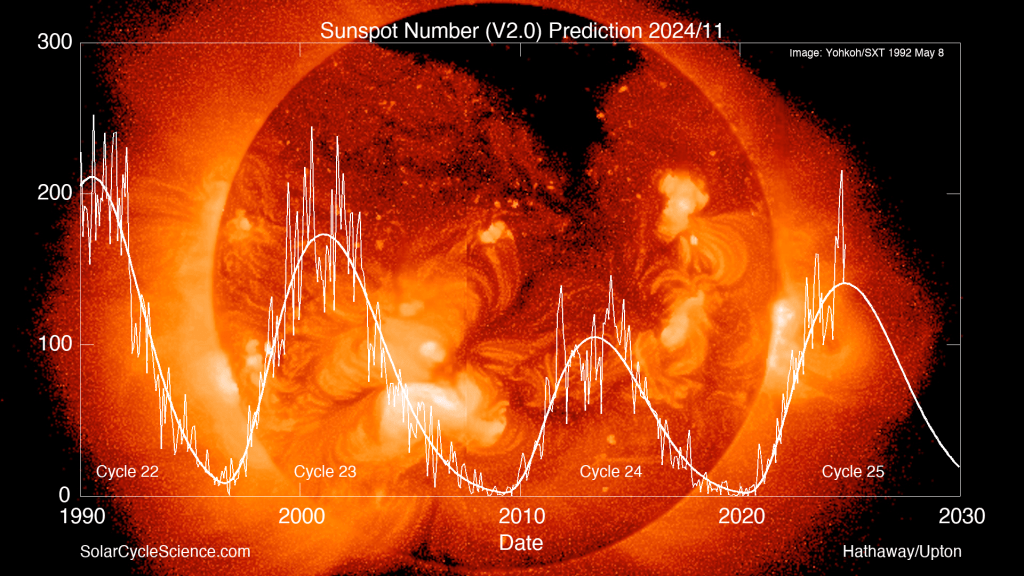

The Sun peaked at “solar maximum” and gave us wonderful sky shows in 2024.

Officially, the Sun reached the peak of its roughly 11-year cycle of activity — “solar max” — in late 2024. That’s according to NASA and NOAA.

During 2024 several major solar storms erupted as a result of the Sun’s increased activity. They blew massive clouds of energetic particles — electrons and protons — away from the Sun. Some of those storm clouds swept past Earth, sparking bright auroras widely seen in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

I was fortunate enough, as many were, to witness several of 2024’s great auroras, from home in Alberta, and from as far south as Arizona.

Trips north to Churchill, Manitoba, and to northern Norway also presented some fine aurora nights. But that’s normal at any time in the solar cycle from those sub-Arctic and Arctic locations.

It’s when the aurora comes to you that you get a truly memorable show. And 2024 had its share of them.

NOTE: My blog has a lot of images and links to movies that may take a while to load. Images can be clicked on to bring them up full screen. The blog also contains many links to other sites to learn more!

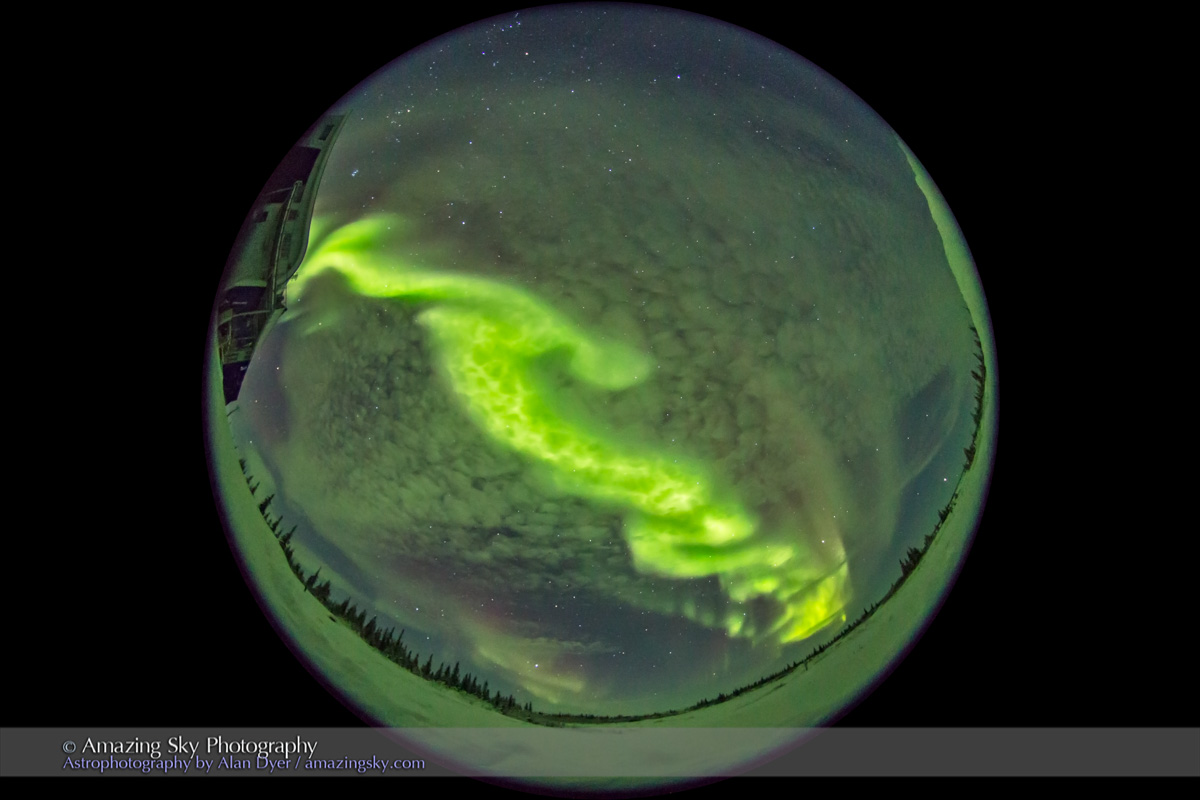

Starting the Year — February in Churchill

This was the month I made my annual trek to Churchill, Manitoba, to instruct aurora tour groups at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre. Why not join us in 2025?

Yes, the air is cold (usually about -25° C) but the skies are often clear and aurora filled, as Churchill sits under the normal location of the auroral oval, the main zone of auroras. In fact, it is as far south in the world as the auroral oval normally resides, at a latitude of only 58º North, well south of the Arctic. If it’s clear, there’s almost always some level of Northern Lights.

This year, 2024, was no exception. Even on nights with low readings on the usual auroral indicators we got sky-filling displays that are rare down south.

What I find in Churchill is that even with numerically weak and visually dim shows, as above, the camera often sees very red and photogenic auroras. The eye sees the colours only when the aurora brightens, which it often does (as I record below), sparking rippling green curtains (from glowing oxygen) fringed with pink (from glowing nitrogen).

I didn’t shoot time-lapses or movies this year in Churchill. Instead, the example movie above, shot using just real-time (not time-lapse) videos, is from February 2019. It is from my AmazingSky YouTube channel.

The video presents the aurora much as the eye saw it, and as it appears when it dances.

However, I tend now to shoot mostly panoramas, as above, from this year’s visit. They can take in the full show across the sky, in high-resolution images suitable for framing!

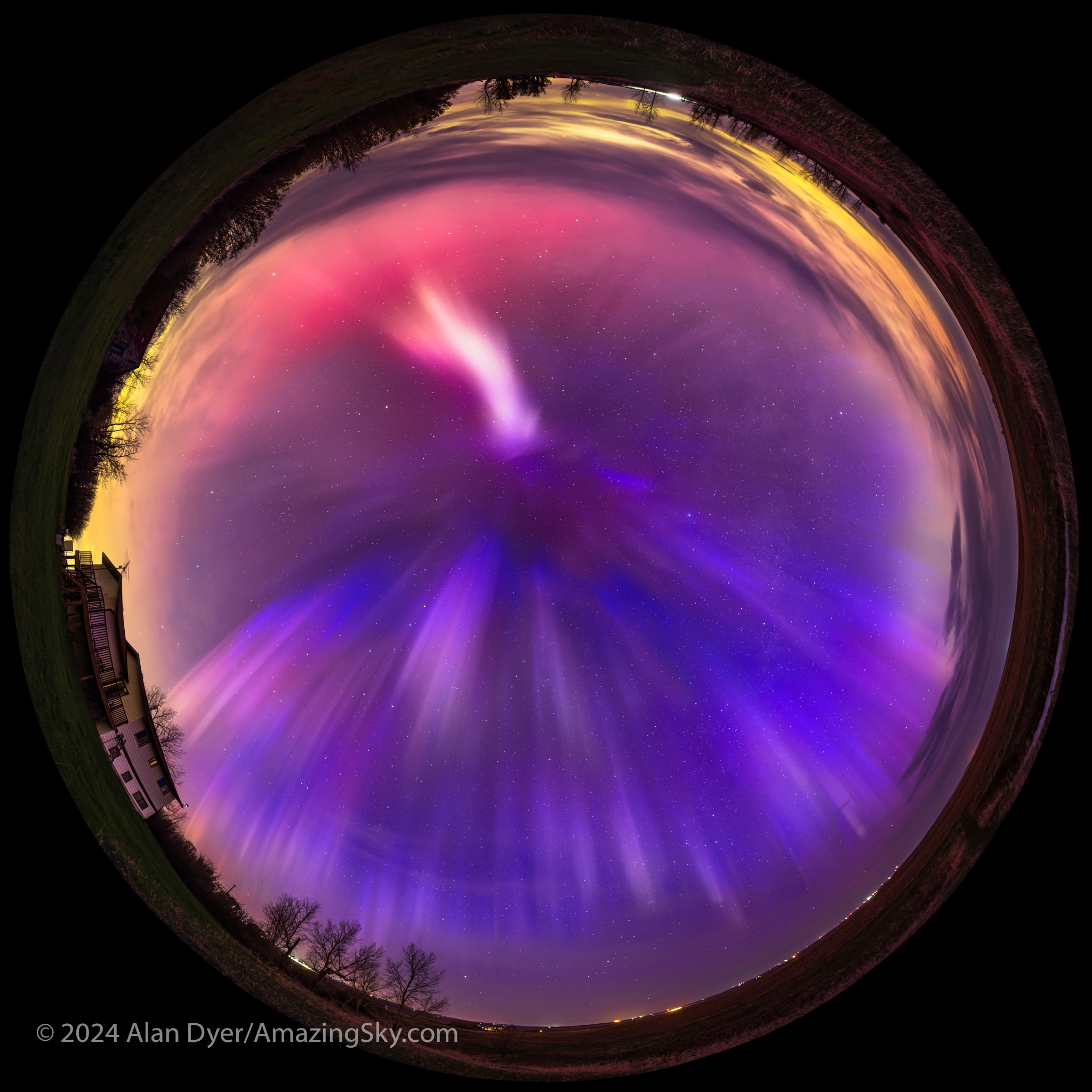

May 10 — The Great May Display

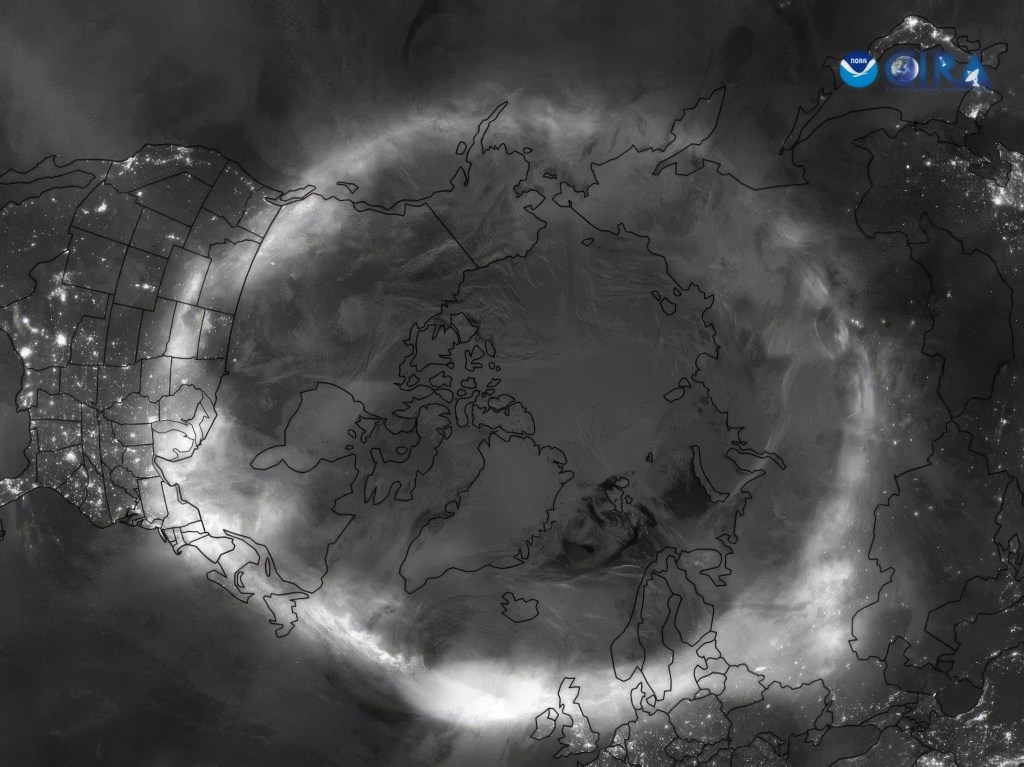

The aurora apps were beeping this day, warning a great display was in the offing. The composite satellite image below from NOAA shows the actual extent of the aurora around the Northern Hemisphere during the great display of May 10/11 .

Note how the auroral oval is indeed an oval and how the centre is not the geographic North Pole. It is the North Geomagnetic Pole, in the High Arctic of Canada. 🇨🇦 So the oval dips down farther south over North America than it does over Europe.

The May 10 solar storm rated a top “G5” on the G1 to G5 storm scale, while the “Kp”geomagnetic disturbance index reached Kp8 on the Kp0 (nothing) to Kp9 (OMG!) scale.

I gave a talk at a local community art gallery that evening, and alerted the audience to the likelihood of fine aurora later that night. Sure enough, I got home in time to see the sky already lighting up with aurora in the twilight and behind the clouds.

The clouds cleared off enough to reveal one of the most colourful shows I’d seen in many years. This time there was no question about seeing reds and vivid pinks with the unaided eye. This was the type of show everyone hopes for. But it takes a Kp6 show and higher to spark it.

I blogged previously about the Great May Aurora Display here.

And a music video of the May 10 display incorporating time-lapse and real-time video footage is on my YouTube channel, with the clickable link below. Do enlarge to full screen.

One of the most remarkable aspects of this show was the blue auroras later in the night (shown below), created by sunlight illuminating the upper curtains and reacting with atmospheric nitrogen. The usual auroral greens and reds are from oxygen. Pinks are also from nitrogen. Blues are less common, but were in abundance this night.

Auroras around summer solstice, June 21, can be more colourful and often blue, as the Sun lights the upper atmosphere all night. I saw blue auroras again later in the summer.

July — NLCs and Classic Auroral Arcs

June and July are normally when we in western Canada get good displays of another northern mid-latitude phenomenon, noctilucent clouds (NLCs).

These are ice clouds at 80 km altitude (almost in space) that are lit by sunlight all night long. I saw only a couple of displays of NLCs this year, and it wasn’t for lack of trying and clear nights, even amid forest fire smoke. The panorama above is from home on July 9, over a yellow canola field. NLC season always coincides with peak canola colour time!

Might NLCs be suppressed by high solar activity? There’s some data that suggests they are. However, we weren’t getting many auroras either in early summer.

But at the end of July the Northern Lights returned for some classic shows of arcs across my northern sky, first on July 25 (above), with a prominent sunlit blue/purple ray at left by the Big Dipper. The Kp Index reached Kp5 this night, which is enough to produce a good display from my location in southern Alberta. The Moon is rising at right.

Then again, four nights later on July 29, an auroral arc appeared across the north, this one with reds mixing with greens to create a yellow band in the east, as well as blue and magenta tops to the green arc that follows the curve of the auroral oval.

August 1 — STEVE Appears

While June and July were quiet months, August made up for them.

Of all the auroras this year, only this one, on August 1, produced a showing of STEVE, at least as best I saw in 2024. He can be elusive and easily missed!

STEVE is the odd arc, often white or mauve, that appears southward of the main aurora (from here in the Northern Hemisphere), typically after a show has peaked, then subsided and retreated back north, as it did above.

STEVE stands for Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement, as it is caused by horizontally flowing hot gas, and so is not, by definition, a true aurora created by energetic particles raining vertically down magnetic field lines.

For a classic showing of STEVE see my video, above, from August 2022. High-resolution 4K video I shot this night formed the basis for a scientific research paper, as it revealed structures in STEVE no one had seen before.

STEVEs are often accompanied by green “picket fence fingers” hanging down from the mauve arc. These fingers are more akin to normal auroras, but are created by particles from the STEVE band raining down local magnetic field lines. They do not come from far out in space as they do in a normal aurora!

August 4 — A Coronal Outburst

On the night of August 3/4 I was able to join a photo tour run by local photographer Neil Zeller, to shoot Milky Way nightscapes. Escaping clouds, we ended up at a scenic spot south of Medicine Hat, Alberta, called Red Rock Coulee.

On the way home, the aurora began to let loose behind the clouds. We stopped once off the highway as the aurora brightened in an arc across the northeast, above.

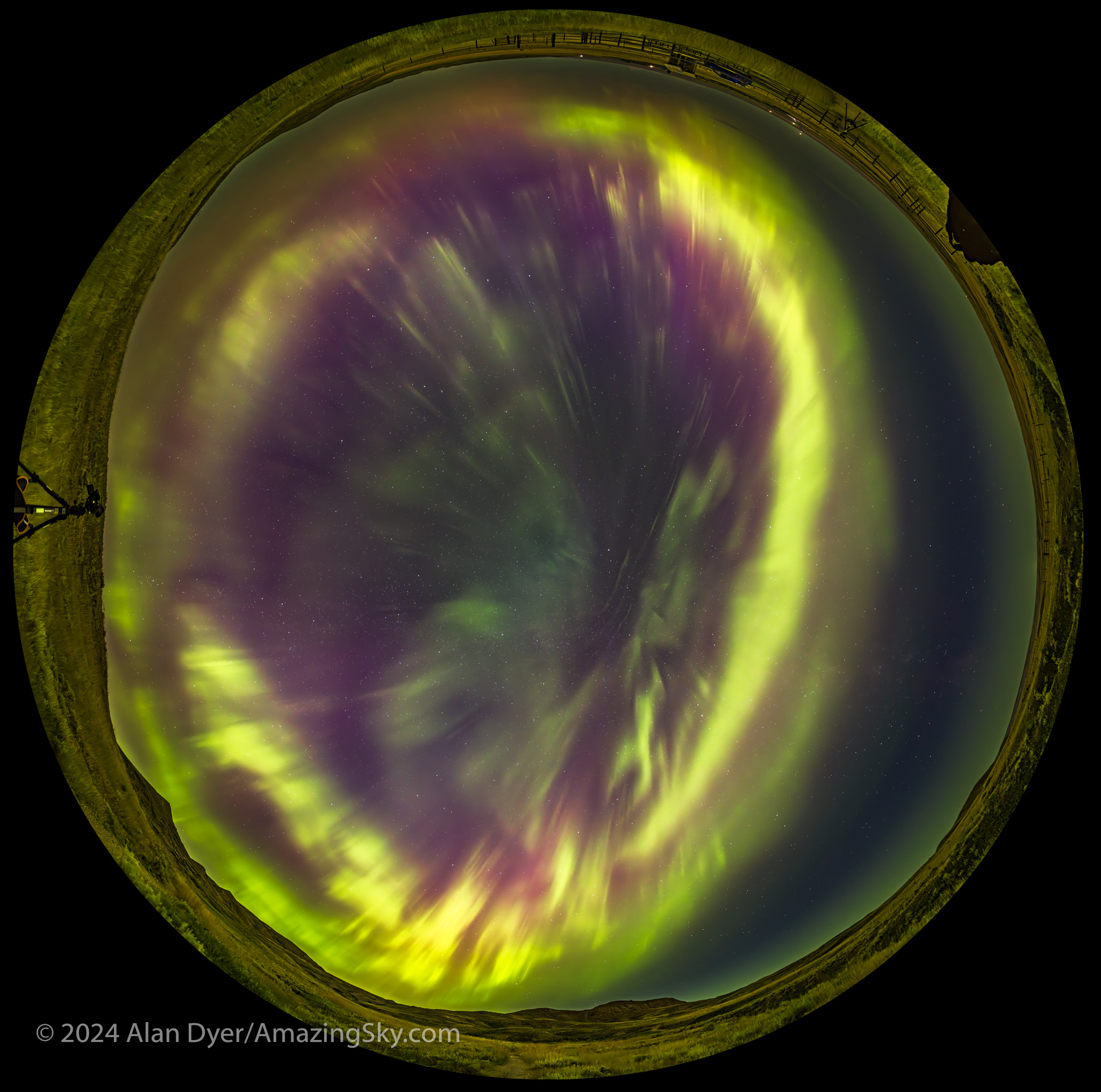

We stopped again later, now at 4 am, and marvelled as the curtains converged at the zenith in the finest manifestation an aurora can produce, a swirling zenith “corona.”

A music video from August 4, using just a single real-time video, not a time-lapse, is above. It shows almost the full but brief appearance of the corona, just as the eye saw it looking straight up!

August 11 — Another Great Display

August was a good month! Right after the annual Saskatchewan Summer Star Party in the Cypress Hills I headed farther east to Grasslands National Park, a favourite dark-sky site I had not visited since 2019.

My plan was to shoot the annual Perseid meteor shower that was to peak on Sunday, August 11, from the same spot I shot it in 2016.

The aurora had other plans. Again, as it did on May 10, the sky was lighting up with colours as it darkened in the evening twilight, above.

The aurora expanded to fill the sky, and with odd fragmented bits, shown above. My trio of cameras set up for the meteor shower got repurposed into taking aurora time-lapses, stills, and panoramas. And selfies! — the title slide for this blog was from this memorable night at Grasslands.

A notable moment was at midnight when, even to the eye, the sky to the east suddenly turned red, and a wave of crimson aurora quickly swept in. The reds from oxygen mix with the more usual auroral greens, also from oxygen, to create areas of yellow in the sky.

A few still frames in the time-lapses did manage to catch a Perseid meteor or two, as above, embedded in the vivid curtains of light. But the meteors were upstaged by the Northern Lights this night.

A music video of this show is above, also on my YouTube channel (it’s been a busy year!). Using only time-lapses, it captures the sudden arrival of the red sub-storm, sped up to be sure, but it seemed that quick!

August 30 — From Onset to Recovery

This night I was hoping to shoot deep-sky objects with telescopes I was testing at home. Again, the aurora had other ideas.

As the movie shows, a band of Lights across the north early in the evening promised to develop. So I set up a time-lapse camera and fisheye lens to capture, for once, a complete development of an aurora, from a diffuse band, to the onset of an active sub-storm outburst which occurred, as they often do, at midnight when we are looking down Earth’s magnetic tail at the source of the aurora particles.

As the video shows, the storm then subsides and the aurora changes character. During the post-sub-storm “recovery phase,” usually when we are under the dawn sector of the auroral oval, an aurora can switch to a pulsating effect with patches of aurora flashing off and on and flaming up to the zenith. This form of aurora is caused by electrons trapped in the Van Allen radiation belts that are bouncing back and forth from pole to pole.

To capture this aspect of the show I switched to real-time video with that same lens, reviewed here on a previous blog.

The music video of this show, above, uses a mix of time-lapses and real-time videos shot with the 360º 7.5mm fisheye lens. It’s a great aurora lens for capturing it all!

September 16 — A Colourful All-Sky Show

Auroras are often most frequent, active, and bright around the spring and autumn equinoxes, when the magnetic field lines of Earth and interplanetary space better connect. It’s called the Russell-McPherron Effect.

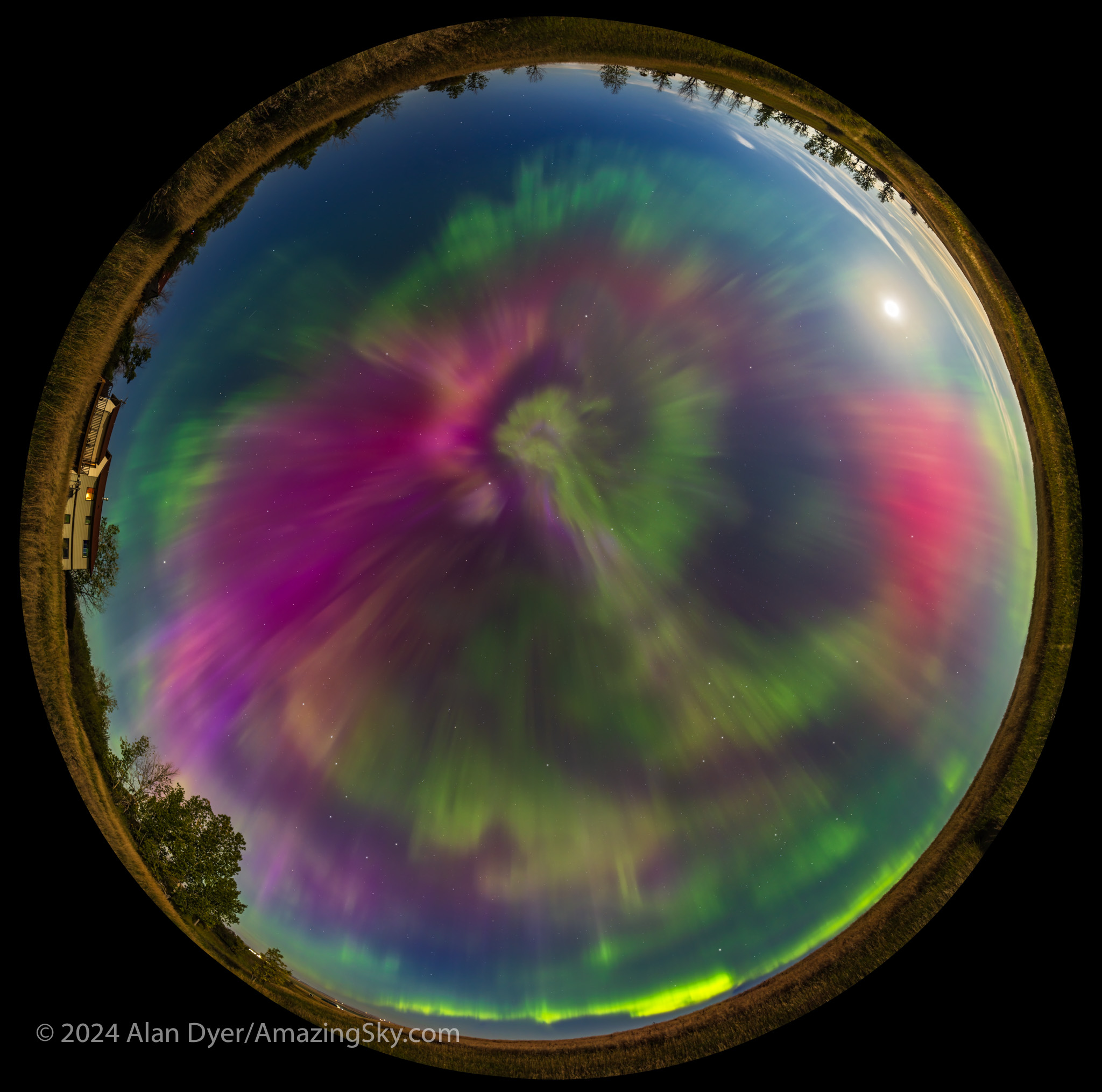

September 16 (6 days before the autumnal equinox) saw another all-sky show that, for us in western Canada, rivalled May 10. As with the spring show, this aurora was notable for its great range of colours, with nitrogen pinks and magentas mixed in with shades of oxygen yellow-greens and reds.

A darker blue-green band to the south (at left above) during the peak could be aurora from incoming protons exciting hydrogen, not from the usual electrons that excite all other auroras and light up oxygen and nitrogen atoms and molecules.

Yes, there are proton auroras. Another research paper using my images from an October 2021 aurora explored the relationship between proton auroras and SAR arcs (explained below).

The September 16 show started with a diffuse band which quickly exploded as a sub-storm onslaught of energetic particles arrived to light up the aurora with greater brilliance, colours, and rapid motion. The onset of a substorm can happen in literally just a minute.

Even the nearly Full Moon failed to diminish this show, seen from home under perfect skies. Luckily, the smoky season had abated.

A music video of this night’s show is also above on YouTube. Do click through to watch this and the other videos in full screen mode.

October 10 — Red Aurora from Arizona

Six months to the day after the great May 10 show, the sky erupted again with auroras seen all over the world, even from more southerly latitudes that don’t normally see Northern Lights.

I know because I was at one of those latitudes, in southern Arizona at 32° N. The aurora created the kind of show seen from areas that don’t normally get auroras — a red sky on the horizon. It is these ominous red skies that provoked Medieval fears of divine wrath and myths of armies clashing in the distant North.

Red auroras can also occur in the Southern Hemisphere (as can every other form of aurora) when the aurora australis brightens and extends farther north than normal, lighting up the southern sky red at locations that rarely see the Southern Lights.

In both cases we are seeing just the red tops of distant curtains that mostly lie hidden over the horizon, the red coming from oxygen reactions that can happen only at the rarefied altitudes of 300 to 500 km. Oxygen greens come from 100 to 300 km up.

From Arizona, I saw what many in the U.S. saw this night — a prominent glow, obviously red even to the eye, across the northern horizon. I was missing a far better show at home!

But unique to my more southerly site was this phenomenon, also widely seen across the U.S. and southern Canada.

Accompanying the “normal” aurora to the north was a diffuse red (to the camera) arc across the sky that lasted most of the night. This was a Stable Auroral Red (SAR) arc, created by thermal energy flowing horizontally in the high atmosphere some 400 km up.

SARs have been seen evolving into STEVEs, as the mechanisms seem related. Indeed, one of my images from August 1, shown above, seems to show a SAR/STEVE hybrid.

I set up a wide-angle lens and time-lapse hoping to catch such an evolution first-hand, which would have been of great interest to researchers. Alas, the SAR did not cooperate, stubbornly remaining a SAR all night.

By dawn, with blue sunlight at work, the SAR looked magenta in the twilight, accompanied by two other sky glows:

- The pyramid-shaped Zodiacal Light created by sunlight reflecting off cometary and meteoric dust in the inner solar system,

- And the winter Milky Way, created by the combined light of distant stars in our section of our Galaxy.

- So in one image we have atmospheric, interplanetary, and interstellar sky glows! This was truly an amazing sky, the likes of which I might never see again.

Ending the Year — November in Norway

In early November I headed to Norway to instruct my first aurora group there since 2019. The location was on board a ship, the m/s Nordkapp, a ferry in the Hurtigruten fleet that does 12-day runs along the coast, from Bergen in the south, to Kirkenes in the far north, and back again.

We got three nights in a row of active auroras on the northbound voyage. A Kp4 to 5 storm brought the Lights farther south and overhead for us early in the voyage, something we don’t normally see in Norway until we get underneath the auroral oval, which at that longitude in the world lies above the Arctic Circle, north of 66° latitude.

But on November 9, with a storm underway, the show started early, rudely interrupting our group’s cocktail hour as we all rushed up on deck. As it can do, the aurora glowing in a twilight sky took on added tints.

The next night, November 10, as we sailed through the mountainous Lofoten Islands, we were treated to an aurora with lots of red content, above. No two auroras are alike!

A curtain of aurora also nicely pointed the way into the short but scenic Trollfjord, a fjord the ship captains like to navigate into for a memorable side trip as we slide through the narrow canyon with seemingly inches to spare.

A gallery of my Norway auroras is here on my website.

All going well, I will be back in Norway for two cruises in October. Join me!

A music video of real-time aurora sequences shot from on deck during my November 2024 Norway cruise is above on YouTube. Note the phones held high, the way most people now shoot the aurora, and usually with very good success!

What’s Coming for 2025?

We have more to look forward to in 2025.

First, it is likely that the Sun has not peaked, but may undergo a second peak of maximum activity in 2025 or 2026. A double peak is common at many solar maxes. Just look at the graph at the opening of the blog, and the previous peaks of Cycles 23 and 24.

Plus, the most energetic solar flares and storms often occur after the peak on the downward trend of activity. So we could well see more worldwide aurora displays like we had on May 10 and October 10 in the coming two to three years. The show is far from over!

Watch websites like SpaceWeather.com for aurora alerts and news of solar events coming our way.

— Alan, December 15, 2024 / AmazingSky.com