Join me in a guided tour of the famous (and not so well known!) constellations of the northern spring sky.

The northern spring sky lacks the splendour of bright patterns such as winter’s Orion or summer’s Cygnus, but it is still well worth getting to know. The Milky Way is out of sight, and in its absence we are left with fewer bright stars to dazzle us at night. But we are treated to the year’s best views of famous constellations such as Ursa Major, Leo and Virgo.

Now, I am talking about the sky of the northern hemisphere, where April and May brings spring, and places the Big Dipper high overhead. While some of these constellations can be seen from the southern hemisphere, they appear to the north, low and “upside-down” from the views I present here. And April and May are autumn months.

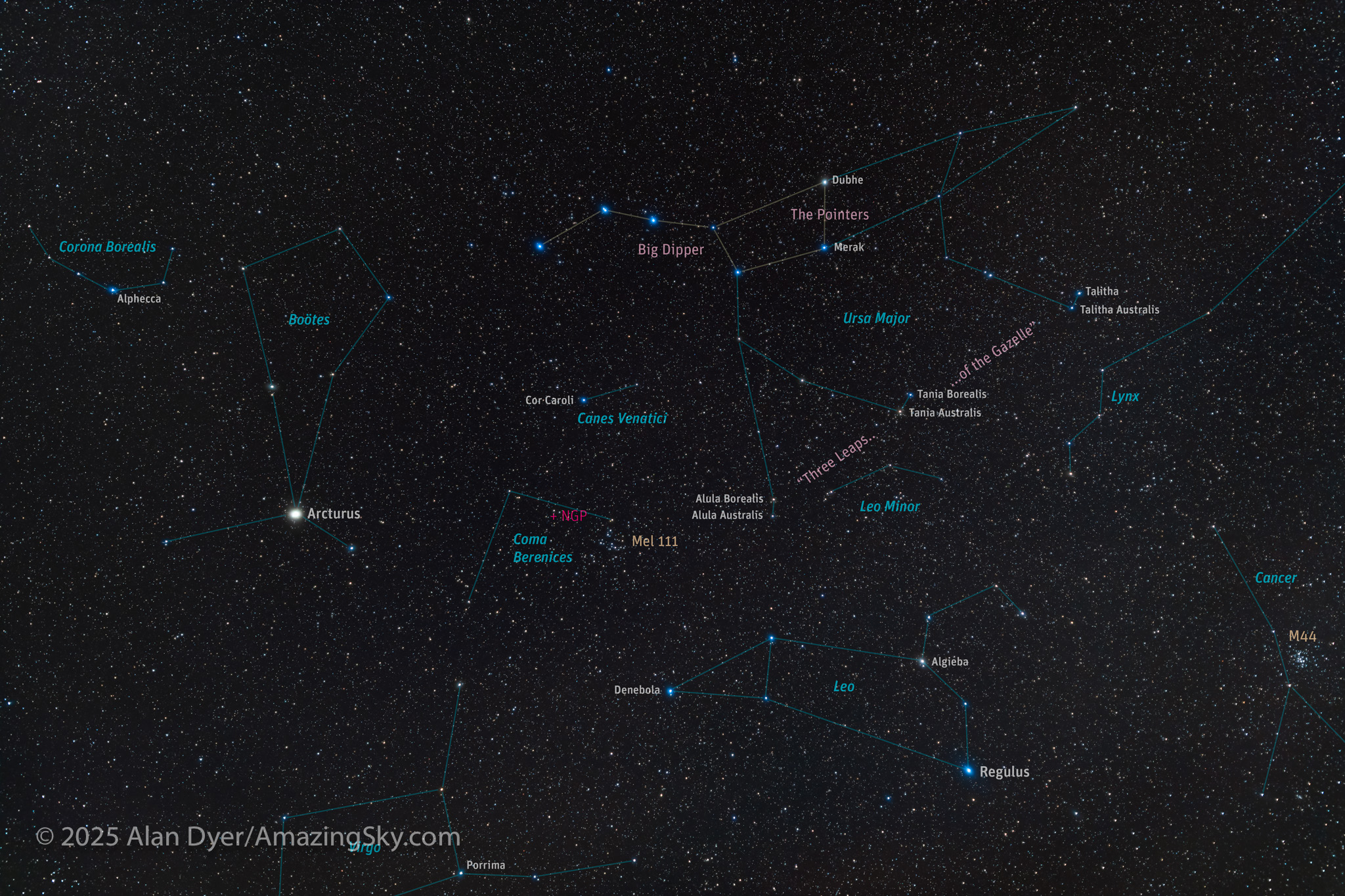

Let’s start with the “big picture.” (Tap on images to bring them up full screen.)

NOTE: I shot all these images during a run of fine nights in mid-April 2025 with a 15-35mm zoom lens on a Canon EOS R camera, and on a Star Adventurer tracker. Separate exposures through a Tiffen Double Fog 3 filter added the star glows.

This image, in labeled and unmarked versions, presents a wide view of the spring sky from horizon to well past the zenith overhead. The key pattern to look for is the Big Dipper, at its highest in northern spring. In the UK and Europe it is known as the Plough or Wagon. Look way up to find it first.

Its Pointer Stars in the Bowl famously point north to Polaris. But here I show the other pointer line off the Bowl, to the south, to Leo the Lion. It is well known as one of the constellations of the Zodiac. Leo is marked by one of the brightest spring stars, Regulus.

Use the Handle of the Dipper to arc downward, to locate the brightest star of spring, Arcturus, shining with a yellow light. Keep that line going south and you’ll come to a dimmer and bluer star shining in the south. That’s Spica, the brightest star in Virgo, the Zodiac constellation east of Leo.

Now let’s take a closer look at selected areas.

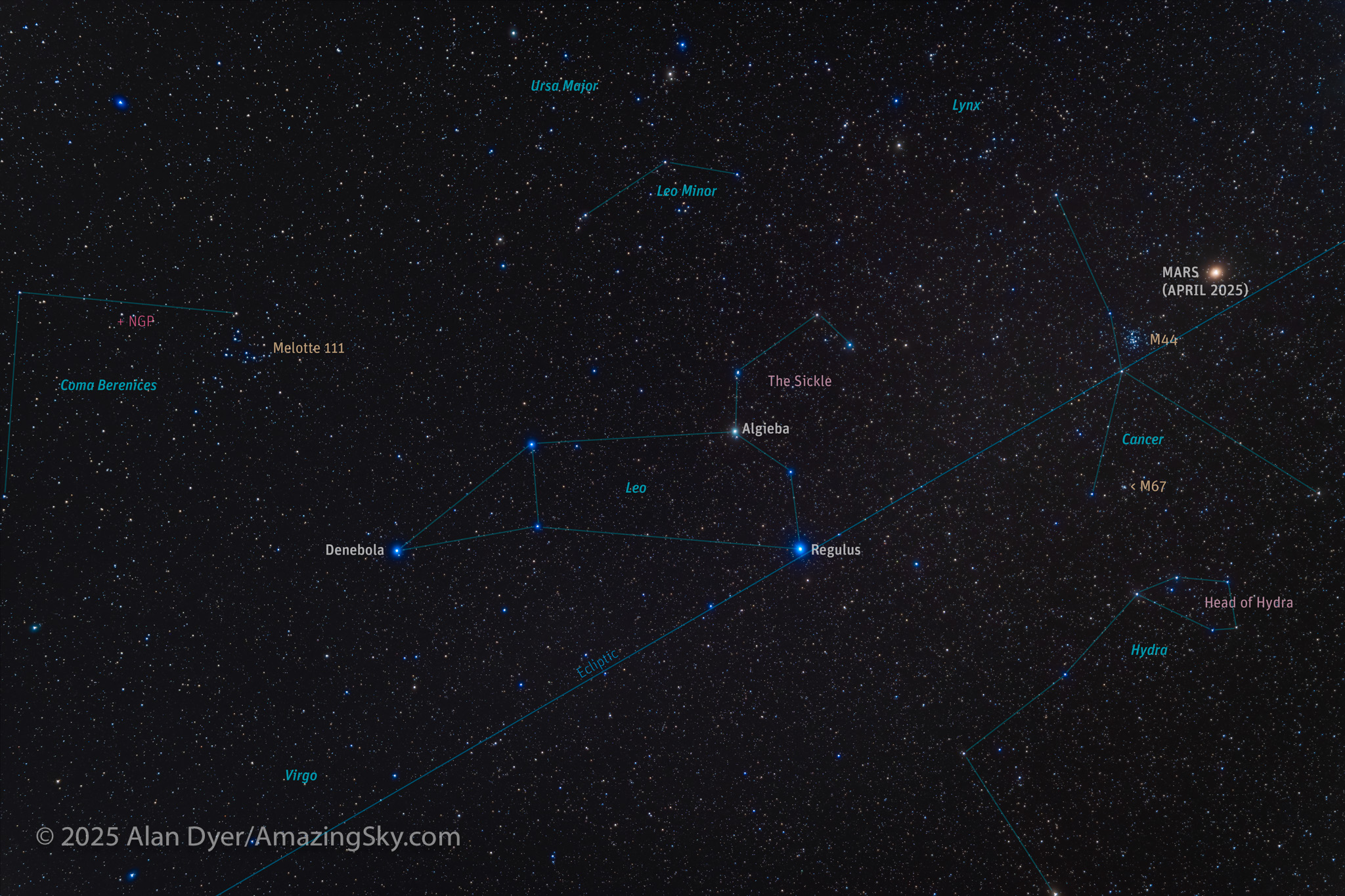

This is still a wide view, looking up and high in the south. There’s the Big Dipper/Plough at top. It is not a constellation. It is an “asterism” of seven stars within the large constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear. With a little imagination you can join the dots to make a bear (many northern cultures did so). Except we draw him with a long tail, which bears do not have!

The paws of the Bear are marked by a trio of double stars: Alula Borealis and Australis, Tania Borealis and Australis, and Talitha and Talitha Australis. The names come from Arabic words for “first,” “second,” and “third” as these sets of double stars are collectively called the Three Leaps of the Gazelle in Arabic sky lore. Once you see them you’ll be surprised at how distinctive they are.

Below Ursa Major is Leo, a pattern that does look a little like a sitting cat. Its bright star Regulus was named by Copernicus, from a Latin word for “little king.” But Regulus has long been known as the heart of the Lion.

To the east lies brighter Arcturus, a name that means “bear watcher,” as it and its host constellation Boötes, the Bear Herdsman, are tied to Ursa Major and Minor in Greek mythology.

Here I frame Leo, but also two of the constellations that flank him: Cancer the Crab to the right (or west) and Coma Berenices to the left (or east). Each contains a bright naked eye cluster of stars:

- Messier 44 or the Beehive cluster in Cancer, the faint Zodiac pattern west of Leo. When I shot this image in mid-April 2025 red Mars was just entering Cancer.

- and Melotte 111 in Coma Berenices. At one time this clump of stars easily visible to the naked eye was considered part of Leo, as the tuft on the end of his tail. The area was broken off as its own constellation in the 3rd century BCE, and named for Queen Berenice of Egypt, and for her legendary hair (“coma”).

- Together, the obvious pattern of Leo and the star clusters that flank him form one of the spring sky’s most notable sights.

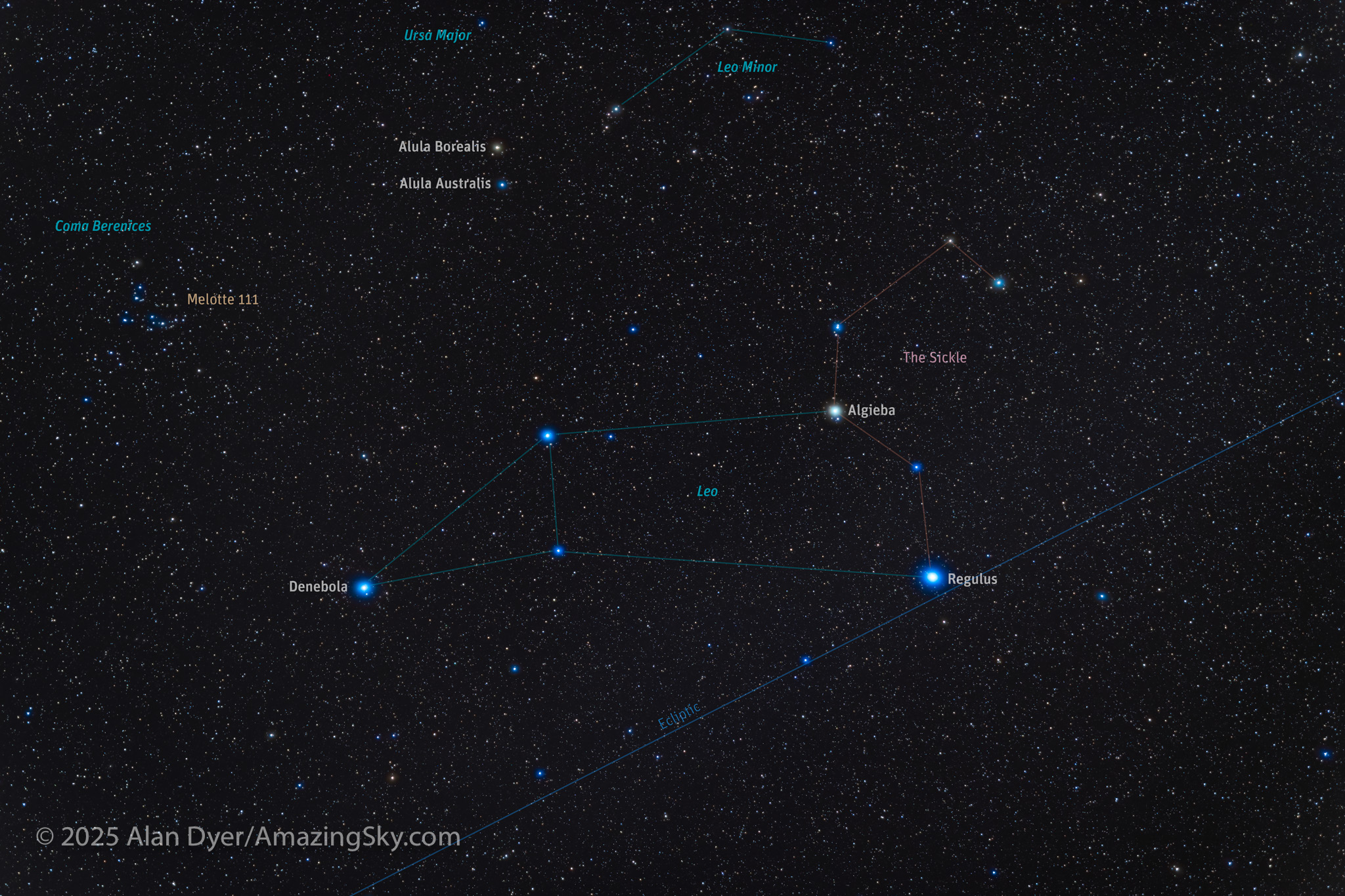

The head of Leo is marked by a curving arc of stars popularly called The Sickle. Or it is thought of as backwards Question Mark, with Regulus the dot at the bottom. Leo is one of the oldest constellations, as there are records of this pattern dating back to 4000 BCE in Mesopotamia.

More modern is the obscure pattern above it, Leo Minor, the Little Lion. It was invented by 17th century star chart maker Johannes Hevelius, to fill in a blank area of sky. Even in a dark sky, it is tough to make out its innocuous pattern between Leo and Ursa Major.

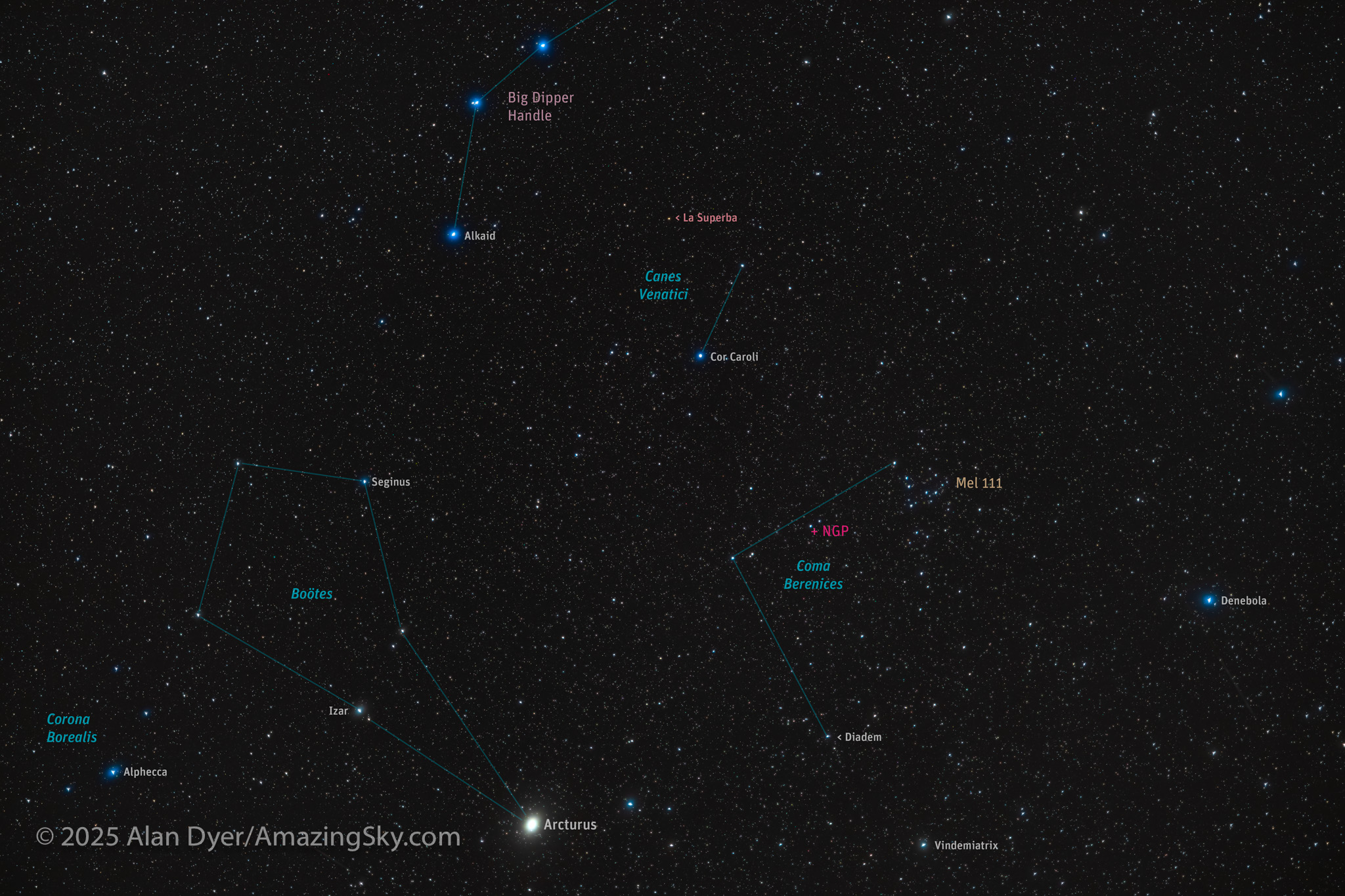

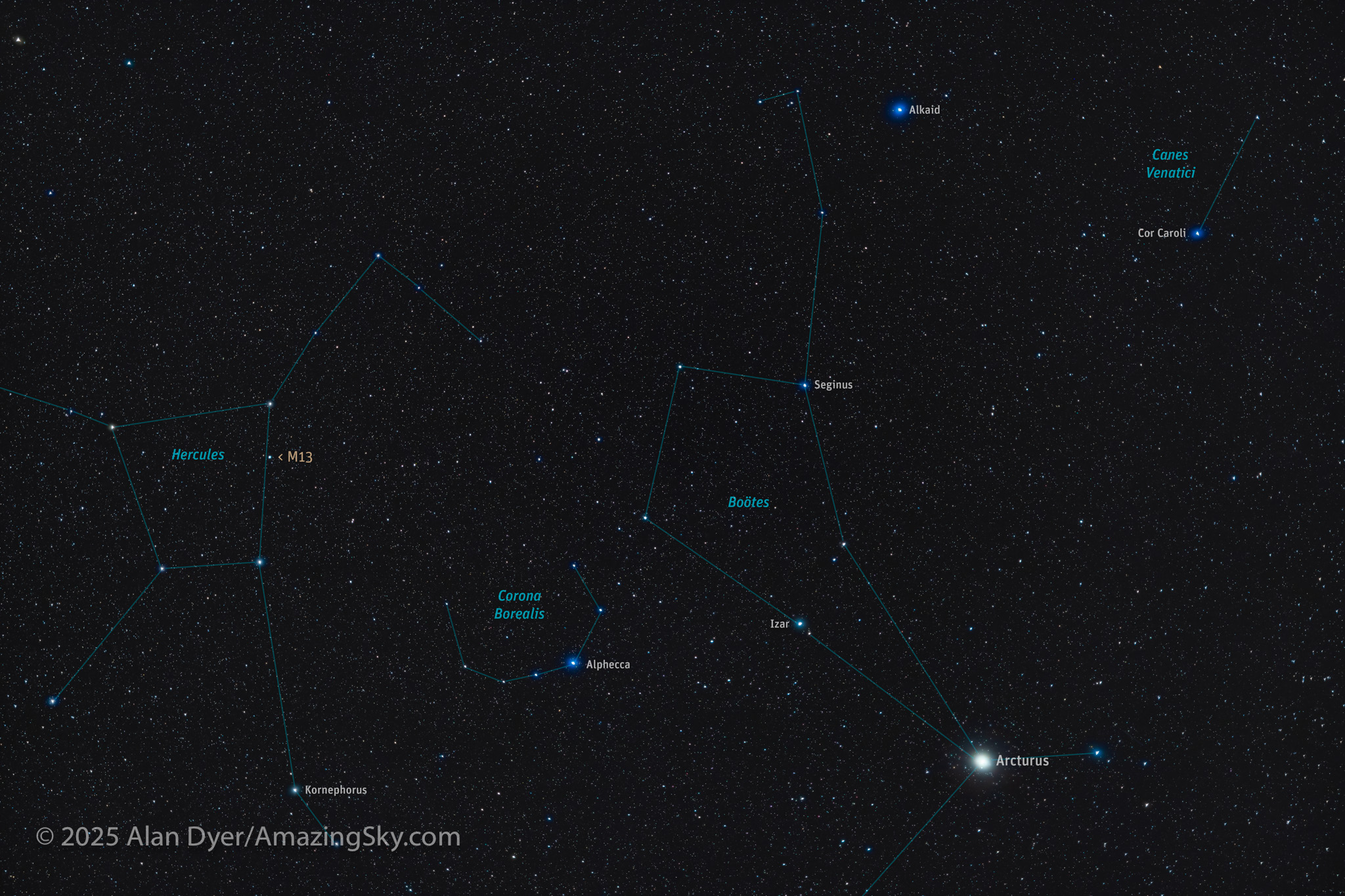

Another obscure pattern created by Hevelius lies below the Handle of the Big Dipper. A sparse pattern of stars marks Canes Venatici, the Hunting Dogs that belong to Boötes to help him herd bears! While not much to look at with the naked eye, Canes Venatici does have superb targets for telescopes, such as the double star Cor Caroli and very red star La Superba.

Below the Dogs lies Berenices’ Hair, home to the star cluster Mel 111, but also the North Galactic Pole (NGP). This is the point 90º away from the plane of the Milky Way and the Galactic Equator seen in our winter and summer skies. But in spring we look straight up out of our Galaxy, to many other telescopic galaxies that inhabit Coma and Virgo, our next stop.

Below Leo and Boötes lies the Zodiac pattern of Virgo, usually thought of as the reclining Greek goddess of agriculture and the harvest. Spica is easy to see, but the sprawling pattern of the rest of Virgo is not so obvious. It takes a dark sky to pick out the other fainter stars of the goddess.

Easier to see, despite its low altitude from northern latitudes (it skims my horizon), is the quadrilateral pattern of Corvus the Crow, a constellation that dates from the 2nd century CE and the star catalogue of Ptolemy. The Crow sits on the tail of Hydra the Water Snake, a long zig-zag line of stars that is only partly contained here. The head of Hydra, off frame to the right here, is in the earlier image of Leo and Cancer.

Another pattern riding the back of Hydra is Crater the Cup, associated with Corvus and Hydra in a Greek myth in which the Crow is sent to fetch water for Apollo but fails. Apollo flings the Crow, Cup and Snake into the sky. Angering the gods could get you immortalized in the sky!

Heading back north above Virgo, we return to the kite-shaped pattern of Boötes above Arcturus, the brightest star in the northern half of the sky. Coming up later on spring evenings, and to the left is a semi-circle of faint stars, the Northern Crown, or Corona Borealis, another of Ptolemy’s patterns from the 2nd century. The crown belongs to the princess Ariadne.

Astronomers have been watching Corona Borealis closely in recent months, waiting for a recurrent nova star to explode and add a new jewel to the Crown. So far, no luck. T CorBor remains stubbornly dim.

To the east of Corona is the H-shaped pattern of Hercules, the Roman name for the Greek hero Heracles. Among his many labours and conquests, he slewed Cancer the Crab and Leo the Lion.

Returning down south and scraping the horizon from my northern latitude late on spring nights are the next two constellations of the Zodiac east of Virgo: Libra the Scales and Scorpius the Scorpion.

Libra is a faint pattern but with the wonderfully named stars Zubeneschamali and Zubenelgenubi, meaning the northern and southern claws, as these stars were once considered part of the Scorpion. However, Libra has long been seen as a balance or scales for meting out justice. It is the only Zodiac constellation that is an inanimate object.

Scorpius is one of the few patterns that looks like what it is supposed to be, though here I see only the northern part of the constellation. His curving tail has yet to rise as the Milky Way comes into view low in the south just before dawn this night. The bright orange star is Antares, the heart of the Scorpion, set in an area rich in dark and colourful nebulas.

The appearance of Scorpius signals the return of the Milky Way to the sky, and the rise of the summer constellations.

But no astronomical life is complete without getting to know the patterns of spring. Clear skies and happy stargazing!

— Alan, April 30, 2025 (amazingsky.com)