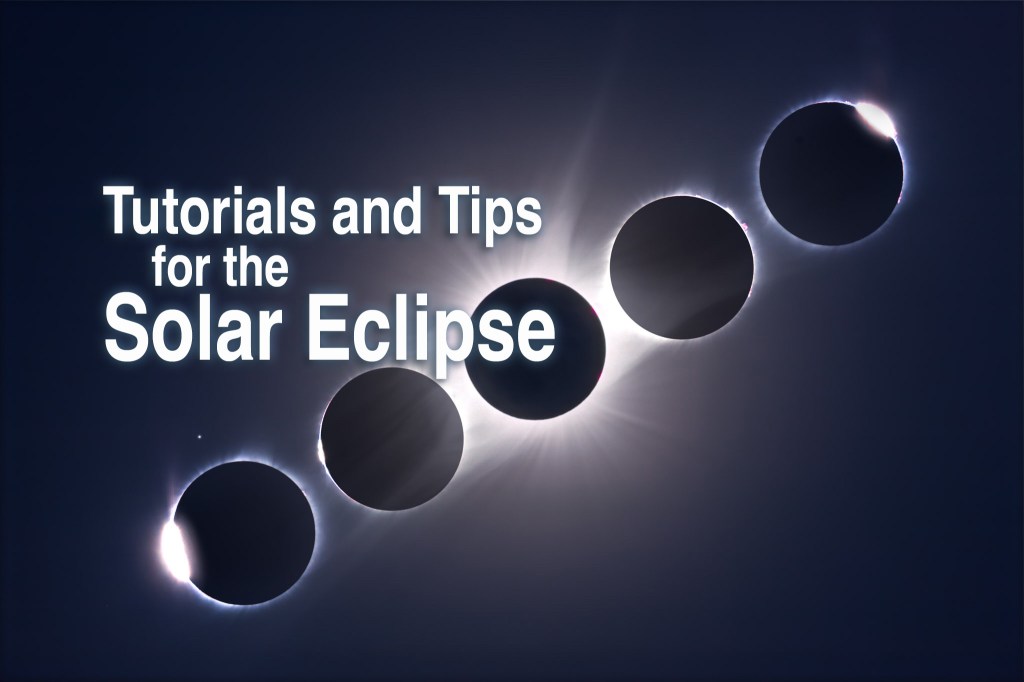

As eclipse day approaches here are some tips and video tutorials from me about how best to capture the total eclipse of April 8, 2024.

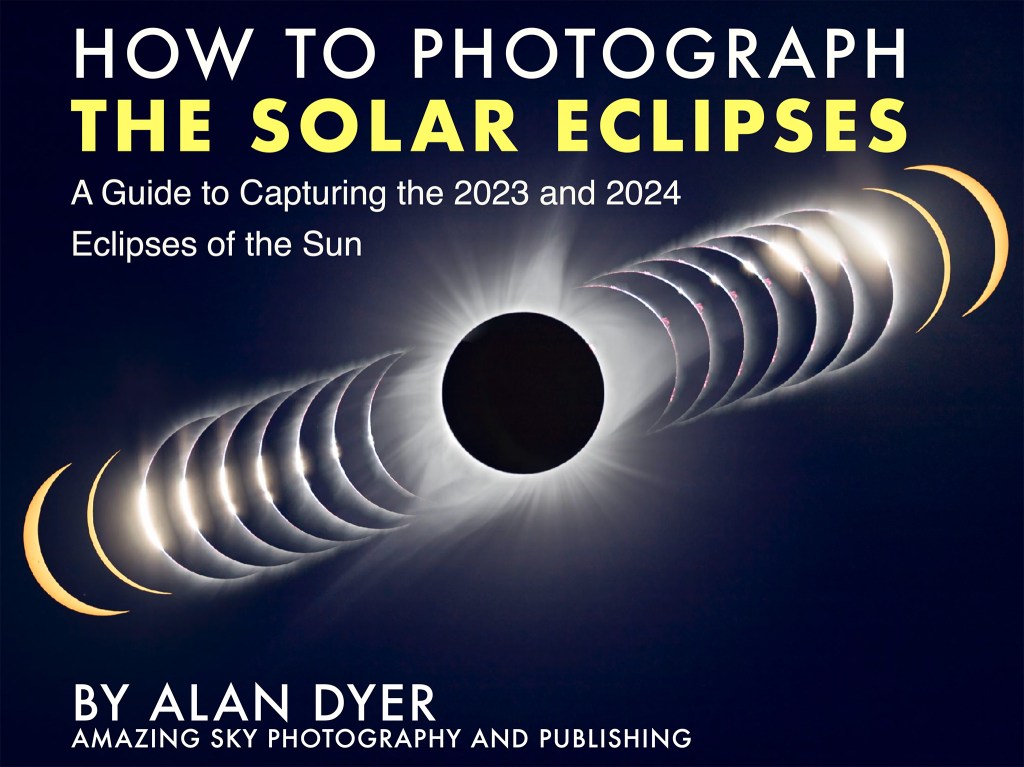

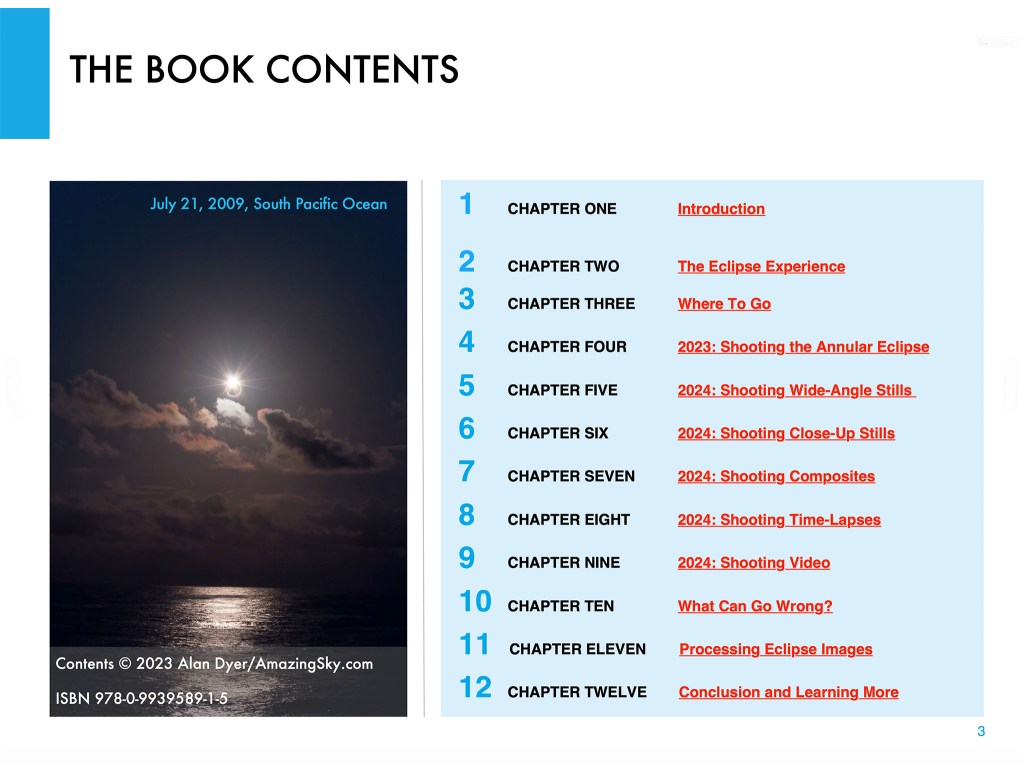

There are many ways to capture great images and movies of a total eclipse of the Sun. I outline them all in great detail in my 380-page ebook How to Capture the Solar Eclipses, linked to at right.

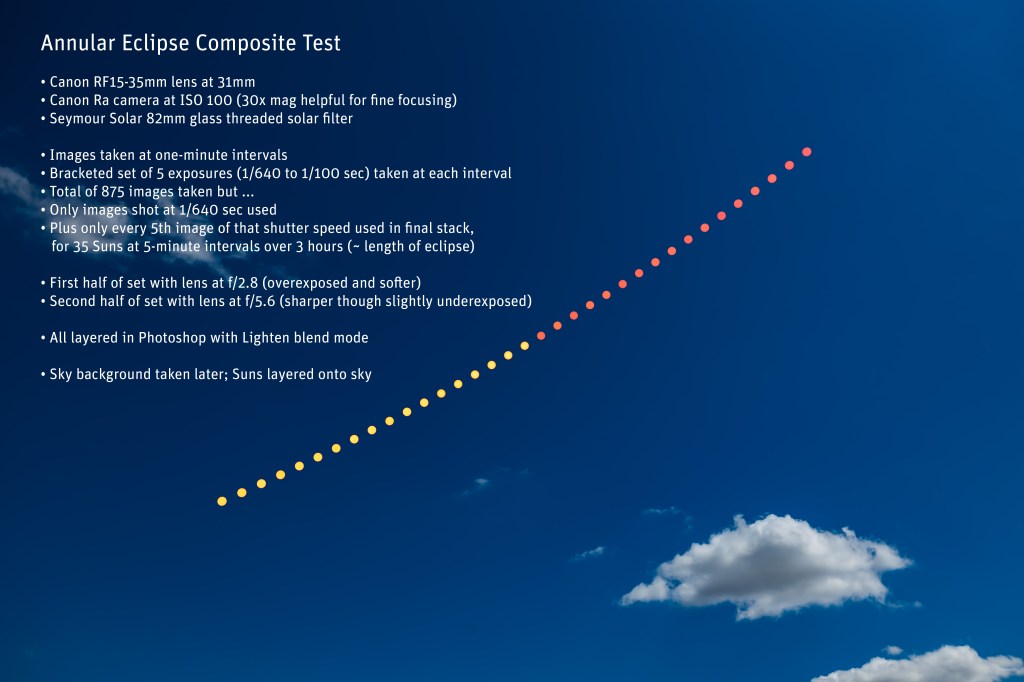

Originally published in June 2023, I revised the ebook following the October 14, 2023 annular eclipse of the Sun to include “lessons learned at the eclipse,” and some processing tutorials on assembling annular eclipse composites. I’ve also added new content on using software to control cameras and updated information about solar filters.

Brief Tips and Techniques

My breakdown of recommend methods, in order from simplest to most complex, and with increasing demands on your time, is generally this:

- Use a Phone Camera for a Movie. While they can be used for a quick handheld grab shot during totality, a better method is to place a phone on a tripod using a clamp of some kind. Then a few minutes before totality aim and frame the scene, with no filter over the camera lens. Start it in movie mode to record video of the eclipse and sky changes, and the excited sounds of your group! Just remember to stop the video shortly after the end of totality and aim the phone away from the Sun. Never leave any unfiltered camera aimed at the Sun for a long time.

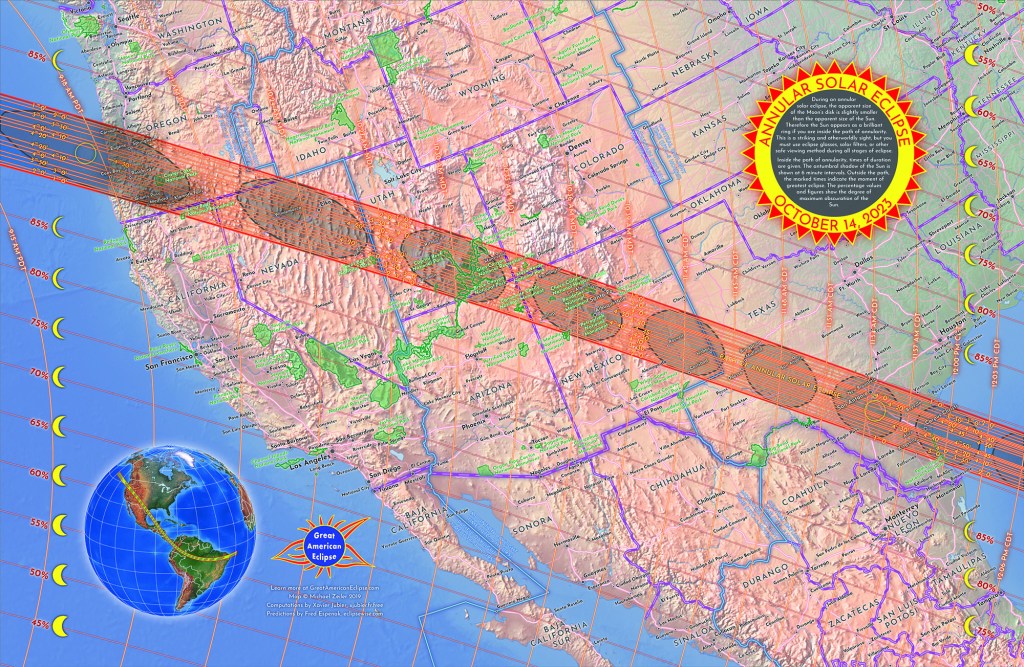

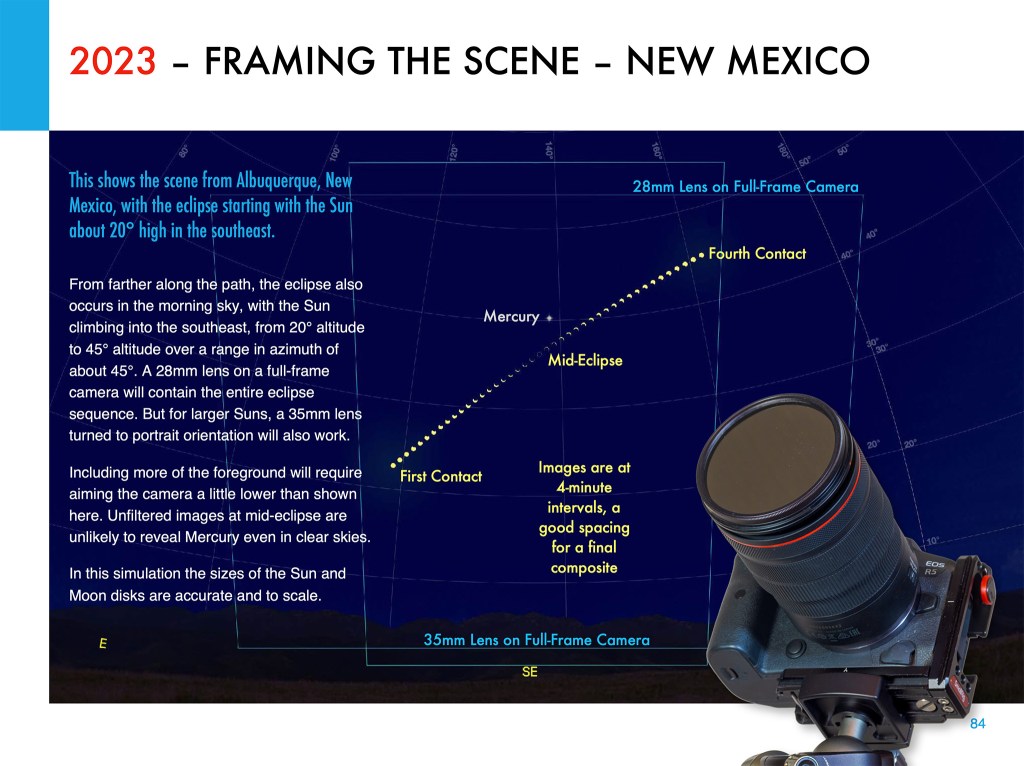

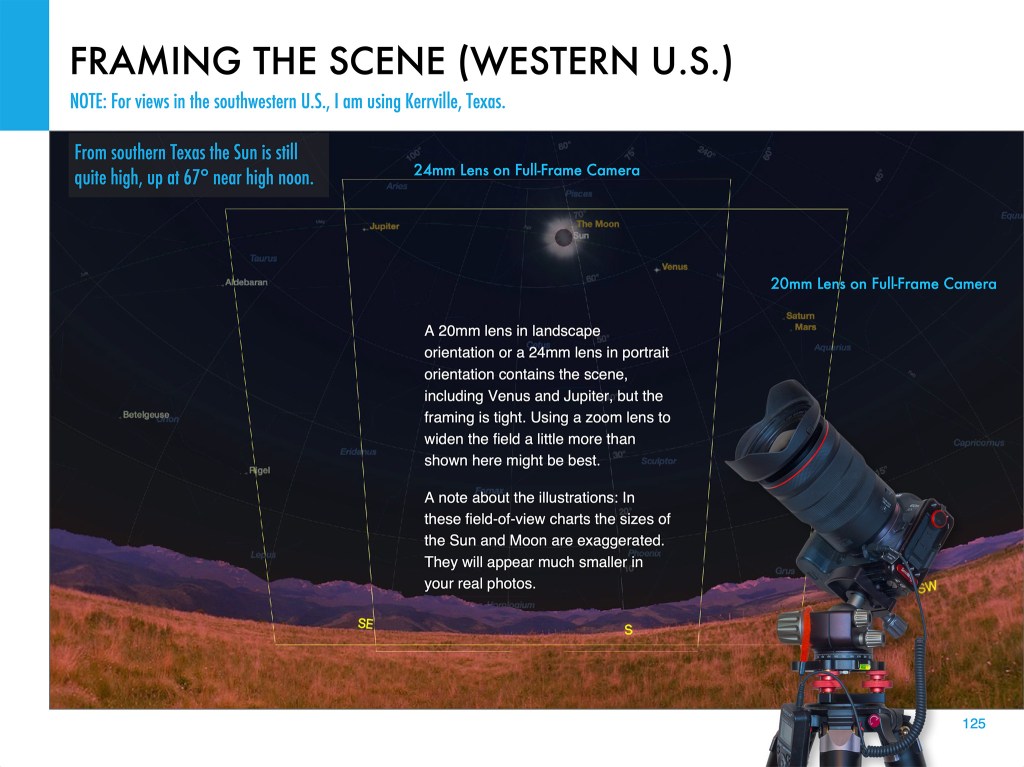

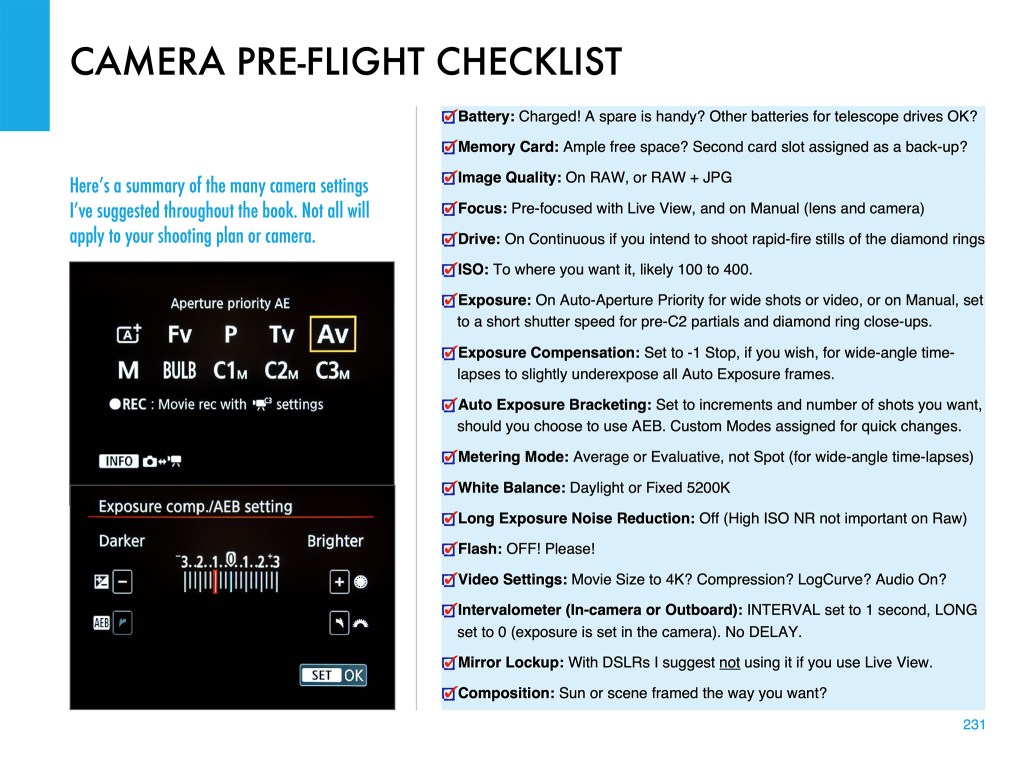

- Shoot a Wide-Angle Time-Lapse. Using a DSLR or mirrorless camera and a wide-angle lens (it might need to be as wide as a 14mm at sites in Mexico and the southern U.S.) aim and frame the camera to include the Sun and landscape below. Focus the lens! And leave it on manual focus. But put the camera into Auto-Exposure Aperture Priority (Av) with wide-area metering and with it set to underexpose by -1 EV Exposure Compensation. With the camera at ISO 100 or 200, use either its internal intervalometer (if it has one) or an external intervalometer to take frames once per second. Start the sequence with no filter on the lens a few minutes before totality. Let it run on its own until a few minutes after totality. The result is hundreds of frames you can turn into a time-lapse movie of the lunar shadow approaching and receding, and of the changes in sky colours. Or you can extract single frames at key points to process individually, as I did for the image above from August 2017. The advantage, as with the phone camera movie method, is that the camera, once going, requires no further attention. You can enjoy the eclipse!

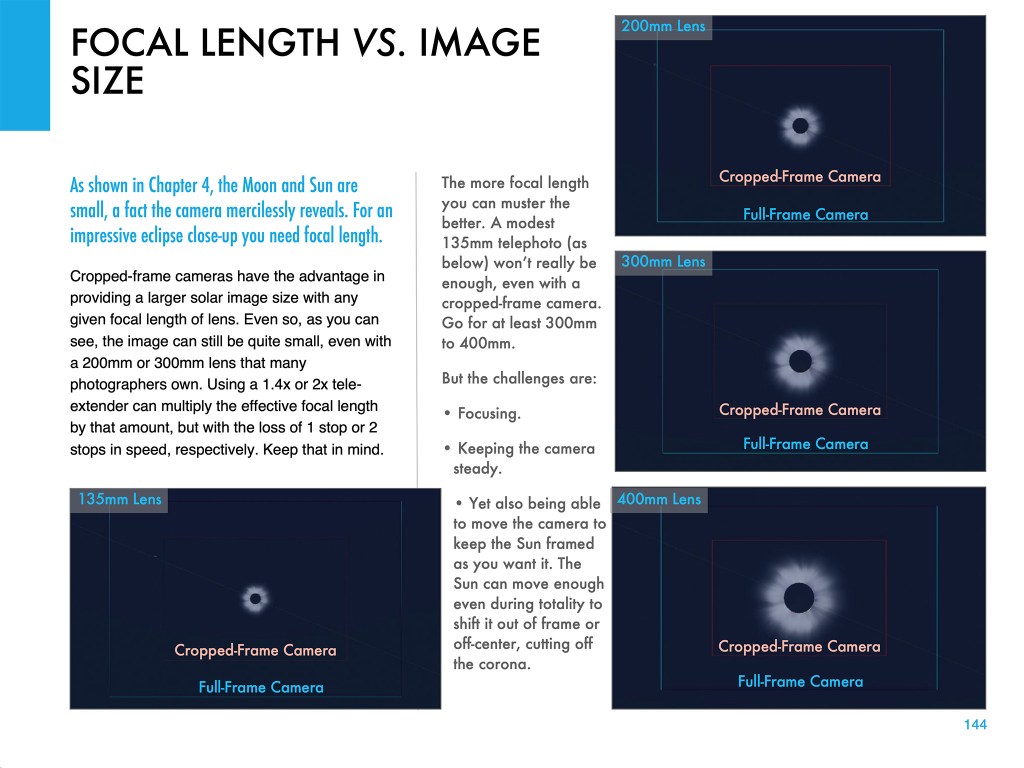

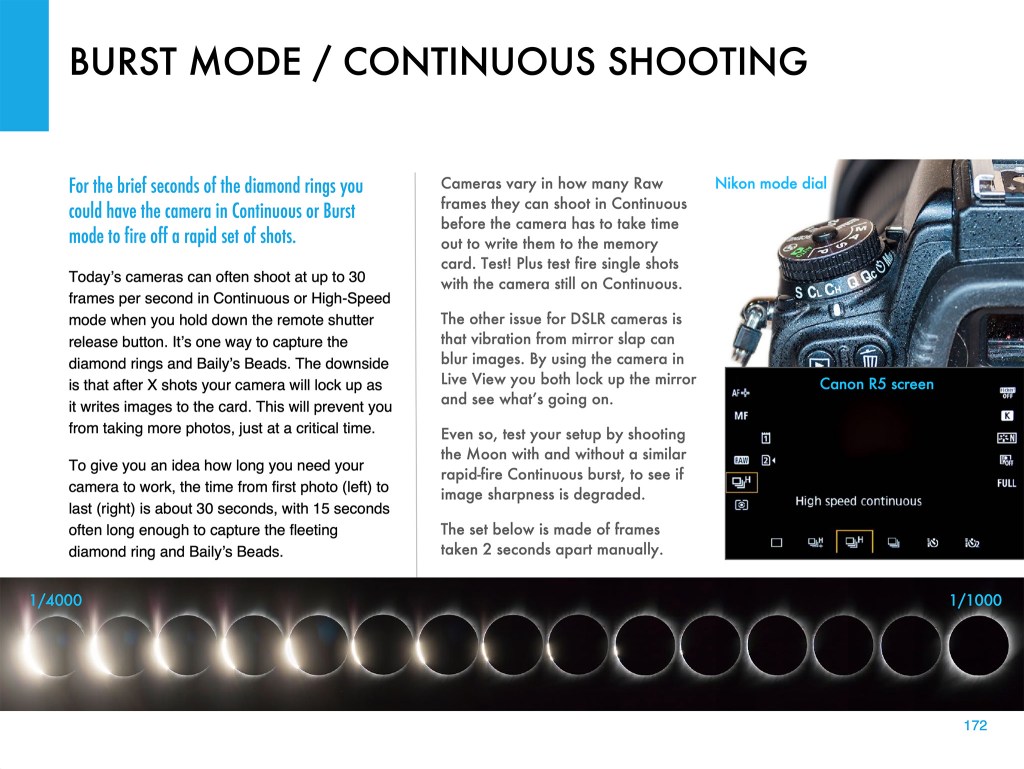

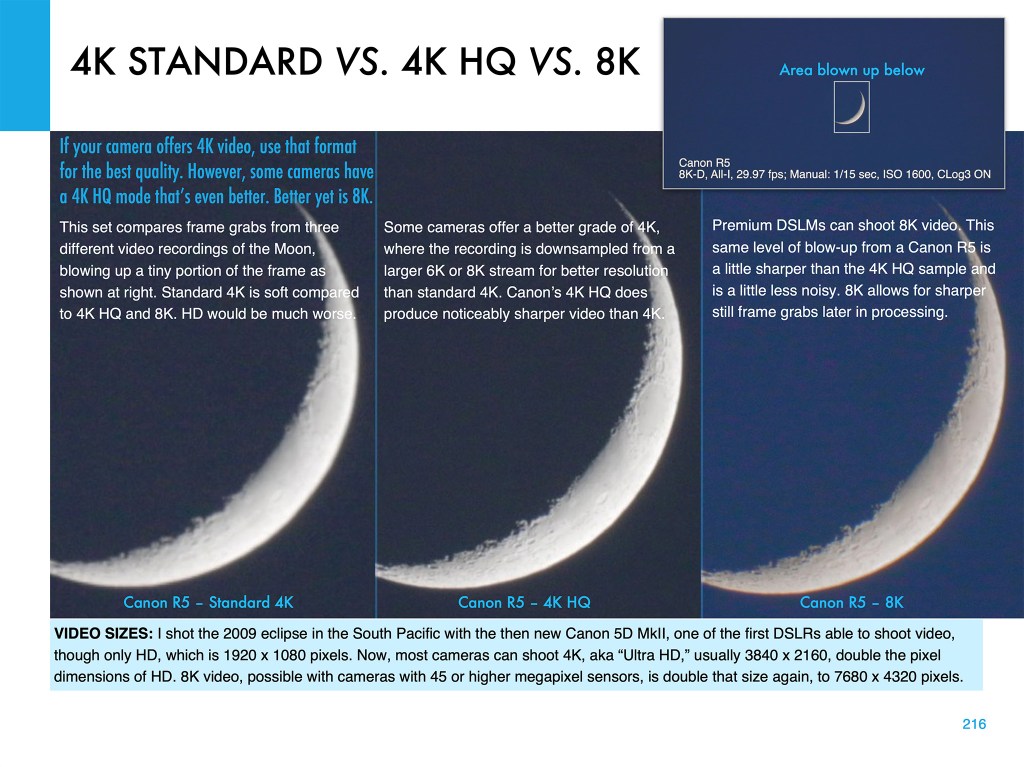

- Shoot a Telephoto Video. Use a 300mm to 500mm lens on a DSLR or mirrorless camera to shoot a real-time close-up video of the eclipse. Start the video a minute or two before totality with the Sun positioned to the left of frame centre and with a solar filter over the lens. Use a slow ISO, the lens wide open (typically f/4 to f/5.6) and the camera on Auto-Exposure Aperture Priority (Av). Just be careful to focus precisely on the filtered Sun before starting the video. Poor focus is what spoils most eclipse images, not poor exposure. Just before totality (about 30 seconds prior to Second Contact) remove the filter. The auto-exposure will compensate and provide a proper exposure for the rest of totality. Just let the camera run and the Sun drift across the frame from left to right. Just remember to replace the filter, or cap the lens, and stop the video shortly (~30 seconds) after totality and Third Contact. The video will capture the diamond rings and a well-exposed corona. Vary the exposure compensation during totality if you wish, but that involves more work at the camera. Otherwise, you can just let the camera run. But, as I illustrate in my ebook, it’s important to plan and place the Sun correctly to begin with (using a planetarium app to plan the sequence), so it does not drift off the frame or close to the edge.

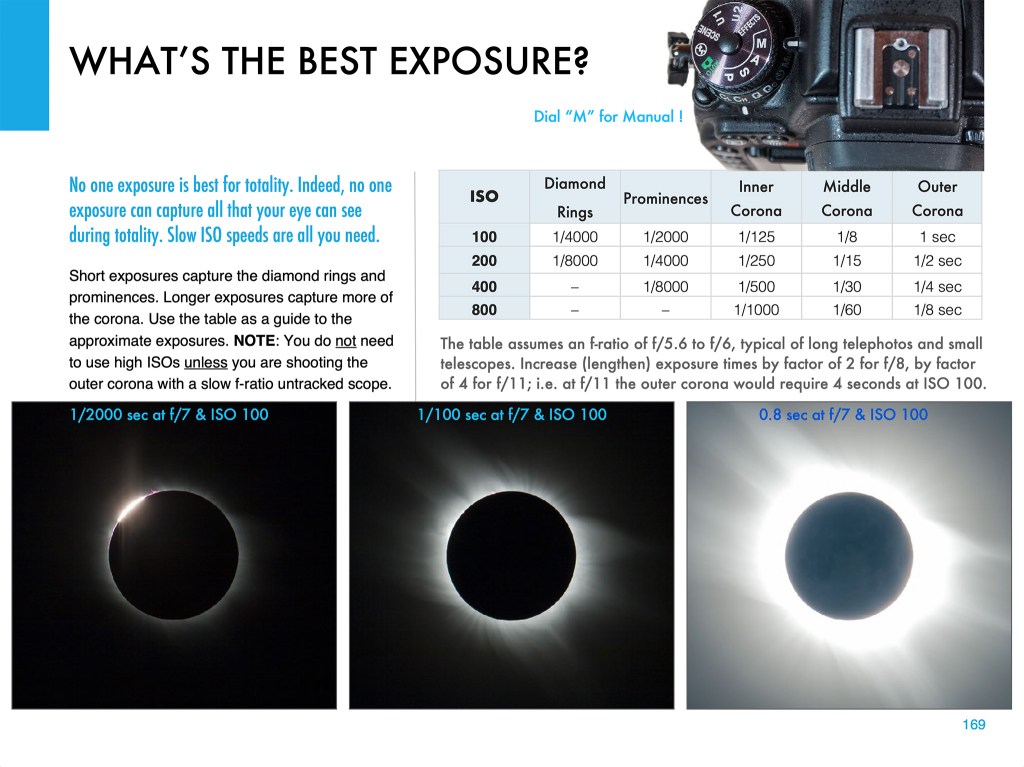

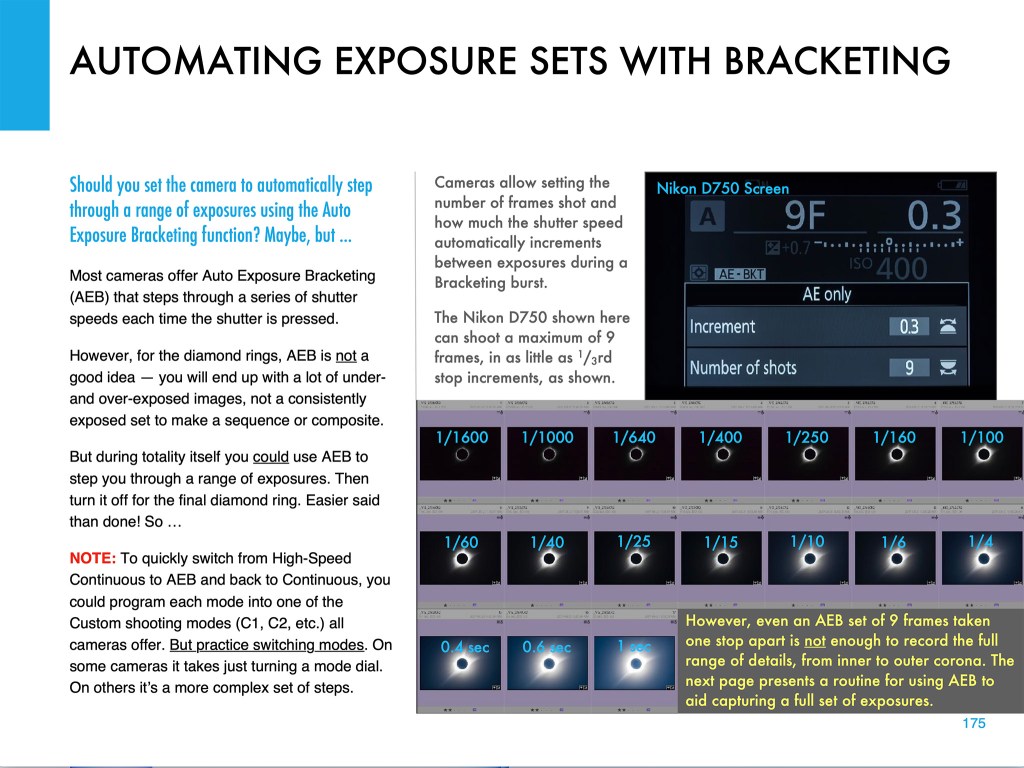

- Shoot Telephoto Close-Up Stills. Use the same type of gear to shoot still images. While you could shoot stills on Auto-Exposure, it’s better to shoot still images over a range of exposures, from very short (~1/1000 second) for the diamond rings and prominences, to long (~1 second) for the outer corona. No one exposure can capture all that the eye can see during totality. This takes more work at the camera, and with the camera on a static tripod you might have to re-centre the Sun during totality, another thing to fuss with and where things can go wrong. Using the camera’s Auto-Bracketing mode can help automate the shooting, allowing the camera to automatically shoot a set of 7 to 9 exposures at say, one-stop increments in quick succession with just one press of the shutter button (by using the self-timer set to 2 seconds).

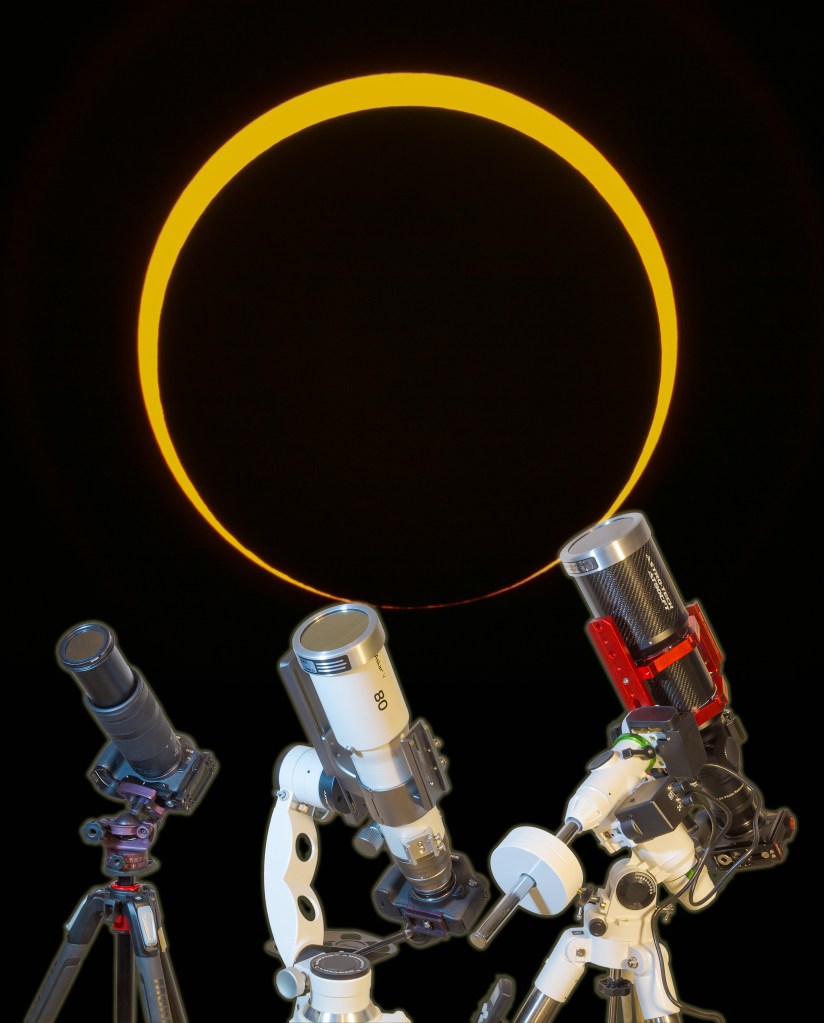

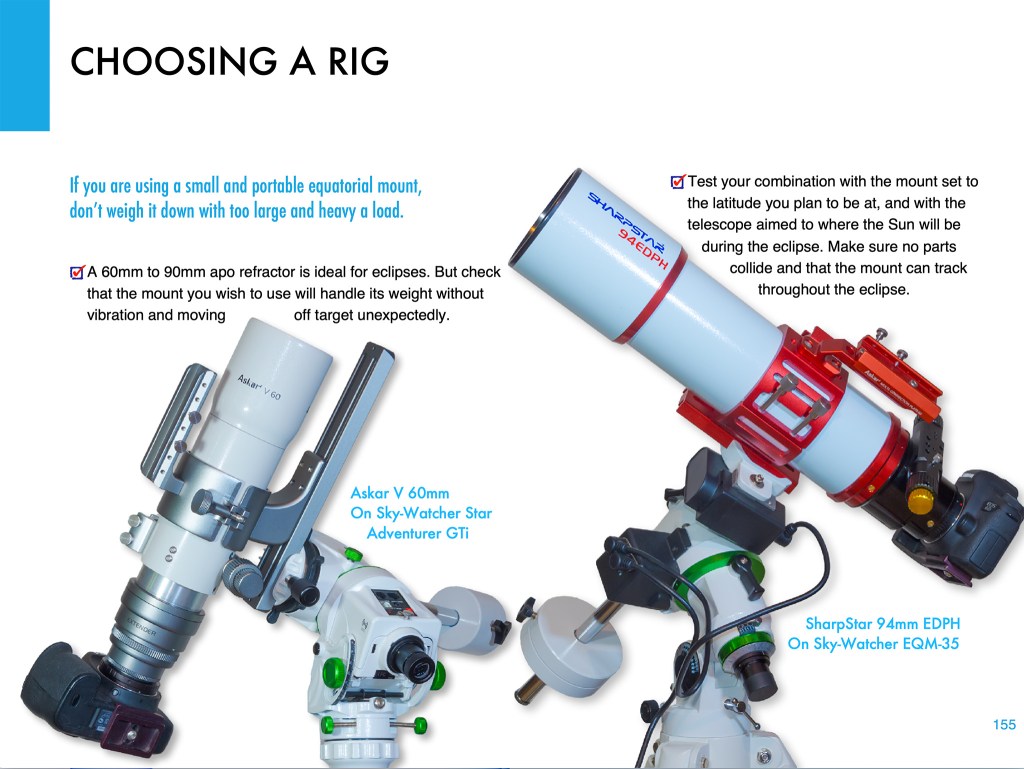

- Shoot with a Telescope on a Tracking Mount. Telescopes (I like 60mm- to 100mm-aperture apochromatic refractors) allow longer focal lengths, though I would advise against shooting with any optics longer than 600mm to 800mm, so the image frames the corona well. Use similar settings as above, but with the telescope (or a telephoto lens) on a tracking mount to turn from east to west at the same rate as the sky moves. That will ensure the Sun stays centred on its own, provided you have at least roughly polar aligned the mount. (Set it to your site’s latitude and aim the polar axis as due north as you can determine from compass apps.)

Those are brief summaries of the methods I recommend, as they are ones I’ve used with success in the past and plan to use on April 8. My ebook contains much more information, and answers to most of the “But what about using ….?” questions. And I provide lots of information on what can go wrong! Some learned the hard way over 16 previous total solar eclipses.

Video Tutorials

For a video tutorial, check out the webinar I conducted as part of the Kalamazoo Astronomical Society’s excellent Eclipse Series here on YouTube. It is about a 1-hour presentation, plus with lots of Q&A at the end.

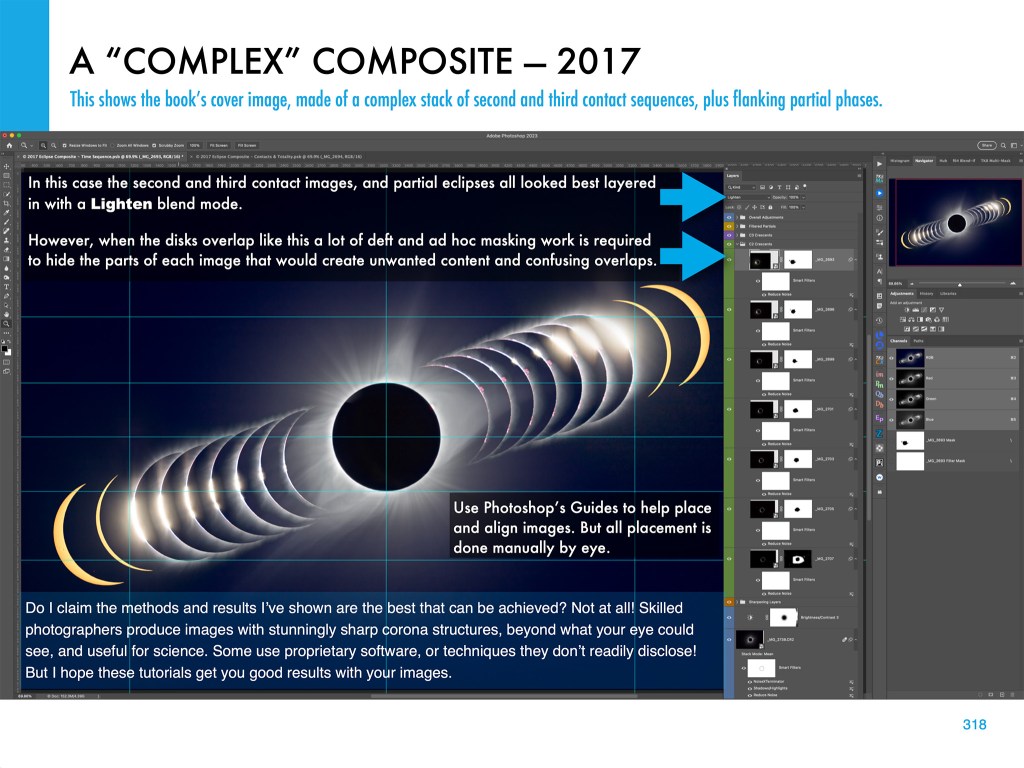

Of course, once you have all your images, you need to process them. My ebook’s biggest chapter (at 80 pages) is the one on processing still images and time-lapses.

So, a month after I presented the above webinar on Shooting, I was back on-line again for a follow-up webinar on Processing. You can view that KAS Eclipse Series tutorial here on YouTube.

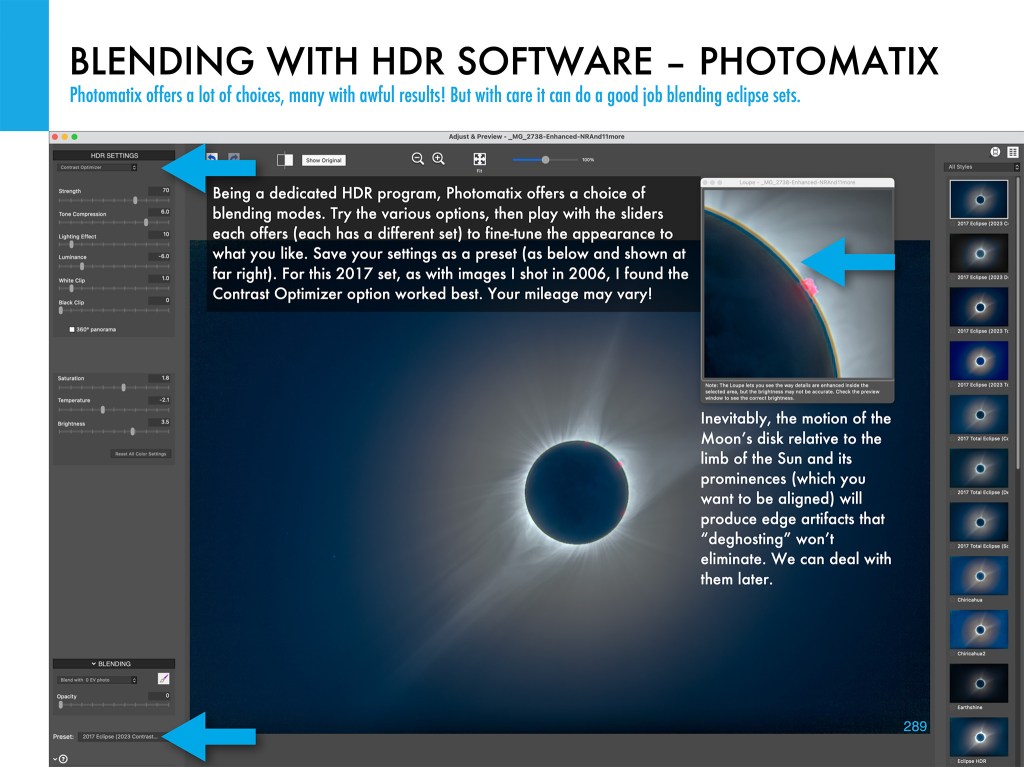

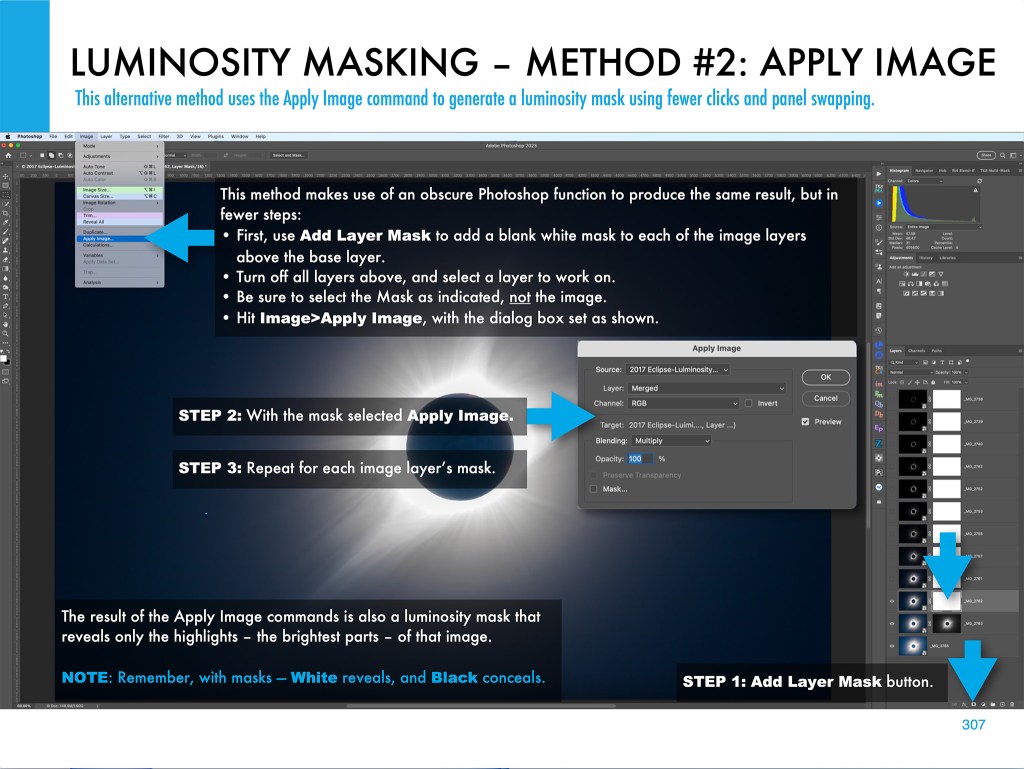

I cover processing single wide-angle images, a wide-angle time-lapse series, single-image close-ups, and blending multiple exposure composites.

A month later, I presented a further webinar to the Astronomical League as part of their AL Live series, again on shooting the eclipse, but now with an emphasis on techniques amateur astronomers and astrophotographers with typical telescope gear might use.

You can view the AL Live webinar here. My presentation begins at the 44-minute mark.

I emphasized that the kinds of gear astrophotographers use these days with great success on deep-sky objects might not work well for the eclipse. The specialized cameras, and software used to control them, are just not designed for the demands of a total eclipse, where exposures have to range over a wide array of settings and change very quickly. Images have to be taken and recorded in rapid succession.

I suspect a lot of ambitious and overly-confident astrophotographers will come away from the 2024 eclipse disappointed — and what’s worse, without having seen the eclipse because they were too wrapped up looking at laptop screens trying to get their high-tech gear working.

Practice, Practice, Practice

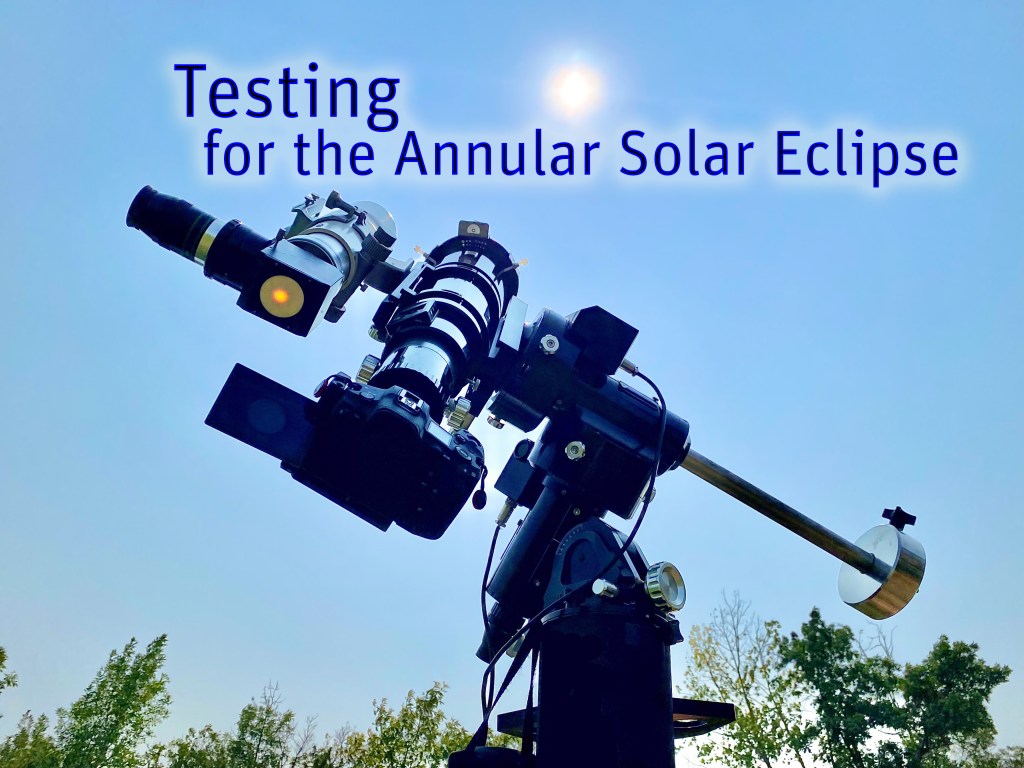

In these webinars and in my ebook, my common theme is the importance of practicing.

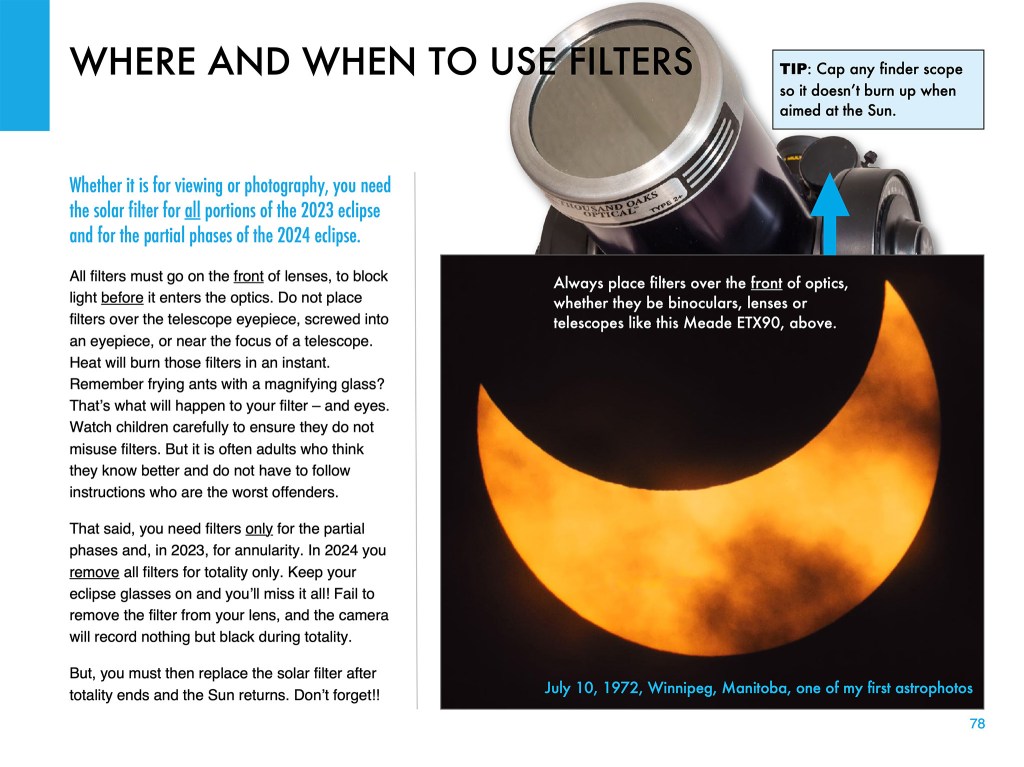

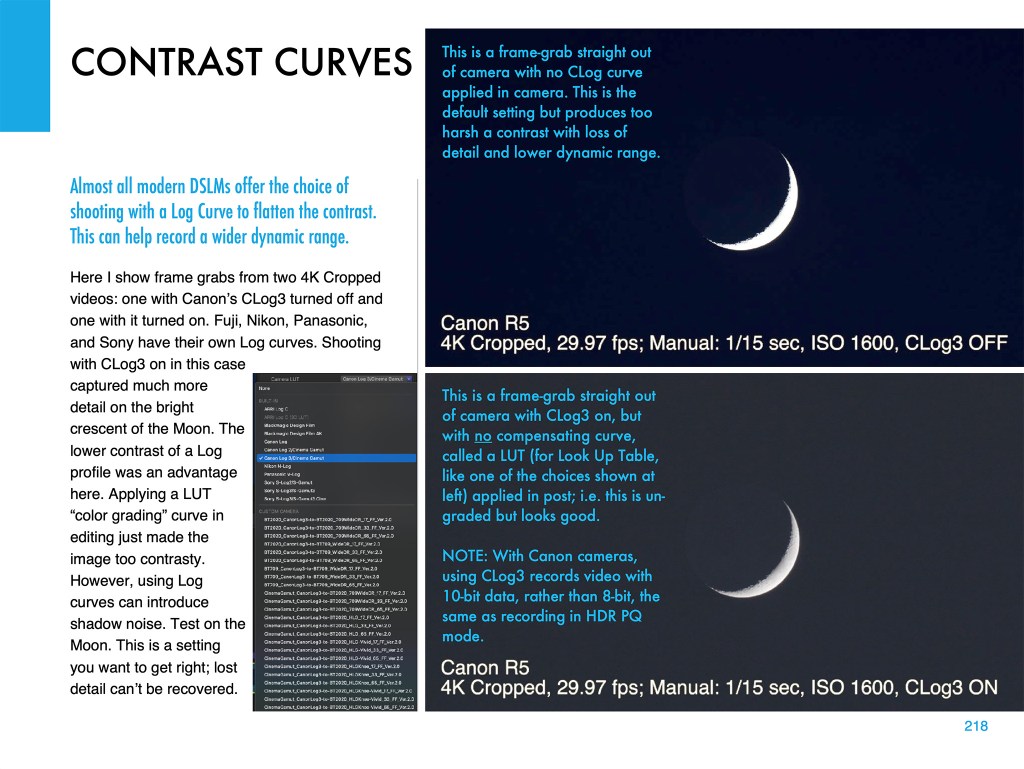

Don’t assume something will work. Practice with the gear you intend to use, on the Sun now (with proper filters) and on the Moon. The crescent Moon, with dim Earthshine lighting the lunar night side, is a great practice target because of its wide range of brightness. And it moves like the Sun will, to check maximum exposure times vs. image blurring from motion.

Practice with your tripod or mount aimed to the altitude and location in the sky where the Sun will be from the site you have chosen. Set a tracking mount to the latitude you will be at to be sure it will aim at and track the Sun without issues. Some telescope mounts stop tracking when they reach due south, exactly where the Sun will be at totality from southern sites. That’s a nasty surprise you do not want to encounter on eclipse day.

All this and much more is covered in my ebook, available for Apple Books and as a PDF for all platforms here from my website at https://www.amazingsky.com/EclipseBook

Good luck on eclipse day!

— Alan, February 21, 2024