final music video from that eclipse is here.

But I also brought a little star tracker, an MSM Nomad, which I reviewed here, just in case the old iOptron tracker I had in Australia, but hadn’t used since 2017, did not work. I needn’t have feared. It was the new Nomad that had issues, with the iOptron serving me well as a back-up for wide-angle Milky Way images.

From Mirrabook looking north affords a fine view of a sky familiar to us northerners — if we stand on our heads! Orion and the stars of “winter” are there but upside-down for us, with the constellations that are overhead for us at home, now low in the north.

I shot all the images presented here during my two-week Oz astrophoto extravaganza. I had clear skies every night, bar for a couple that were welcome breaks!

A more complete gallery of my images from Australia in 2024 is here on my Flickr site.

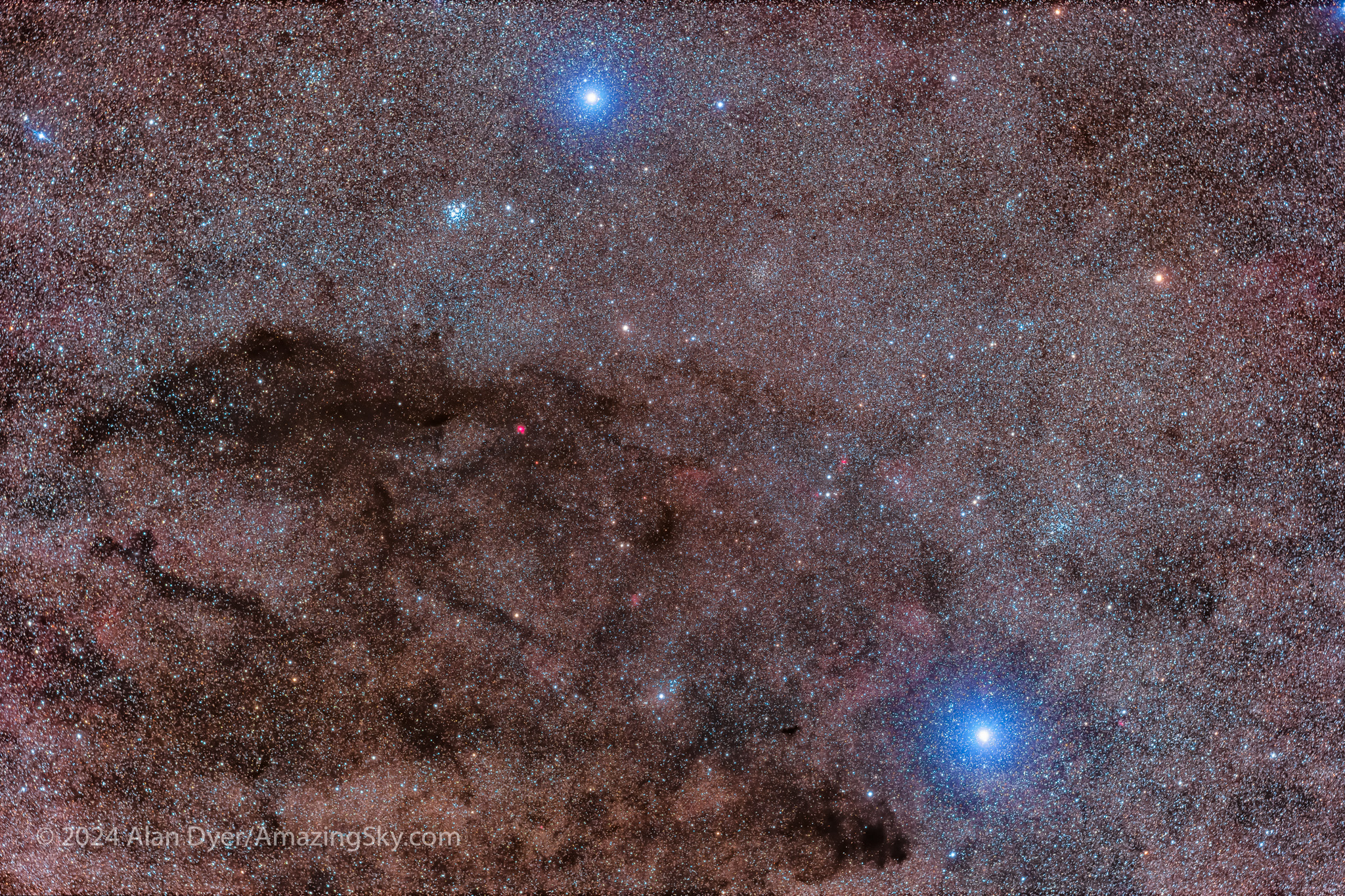

South of Orion, and overhead from Australia (as I show above), is the dimmer section of the Milky Way passing through constellations once part of the huge celestial ship Argo Navis, now broken into Puppis the Aft Deck, Vela the Sails, and Carina the Keel, the latter containing the second brightest star in the night sky, Canopus, second only to Sirius nearby in Canis Major.

Puppis and Vela

Though somewhat obscure and hard to pick out as distinctive patterns, Puppis and Vela are filled with deep-sky wonders.

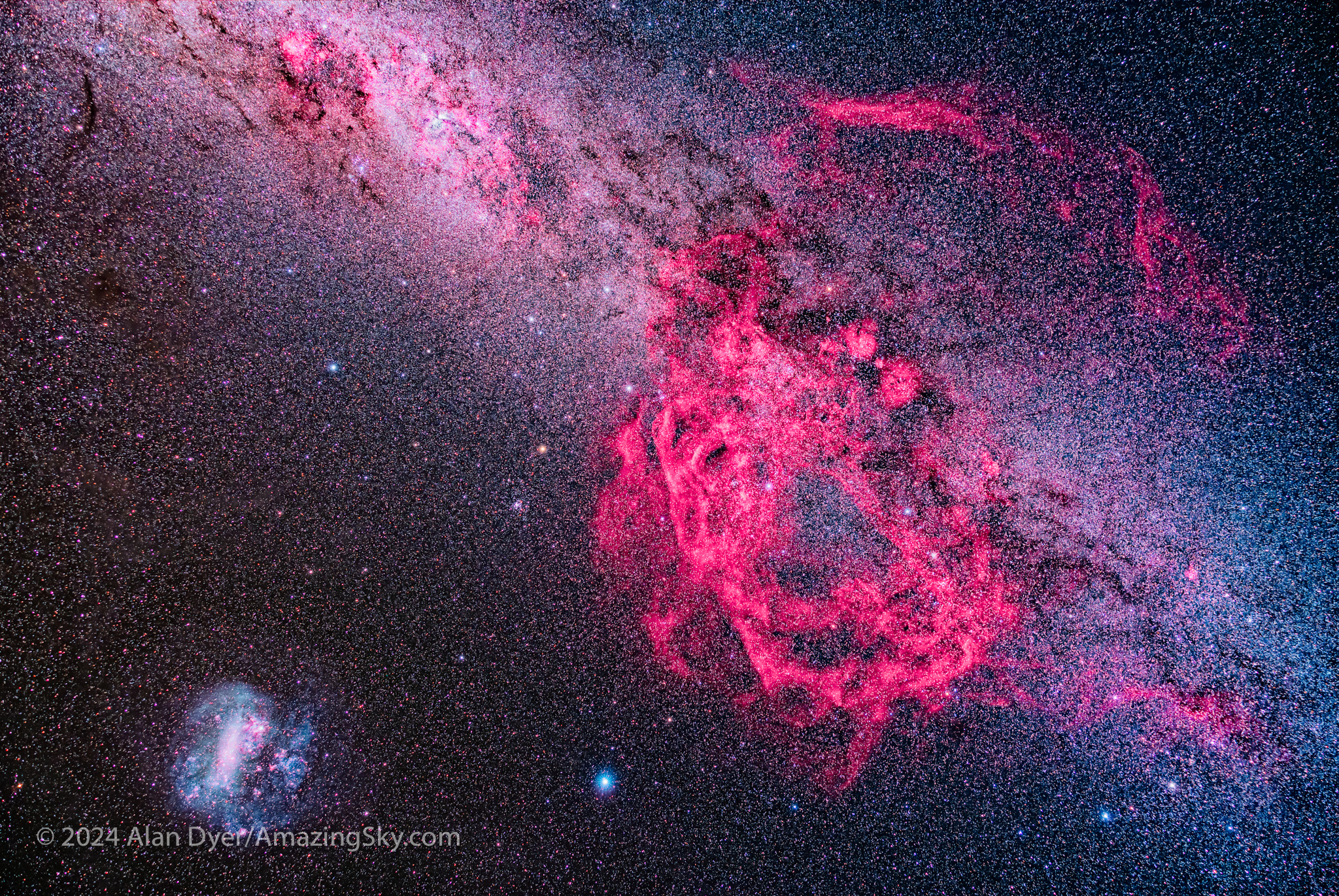

The biggest is so vast it covers as much sky as a hand length, held at arm’s length. But it is totally invisible to the eye, even aided by optics.

This is the huge Gum Nebula, discovered in 1955 by Australian astronomer Colin Gum, working at the Mt. Stromlo Observatory near Canberra. It might be a star-forming nebula shaped by stellar winds, or it might be the exploded debris of a nearby supernova star.

Within the Gum Nebula in Vela is a smaller complex of arcs and fragments I show below. This definitely is a supernova remnant, one that exploded about 11,000 years ago some 900 light years away. But it, too, is large, making it a perfect target for the little refractor, and a telephoto lens, with both versions below.

The area is also home to rich fields of bright star clusters (two are below), many intertwined with wreaths of star-forming nebulosity. These rival or exceed the more famous northern targets of the Messier Catalogue compiled between 1774 and 1781 by Charles Messier. It took several more decades before astronomers from the north catalogued the sky to the south.

Carina and Crux

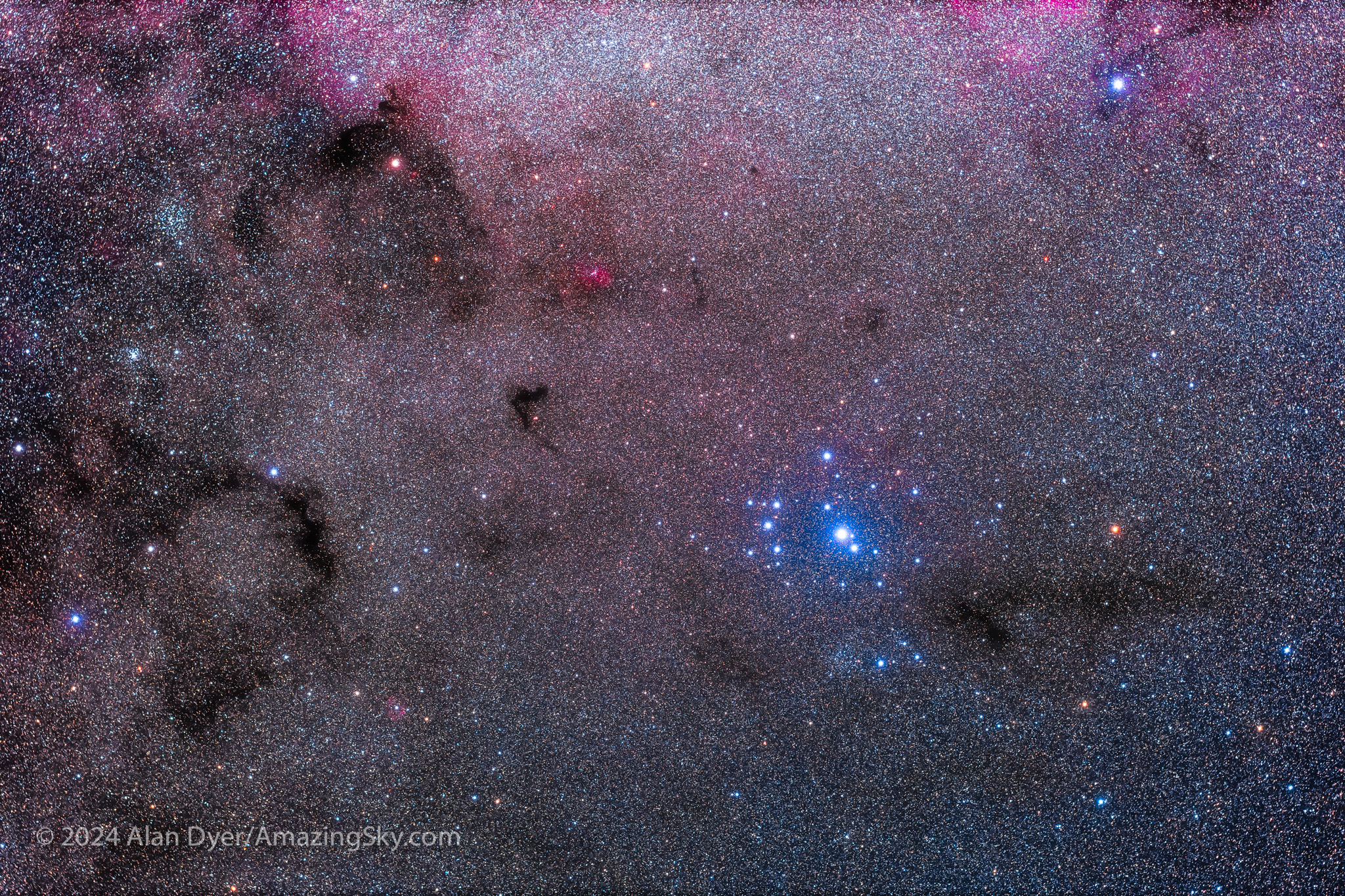

Continuing deeper down the Milky Way we come to its most southerly portion rich in nebulas and clusters that outclass anything up north. This is also the brightest part of the Milky Way after the Galactic Centre.

The Carina Nebula is larger than the more famous Orion Nebula farther north. In the eyepiece it is a glowing cloud painted in shades of grey and crossed by intersecting dark lanes of dust. Photographs reveal even more intricate details, and the magenta tints of glowing hydrogen.

At upper left is the “Football Cluster,” as Aussies call it, or the Black Arrow Cluster, aka NGC 3532. It is surely one of the finest open star clusters in the sky. John Herschel, who in the 19th century compiled the first thorough catalogue of southern objects, thought so. I agree!

Below the Carina Nebula is a brighter and bluer star cluster known as the Southern Pleiades, or IC 2602. Like many of the targets I show here, it is visible to the unaided eye and is a fine sight in binoculars, which are all you need to enjoy most of the southern splendours.

East of the constellation of Carina is the iconic and colourful Southern Cross, or Crux, a star pattern on the flags of Australia, New Zealand and several other austral nations.

Next to Crux is the darkest patch in the Milky Way, called the Coal Sack. Looking like a dark hole to the eye, in photos it breaks up into streaky dust lanes surrounded by famous star clusters, like the Jewel Box above it. Like many southern clusters, the aptly named (by Herschel) Jewel Box contains a variety of colourful stars.

Between Carina and Crux sits another wonderful field of clusters and nebulas, among them the more recently named Running Chicken Nebula. Can you see it? Above it is the Pearl Cluster, NGC 3766, also notable for its colourful member stars.

Below Crux is the little constellation of Musca the Fly (many southern constellations are named for rather mundane creatures and objects). One of Musca’s prime sights is the long finger of dusty darkness called the Dark Doodad — yes, that’s its official name!

The Magellanic Clouds

All the targets I’ve shown so far reside in our Milky Way. The next two objects, named for 16th century explorer Ferdinand Magellan, are extra-galactic.

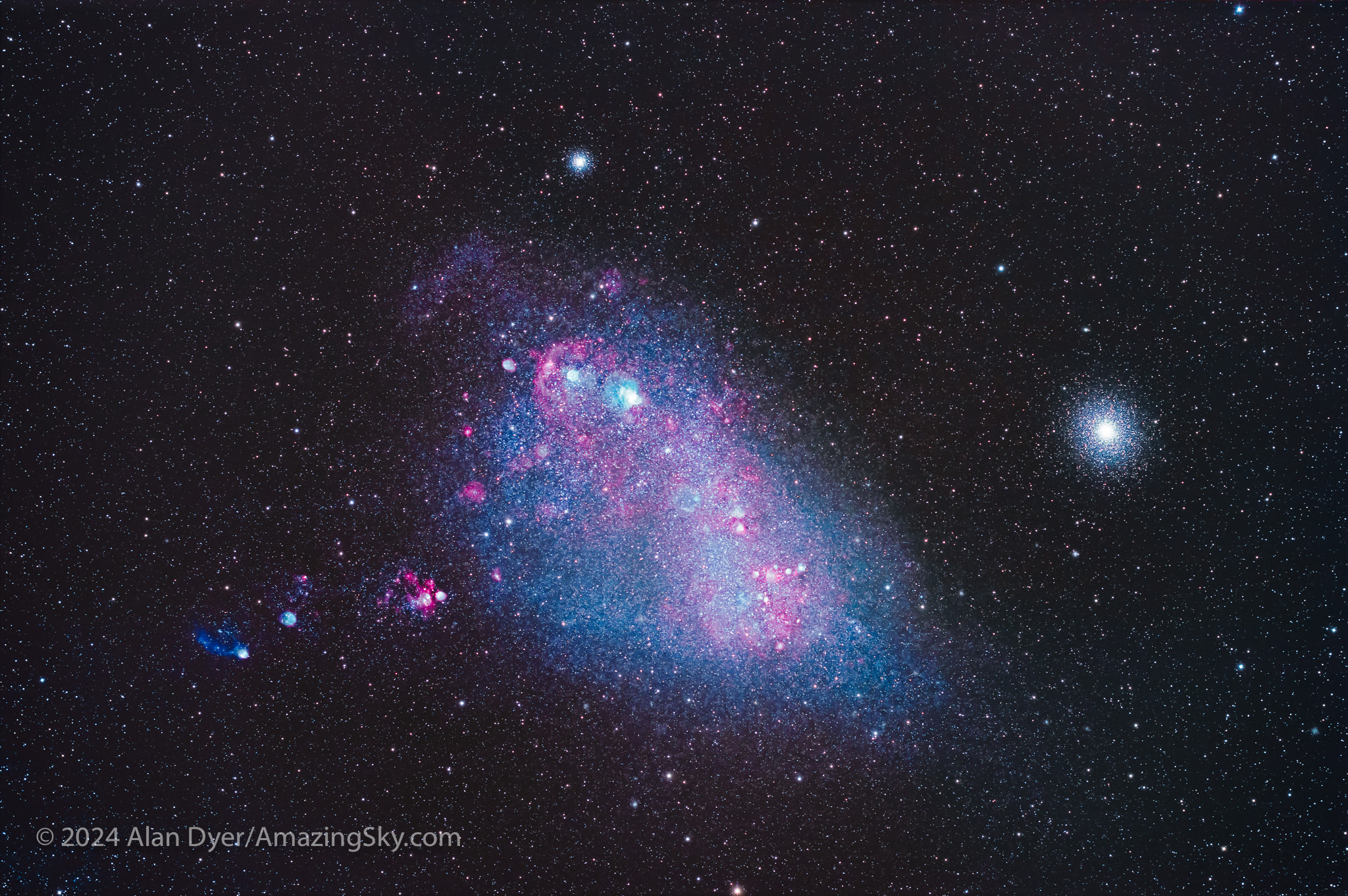

The Clouds are other galaxies beyond ours, but nearby. They are among the closest galaxies and are considered satellites of the Milky Way. Both are visible to the unaided eye, looking like detached bits of the Milky Way. For deep-sky aficionados, they are reason enough to visit the Southern Hemisphere!

The Small Magellanic Cloud contains many star-forming nebulas that glow in hydrogen red and oxygen cyan. It is most famous for its spectacular neighbour, the great globular star cluster called 47 Tucanae, here at right. It is not actually part of the SMC — 47 Tuc is more than ten times closer, on the outskirts of our Galaxy.

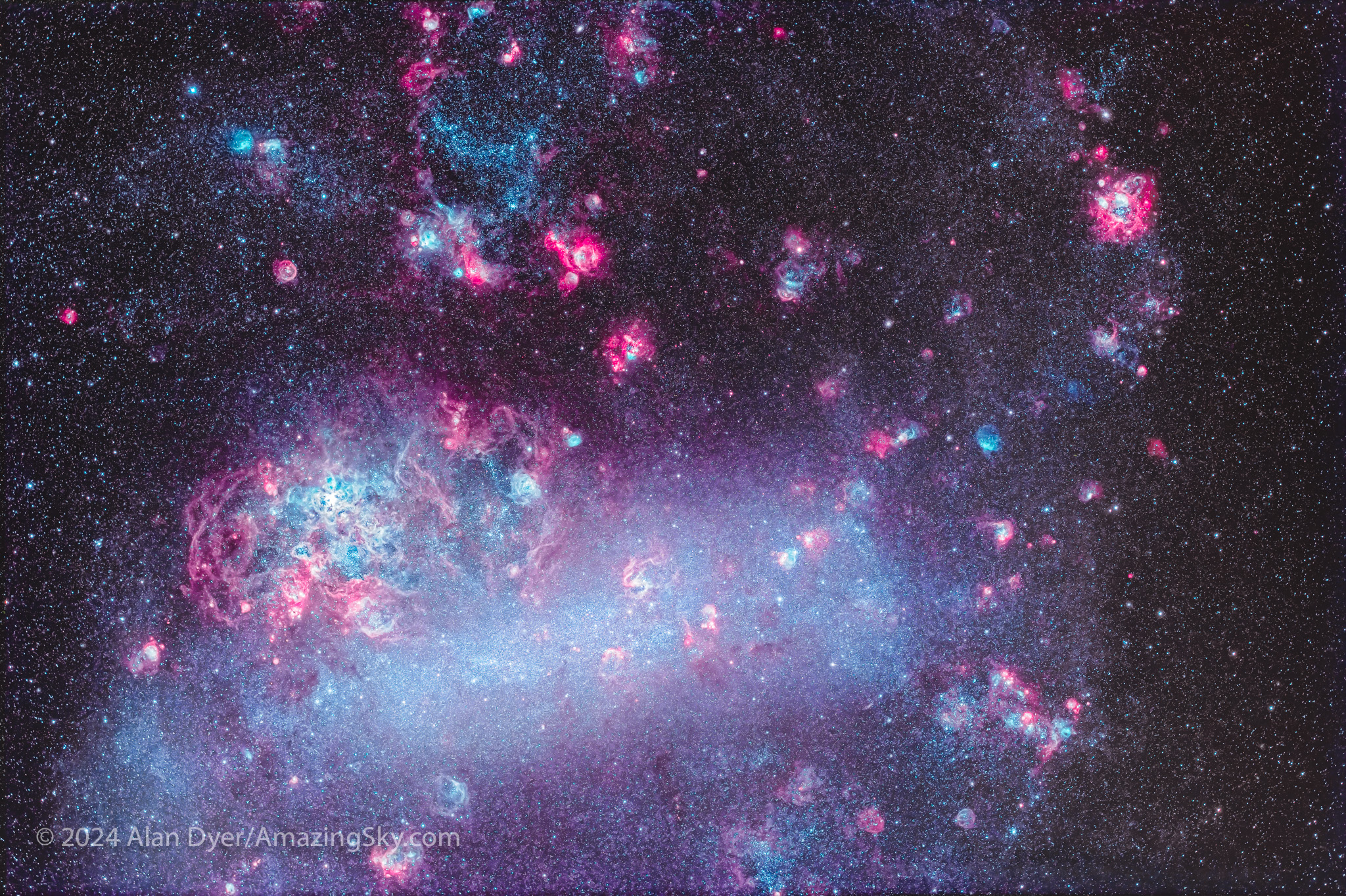

As rich as the Small Cloud is, it pales in comparison to its bigger neighbour, the LMC. The Large Magellanic Cloud is almost a universe unto itself. Astronomers have devoted their careers to studying it.

The biggest attraction in the LMC, one visible to the eye, is the Tarantula Nebula, the mass of cyan at left here. Many of the LMC’s nebulas emit light primarily from oxygen, not hydrogen. But figuring out which object is which can be tough. The LMC is filled with so many nebulas and clusters — and nebulous clusters — that no two catalogues of its contents ever quite agree on the identity and labels of all of them.

Northern Fields

The Magellanic Clouds are in the deep south, close to the Celestial Pole. A trip south of the equator is needed to see them. But on my trips to Australia I often like to shoot “northern” fields that I can’t get well at home in Canada.

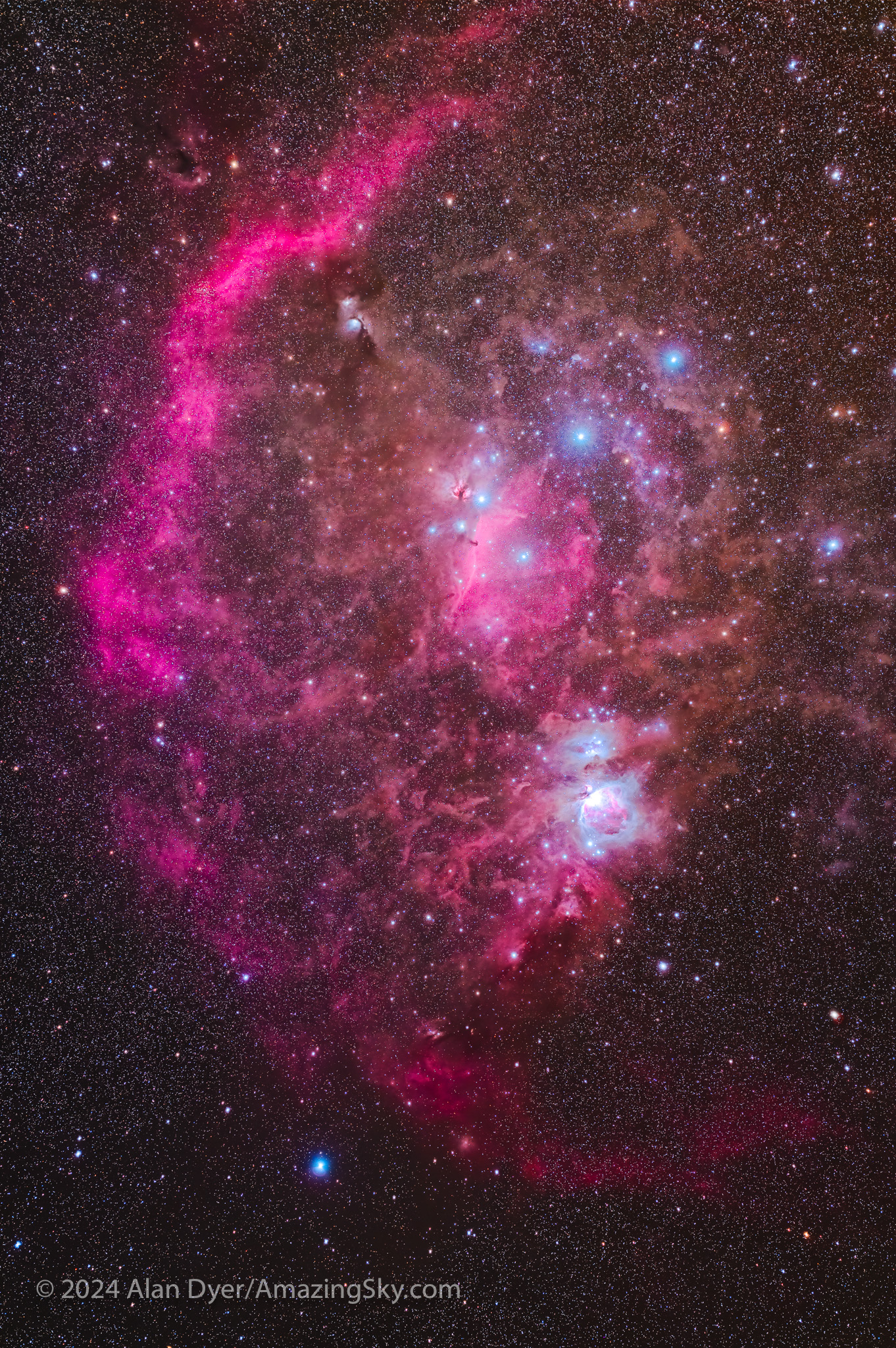

This is the Belt and Sword of Orion the Hunter surrounded by interstellar clouds. It’s low in my south from home, but high in the north down under. This is with a telephoto lens, not the telescope, captured under better and more comfortable skies than I have in winter in Canada.

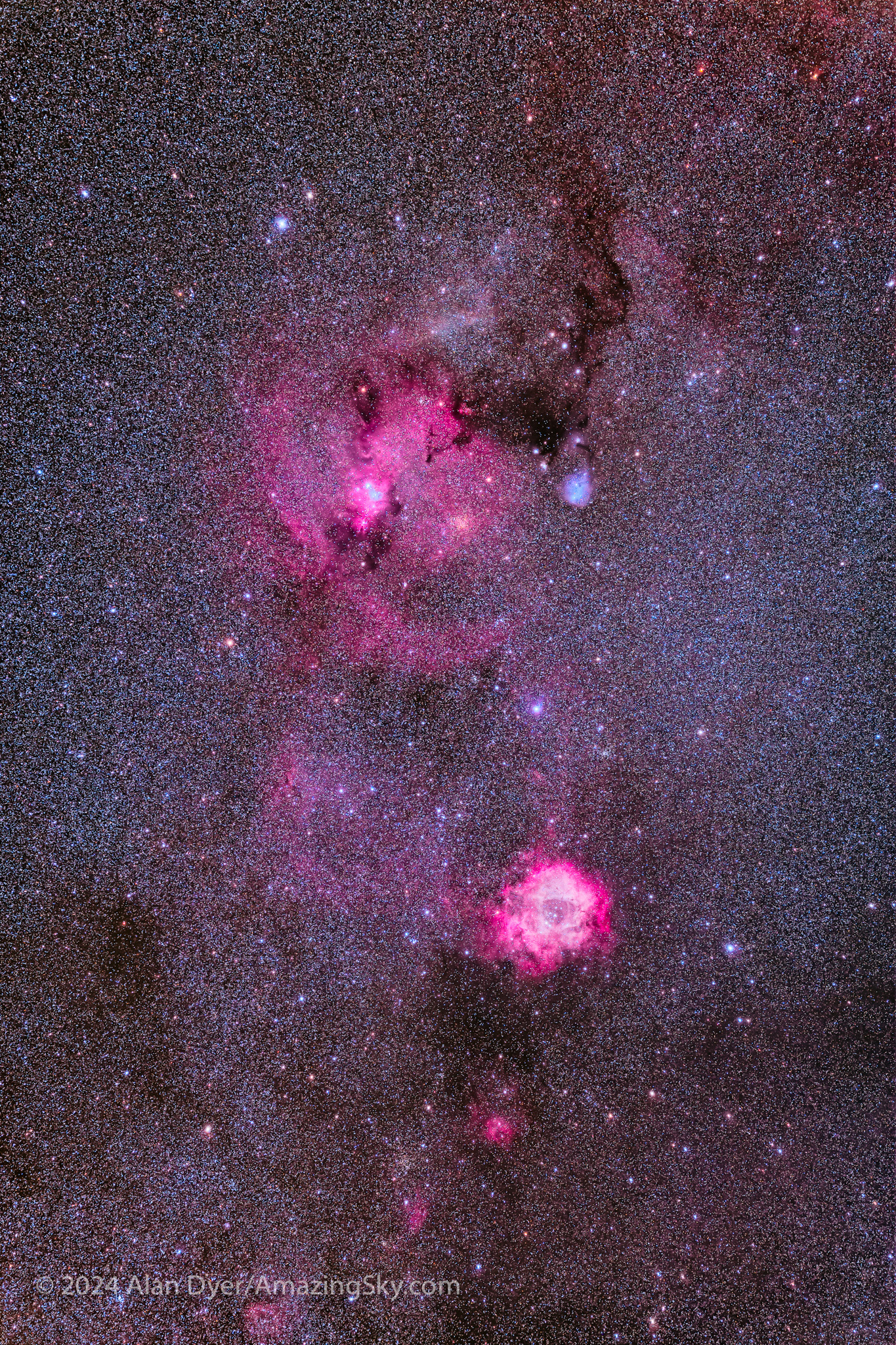

Nearby is another nebulous field but fainter, in Monoceros the Unicorn, containing the popular target, the Rosette Nebula, at bottom here. But there’s much more in the area that shows up only in long exposures under dark skies.

A target I’ve often had difficulty shooting for one technical reason or another is the Seagull Nebula straddling the border between Monoceros and Canis Major. I got it this time, together with a contrasting blue-green nebula called Thor’s Helmet, at lower left. It’s the expelled outer layers of a hot but aging giant star called a Wolf-Rayet star.

The OzSky Star Party

After a successful week at Mirrabook, I packed up and moved down the road to the Warrumbungles Mountain Motel, home to the annual OzSky Star Safari I have now attended six times over the years. (I see as of this writing it is almost sold out for 2025!)

Limited to about 30 people, OzSky (flip through the slide show above) caters to ardent amateur astronomers from overseas who want to revel in the southern sky, aided by the presence on site of a field of giant telescopes, delivered and set up by a great group of Australian astronomers, who show everyone how to run the computer-equipped scopes. And with tips on what to look at beyond the top “eye candy” targets I’m presenting here.

The views of the southern splendours through these 18- to 25-inch telescopes are well worth the price of admission!

It is always a great week of stargazing and camaraderie. If you are thinking of “doing the southern sky,” I can think of no better way than by attending OzSky. While it is primarily geared to visual observers, a growing number of attendees have been lured into the “dark side” of astrophotography.

March and April, austral autumn, are good months to go anywhere down under, as you get views of the best of what the southern sky has to offer. The Milky Way is up all night, just as it is six months later in our northern autumn. That’s when I made my complementary Arizona pilgrimage this year, blogged about here.

The Dark Emu Rising

One of the great naked-eye sights at OzSky in its usual months of March or April is the Dark Emu rising after midnight.

It is an Australian Aboriginal constellation made of lanes of obscuring interstellar dust, from the Coal Sack on down the Milky Way to past the Galactic Centre. It is obvious to the eye — a constellation made of darkness.

Sagittarius and Scorpius

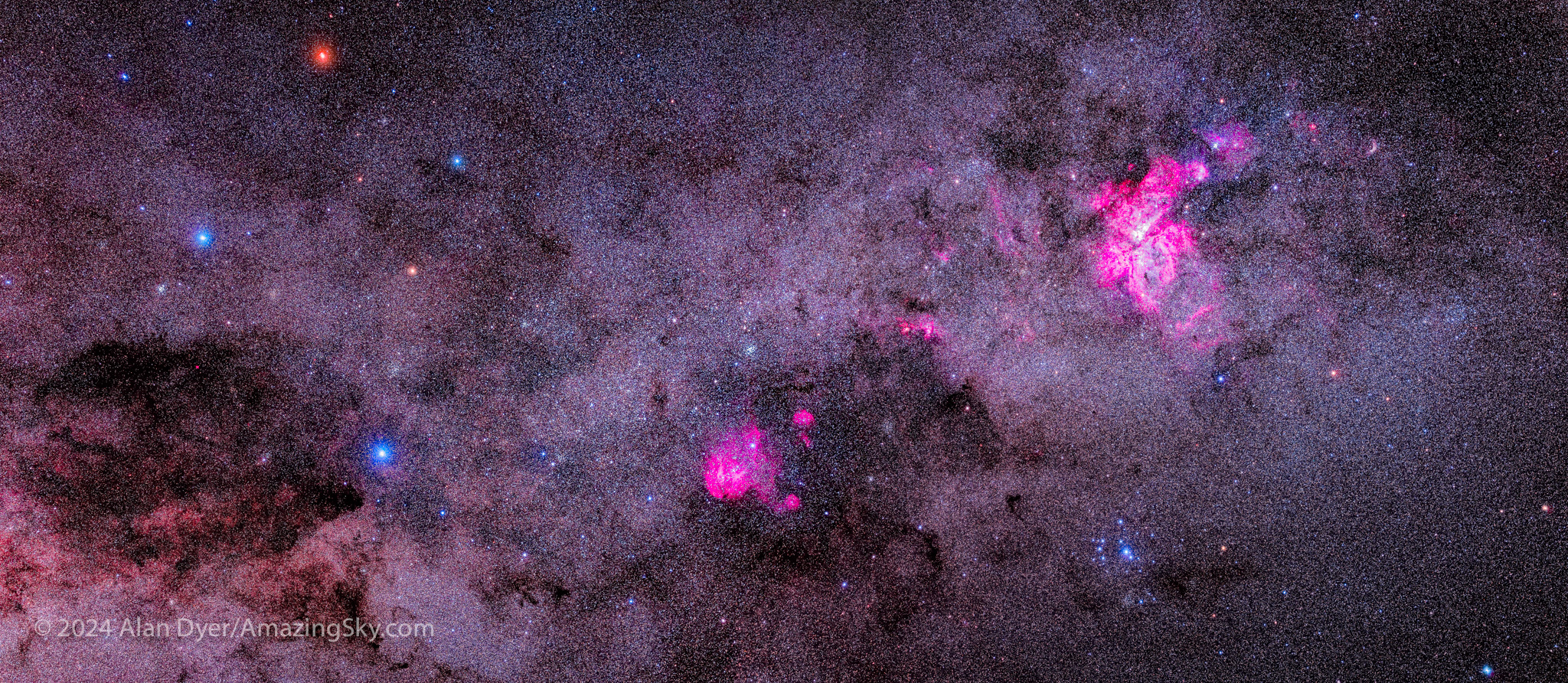

Late at night in the austral autumn months, the centre of the Galaxy region in Sagittarius and Scorpius comes up, presenting such a wealth of fields and targets it is hard to know where to begin.

Yes, we can see this area from up north, but there’s nothing like seeing Scorpius crawling up the sky head first, and then shining from high overhead by dawn.

Fields like this in the Tail of Scorpius are below my northern horizon at home. And it would still be low from a southern U.S. site, where natural green or red airglow can spoil images. I’ve never had an issue with airglow in Australia. Oz skies are as dark and clean as I have ever experienced.

The Southern Milky Way

The grand finale of a night at OzSky, or anywhere in the southern hemisphere in autumn, is the celestial sight that I think ranks as one of the sky’s best, up there with a total solar eclipse.

That sight is the jaw-dropping pre-dawn panorama of our Galaxy stretched across the sky, with the bright core overhead and its spiral arms out to either side. It is obvious as a giant edge-on galaxy, with us far off-centre. The image above frames the entire Dark Emu.

One of my projects this year, for a moonless night with little likelihood of clouds coming through, was to work photographically along the Milky Way, down from Orion into Puppis and Vela, through Carina and Crux, and into Centaurus, then finishing with the galactic core area of Scorpius and Sagittarius.

The resulting 180º panorama, made of 11 segments shot at 32° South, was an all-night affair, interrupted by a nearby tree and the oncoming dawn. It complements one I shot six months later from 32° North in Arizona. That panorama is included in my Comet Chasing blog.

The Moon Returns

OzSky, as are all star parties, is timed for the dark of the Moon. By the end of the week, with everyone well and truly satiated by starlight and dark skies, the crescent Moon was beginning to appear in the west. (Yes, that’s a young waxing evening Moon, here near Jupiter on March 14, 2024.)

It was time to pack the telescopes into their trailers, and for everyone to head back home, whether that be in Australia or elsewhere in the world.

If You Go…

If you travel to the Southern Hemisphere, at the very least take binoculars and star charts, especially simple “beginner” charts, as you’ll be starting over again identifying a new set of patterns and stars.

For astrophotography, a star tracker is all you need, plus of course a camera and lenses. Focal lengths from fish-eye to telephoto can all be put to use. But many of the best fields are suitable for framing with no more than a 135mm lens, as I used for some of the images here.

But take good charts to identify the location of the South Celestial Pole in Octans the Octant. With no bright “South Star,” it can be tricky getting that field into your polar alignment sighting scope. Once aligned, I tend to leave my rig set up where it is, and not have to repeat the process each night. That’s why it’s nice to base yourself under dark skies at a cottage like Mirrabook, and not be on the road and at a different site every night.

If you want to have a telescope with you, one of the current generation of small (50mm to 70mm) apo refractors is ideal, either to look through or shoot through. For imaging, a small equatorial mount is essential, but can be tough to pack with its tripod. And you need to power it. The little Sky-Watcher Star Adventurer GTi powered by its internal 8 AA batteries, but on a collapsible carbon fibre tripod, is a good choice.

For visual tours, the OzSky Star Safari will provide all the eyepiece time on big scopes you could ask for. It is imaging where you are on your own to come fully equipped and self-contained.

When will I be back? Perhaps not in 2025. But 2026 is a possibility, maybe a little later in austral autumn to get the Galactic Centre up sooner and higher before dawn. I’ve been to Australia in the winter months of June and July and it’s too cold! May perhaps.

If you go once, you will be bitten (we hope not literally by one of Oz’s killer critters!) by the southern sky passion.

The only downside is that when I get home, often to poor weather, but even when skies are clear, I find that the home skies tend to lose their excitement and attraction. They just can’t compare to the great southern skies.

— Alan, December 18, 2024 / AmazingSky.com